3.1 Prescriptions

A prescription is an order of medication for a patient that is issued by a physician or another licensed healthcare prescriber, such as a nurse practitioner or a dentist, for a valid medical condition. Prescriptions are written for patients and are typically relayed from prescribers to pharmacies for dispensing to patients.

Understanding Different Types of Prescriptions

Prescriptions may be received by the pharmacy by several means, including written prescriptions, faxed prescriptions, telephone prescriptions, and e-prescriptions. You need to interpret the prescription to determine the types of calculations that are necessary to fill the order correctly and appropriately. The requirements for information that appears on a prescription are regulated by state law and, therefore, vary among states. However, the following elements appear on every prescription: patient information, prescriber information, and medication information. In addition, controlled-substance prescriptions must follow specific regulations regarding their method of delivery.

Put Down Roots

Put Down Roots

The word prescription comes from the Latin word praescriptus, with the prefix pre– meaning “before” and the root word script meaning “written.” Thus, the word prescription means “to write before,” alluding to the fact that an order must be written down before a medication is prepared.

Written Prescriptions

A written prescription is recorded by a licensed healthcare professional on a preprinted form bearing the name, address, and telephone and fax numbers of the prescriber; information about the patient; the date; and the medication prescribed. A written prescription is typically given to the patient, who then submits the form to a pharmacy for filling.

Work Wise

Work Wise

A written prescription is often referred to as the “hard copy” in community pharmacy settings.

Faxed Prescriptions

A faxed prescription is written by a prescriber and then faxed to the appropriate pharmacy. This order contains the necessary patient demographic, prescriber, and medication information to fill the prescription. Faxed orders are entered into the patient’s medication profile by a pharmacy technician and then verified by a pharmacist.

Telephone Prescriptions

A telephone prescription is phoned into a pharmacy. A telephone order, sometimes called a verbal order, must be transcribed into a written prescription and verified for accuracy prior to being entered into the computerized patient profile. In states allowing pharmacy technicians to receive verbal orders, the order must be checked by a pharmacist prior to computer entry.

E-prescriptions

An electronic prescription (e-prescription) is transmitted electronically from a prescriber to a pharmacy, typically via a personal computer in an examination room or from a handheld device such as a tablet or a smartphone. E-prescriptions have become the most common prescribing method for healthcare practitioners. For prescribers and pharmacy personnel, e-prescriptions streamline the prescription-filling process, improve billing, minimize the potential for prescription forgeries, and reduce medication errors. For patients, e-prescriptions increase accuracy, improve safety, and decrease filling wait times.

This pharmacist is receiving a verbal prescription over the telephone, which will be transcribed into a written prescription.

Controlled-Substance Prescriptions

A controlled-substance prescription must follow specific regulations for delivery. Controlled substances in Schedules III–V can be written, faxed, or communicated verbally. Traditionally, prescriptions for Schedule II controlled substances were primarily delivered as written prescriptions with few exceptions. However, federal law now allows electronic transmission of controlled-substance prescriptions (Schedules II–V). The law stipulates that electronically transmitted prescriptions for controlled substances are valid only if both the prescriber and the pharmacy that fills the prescription use software that is compliant with the security requirements outlined in the Electronic Prescriptions for Controlled Substances (EPCS) program of the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). When such a prescription is transmitted, the pharmacist sees an EPCS logo appear on the computer screen that verifies the validity of the prescription. Some pharmacies and physicians’ offices do not yet have the software required to transmit these prescriptions.

Safety Alert

Safety Alert

Many states now require that written prescriptions for controlled substances be recorded on tamper-resistant prescription pads (TRPPs) to eliminate forgeries. In addition, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services requires that all Medicaid prescriptions be written on TRPPs.

Learning the Components of Prescriptions

As mentioned earlier, the following elements appear on every prescription: patient information, prescriber information, and medication information. You must diligently verify and interpret this prescription information in order to accurately perform calculations, provide patients with the correct quantity of medication, and bill insurance companies appropriately.

Patient Information

Every prescription order must have enough information to uniquely identify a patient. In addition to the patient’s full name (first and last), most states also require an outpatient prescription (a prescription for a patient who is not in a hospital or other medical institution) to include the patient’s address.

A prescription must also contain the patient’s birth date, which is used by the pharmacy to distinguish between patients with the same name and to bill the patient’s insurance provider. Knowing the patient’s age also helps the pharmacist evaluate the appropriateness of the drug, its quantity, and the dosage form prescribed, thus minimizing medication errors.

Many pharmacies require that the patient’s height and weight be available, either on the prescription itself or in the patient’s profile. A patient’s height is generally measured in centimeters (cm) or inches (″ or in.). A patient’s weight may be measured in either kilograms (kg) or pounds (# or lb). If height and weight are included in the patient information, these measurements must include the units because metric units of measurement are quite different from household units of measurement. For example, a 76 cm patient is most likely a child under three years of age, whereas a 76″ patient is a very tall adult; a 100 kg patient is more than twice the size of a 100 lb patient. (To learn more about height and weight conversions, refer to Chapter 4.)

Safety Alert

Safety Alert

To prevent medication errors, pharmacy technicians should always include units of measurement when recording a patient’s height and weight.

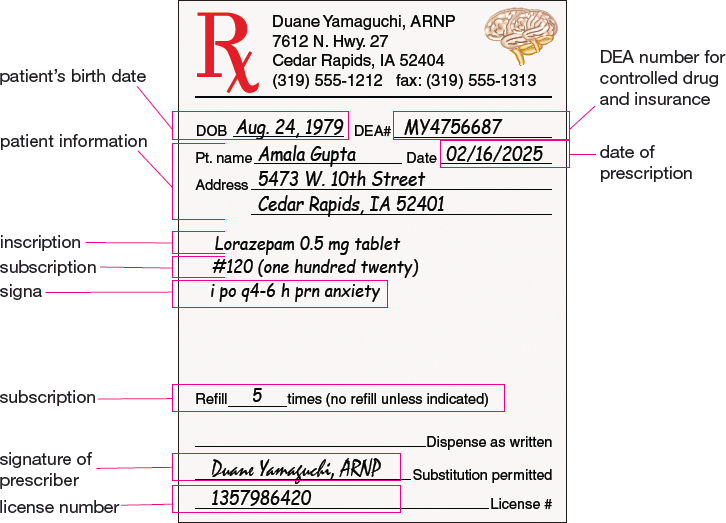

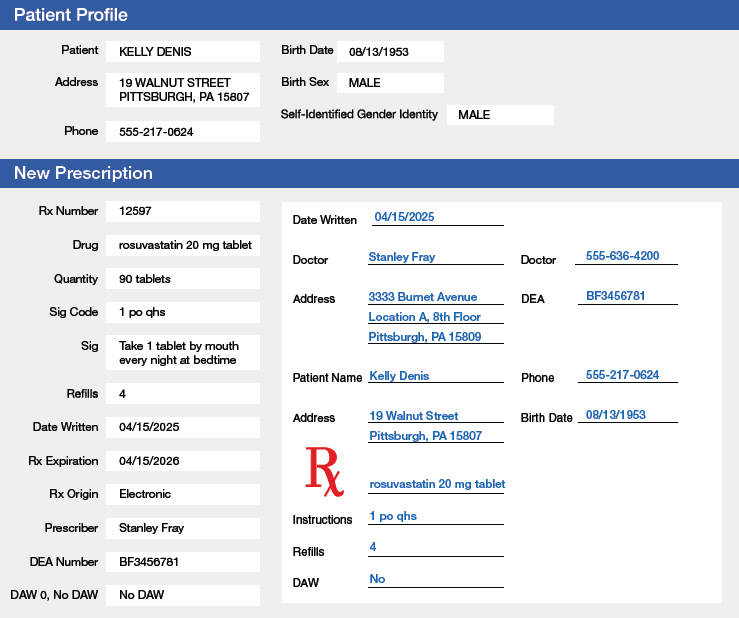

Figures 3.1 and 3.2 illustrate components of a written prescription and an e-prescription. Patient information such as the patient’s name, birth date, and address is included in both examples.

Figure 3.1 Components of a Written Prescription

All prescriptions should be legible, be written in ink (if handwritten), and include a leading zero before any number that is less than one (in this case, 0.5 mg). If appropriate, the prescription should also include the indication (in this case, anxiety).

Figure 3.2 Components of an E-prescription

E-prescriptions are transmitted electronically to pharmacies. This example shows the e-prescription sent from the prescriber to the pharmacy on the right side of the computer screen. The left side of the screen shows how the e-prescription is integrated into the pharmacy’s order entry and dispensing software. Note that the abbreviation mg means “milligrams”; the abbreviation po means “by mouth”; and the abbreviation qhs means “at bedtime.”

Prescriber Information and DEA Numbers

In most states, outpatient prescription orders must include the name, authority (such as medical doctor, doctor of osteopathy, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, dentist, etc.), and address of the prescribing practitioner. Frequently, the prescription order includes the prescriber’s telephone number.

Other prescriber identification information, such as a National Provider Identifier (NPI) number and a US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) number, may also be included on a prescription. An NPI number is a 10-digit, unique identification number for healthcare providers. This number is required by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) for all administrative and financial healthcare transactions. A DEA number is a carefully regulated registration code that signifies the authority of the holder to prescribe or handle controlled substances. Sometimes, the DEA number of the prescriber is handwritten (rather than preprinted) on a paper prescription to prevent forgeries.

Work Wise

Work Wise

If needed, a pharmacy technician can always look up a prescriber’s NPI number on the NPI registry website at https://npiregistry.cms.hhs.gov.

A DEA number is always two letters followed by seven digits. The first two letters of the DEA number provide information about the prescriber:

The first letter in the DEA number usually (but not always) designates the level of authority of the holder. For example, the letters A, B, and F are used for primary-level practitioners such as physicians and dentists, and the letter M is used to indicate mid-level practitioners such as nurse practitioners, nurse midwives, nurse anesthetists, clinical nurse specialists, and physician assistants.

The second letter in the DEA number represents the first letter of the prescriber’s last name at the time of DEA number application. There are instances where the second letter in a DEA number does not match the first letter of the prescriber’s last name. This mismatch occurs most frequently when a prescriber’s last name is legally changed after the DEA number was assigned (for example, in the case of marriage or divorce).

Therefore, the first two letters of the DEA number for a family medicine physician named Dr. Mary Smith might be AS, BS, or FS, whereas the first two letters for a nurse practitioner named David Jones might be MJ.

As mentioned earlier, these first two letters are followed by seven digits. The first six digits are used to calculate a sum known as a checksum (outlined in Table 3.1). The last of the seven digits is called a check digit. The checksum and check digit give pharmacists and pharmacy technicians one way to confirm whether a DEA number is fraudulent. A DEA number that does not have a correct check digit (as determined by the steps in Table 3.1) is invalid. However, be aware that passing the check digit verification process does not necessarily mean that a DEA number is valid. If you discover an invalid DEA number or suspect a problem with the authenticity of a prescription, you must notify a pharmacist immediately.

Table 3.1 DEA Check Digit Verification Process

Step 1. Add the first, third, and fifth digits of the DEA number. Step 2. Add the second, fourth, and sixth digits of the DEA number. Step 3. Double the sum obtained in Step 2 (i.e., multiply it by 2). Step 4. Add the results of Steps 1 and 3. This sum is known as the checksum. The last digit of the checksum should match the check digit, or the last digit of the DEA number. |

The following examples demonstrate how the steps in Table 3.1 can be used to check for fraudulent DEA numbers.

Example 3.1.1

A patient brings a prescription for methylphenidate tablets to the pharmacy. The prescription is signed by Anders Karl Johnson, MD, and bears a DEA number of BJ2345678. Could this be a valid DEA number?

To begin, review the letters of the DEA number. The first letter is consistent with the prescriber’s level of authority (the letters A, B, or F for a primary-level practitioner), and the second letter (the letter J) matches the last name of the physician.

Next, check the validity of the check digit by following the steps outlined in Table 3.1.

Step 1 |

Add the first, third, and fifth digits of the DEA number. 2 + 4 + 6 = 12 |

Step 2 |

Add the second, fourth, and sixth digits of the DEA number. 3 + 5 + 7 = 15 |

Step 3 |

Multiply the sum obtained in Step 2 by 2. 15 × 2 = 30 |

Step 4 |

Add the results of Steps 1 and 3. The last digit of this sum, or the checksum, should match the check digit, the last digit of the DEA number. 12 + 30 = 42 |

Answer: Because the check digit is 8, not 2, this DEA number is invalid.

Example 3.1.2

A patient brings a prescription for oxycodone to the pharmacy. The prescription is signed by nurse practitioner Ann Jefferson and bears a DEA number of MJ3456781. (In the state where the prescription is received, nurse practitioners are authorized to prescribe narcotic analgesics.) Could this be a valid DEA number?

To begin, review the letters of the DEA number. The first letter is consistent with the prescriber’s level of authority (the letter M for a nurse practitioner), and the second letter (the letter J) matches the last name of the prescriber.

Now, check the validity of the check digit.

Step 1 |

Add the first, third, and fifth digits of the DEA number. 3 + 5 + 7 = 15 |

Step 2 |

Add the second, fourth, and sixth digits of the DEA number. 4 + 6 + 8 = 18 |

Step 3 |

Multiply the sum obtained in Step 2 by 2. 18 × 2 = 36 |

Step 4 |

Add the results of Steps 1 and 3. The last digit of this sum, or the checksum, should match the check digit, the last digit of the DEA number. 15 + 36 = 51 |

Answer: Because the check digit is 1, this DEA number could be valid.

The signature of the prescriber must be present on a prescription. For a paper prescription, the signature must be in ink. An electronic signature may be utilized on a faxed prescription for all medications except for controlled substances. E-prescriptions must include an electronic signature.

In many states, a prescriber can use the signature line of a prescription to specify that a pharmacy must dispense the brand-name drug (rather than the less-expensive generic drug). In some states, there are two signature lines at the bottom of a prescription: one stating dispense as written, or DAW, and the other stating substitution permitted. If the dispense as written line is signed, then a pharmacy cannot substitute a generic equivalent when filling the prescription.

Medication Information

The date a prescription is written or ordered must appear on the document. Most prescriptions are valid for one year. Prescriptions for Schedule III and Schedule IV controlled substances are valid for six months. In addition, the date a prescription is written may be important to a pharmacist for therapeutic reasons. For example, if a prescription for an antibiotic was written several weeks ago, a pharmacist may need to determine whether the patient still needs to take the medication.

A prescription order must always designate the medication that is intended for the patient. The inscription is the part of the prescription that lists the medication prescribed, including the dosage form and strength or amount. Sometimes, the drug will be identified by its generic name, the name by which it was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a unique chemical product safe and effective for its approved indication or use. The generic name of a drug is the same, regardless of the company that manufactures it or the dosage form or packaging in which it is supplied. Other times, a prescriber will specify a brand name. The brand name is a registered trademark of the manufacturer and may indicate the dosage form or packaging of the drug as well. For example, Prinivil and Zestril are two brand names under which the generic drug lisinopril is marketed by pharmaceutical companies. Generic drugs are often less expensive than brand-name drugs and are often automatically substituted for brand-name drugs in the pharmacy software under regulations now existing in every state. If a prescription for a brand-name drug is filled with a generic equivalent, then the name, strength, and manufacturer of the generic substitution may be included on the dispensed medication container label. In other situations, the pharmacy must supply the exact brand-name drug prescribed, unless the pharmacist has discussed a substitution with the prescriber.

WORKPLACE WISDOM

WORKPLACE WISDOM

As a pharmacy technician, it is important that you understand how generic drugs and brand-name drugs are similar and how they are different. You may also be asked by patients to explain the distinctions between these two drug products. Generic drugs are required to have the same active ingredient(s), strength, dosage form, and route of administration as brand-name drugs. Generic drug manufacturers must also prove that the efficacy of their medications is equivalent to that of brand-name products. However, the inactive ingredients of generic drugs do not have to be the same as those of brand-name products. A small amount of variability may be present, which is permitted and monitored by the FDA.

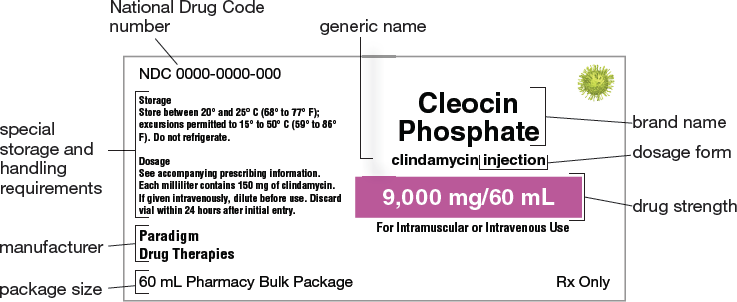

Figure 3.3 identifies the standard parts of a drug label for Cleocin Phosphate. As shown in this example, the label of a brand-name drug indicates both the brand name and the generic name. Medications with a given name (brand or generic) are frequently available in a variety of strengths, doses, or dosage forms, and information about the particular strength, dose, and dosage form is clearly stated on the drug label. Because drugs present a similar array of choices (brand names, strengths, doses, and dosage forms), the proper product to select must be clear in the prescription order.

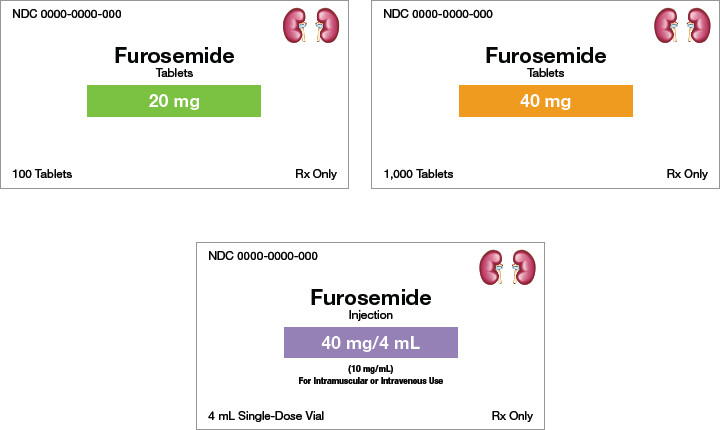

Figure 3.4 shows labels for the drug furosemide in different dosage forms and strengths. Note how the labels use color to help distinguish the unique information.

Figure 3.3 Parts of a Drug Label

Although medication labels from different manufacturers vary slightly in format, the labels’ components remain the same. As a pharmacy technician, you must be able to identify and interpret all parts of a drug label.

Figure 3.4 Comparison of Dosage Forms

These medication labels indicate 20 mg tablets, 40 mg tablets, and a 40 mg/4 mL solution.

Name Exchange

Name Exchange

Furosemide, a diuretic, is the generic name for the brand-name drug Lasix.

The signa (commonly referred to as the “sig”) is the part of the prescription that communicates the directions for use. This information is transferred from the prescription onto the label that is placed on the medication container for patient use.

Put Down Roots

Put Down Roots

The term signa comes from the Latin verb signare, meaning “to mark, write, or indicate.” A prescription’s signa provides instruction for patient use.

The subscription is the part of the prescription that lists the instructions to the pharmacist about dispensing the medication, including quantity to dispense, compounding instructions, labeling instructions, information about the appropriateness of dispensing drug equivalents, and refill information. A refill is an approval by the prescriber to dispense the medication again without requiring a new prescription. If the refill section on the prescription is left blank, the prescription cannot be refilled. The words no refill (sometimes abbreviated NR) will appear on the medication container label, and no refill will be entered into the patient’s profile. Even if the refill blank on the prescription indicates a prn (or “as needed”) order, unlimited duration is not allowed. Most pharmacies and state laws require at least yearly updates on prn (also written PRN) prescriptions.

Quantity to Dispense

Every outpatient prescription order must indicate to the pharmacist what quantity to dispense. Sometimes, as in Figure 3.1, a prescriber writes the number of tablets to dispense next to “#” (used as a number symbol). This number is often written as a Roman numeral or spelled out (“thirty” for #30) on written prescriptions. Using a word rather than a number to indicate the quantity makes it more difficult to obtain a greater quantity than prescribed because a number is easier to alter. Other times, a prescriber indicates the number of doses the patient is to take or the number of days the therapy is to last. The pharmacy staff, in turn, calculates the quantity to dispense from the information on the prescription.

Calculating quantity to dispense can be done using the ratio-proportion method or the dimensional analysis method. The following examples show how to calculate the quantity to dispense utilizing these methods.

Example 3.1.3

A prescription for amoxicillin 125 mg chewable tablets twice daily is written for a patient in your pharmacy. How many chewable tablets should be dispensed for a 10-day supply?

You can solve this problem by using the ratio-proportion method or by using the dimensional analysis method.

Ratio-Proportion Method

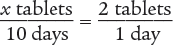

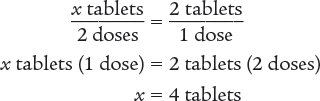

To begin, set up a ratio.

Then use the means–extremes property of proportions to cross multiply.

x tablets (1 day) = 2 tablets (10 days)

x = 20 tablets

Verify your answer by checking that the product of the means equals the product of the extremes.

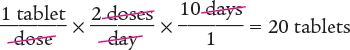

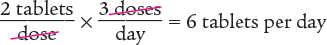

Dimensional Analysis Method

To begin, you know the desired units are tablets. Set up the dimensional analysis calculation with tablets in the numerator. Then cancel out the units dose(s) and day(s).

Answer: The pharmacy should dispense 20 tablets for a 10-day supply.

Example 3.1.4

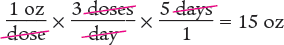

A prescription for an antacid states, “Take 1 oz three times a day,” and instructs the pharmacy to dispense a 5-day supply. What volume should be dispensed?

You can use a multi-step or a one-step dimensional analysis method to solve this problem.

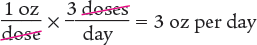

Dimensional Analysis Multi-Step Method

To begin, you know that the patient takes 1 ounce (oz) three times a day. Using that information, determine the number of ounces taken in one day. Note that the units cancel out, as shown below.

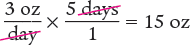

Next, determine the amount to dispense by multiplying the daily dose by the number of days.

Dimensional Analysis One-Step Method

You can also perform these calculations in one step.

Answer: A 15 oz volume should be dispensed for a 5-day supply.

Example 3.1.5

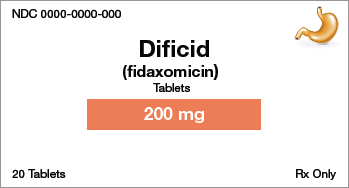

A prescription for Dificid states, “Take 200 mg every 12 hours,” and instructs the pharmacy to dispense a 7-day supply. The pharmacy has the following medication in stock. How many tablets are dispensed?

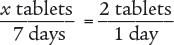

You can solve this problem by using the ratio-proportion method or by using the dimensional analysis method.

Ratio-Proportion Method

To begin, you know that 1 tablet contains 200 mg and that each dose is 200 mg. Therefore, each dose is 1 tablet. You also know that the patient is to take 2 doses per day, which means that the patient takes 2 tablets each day. Use this information to set up a proportion.

Then use the means–extremes property of proportions to cross multiply.

x tablets (1 day) = 2 tablets (7 days)

x = 14 tablets

Verify your answer by checking that the product of the means equals the product of the extremes.

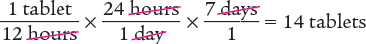

Dimensional Analysis Method

To begin, you know that 1 tablet contains 200 mg and that the patient will take 1 tablet every 12 hours. You also know that there are 24 hours in a day. Therefore, you can determine the number of tablets the patient will need in a 24-hour period (1 day).

Answer: The pharmacy will dispense 14 tablets for a 7-day supply.

When the quantity to dispense has been determined, you will then select the proper dispensing container. Commonly, amber bottles (ovals) are used for liquids and amber vials for tablets or capsules. Amber bottles are often marked with both fluid ounce (fl oz) and milliliter (mL) lines. Common practice uses the metric system, so the quantity indicated on the prescription drug label will usually be indicated in milliliters. When preparing tablets or capsules to fill a prescription, the tablets or capsules are generally counted out by fives, using a specially designed tray and a plastic or metal spatula, and then placed in amber vials.

Amber medication bottles come in many sizes. As a pharmacy technician, you must select the appropriate size to match the dispensed volume.

Days’ Supply

Whether prescriptions are written for a specified number of doses or a specified duration of time, you need to calculate the days’ supply (the number of days that a prescription medication will last a patient when taken as directed). For example, a prescription that is written for a specified number of doses such as #30 and with a dosing schedule of three times daily will last 10 days. Another prescription may be written for a patient to use a medication TID (an abbreviation that means “three times a day”) for 10 days, and the physician has indicated the quantity as QS (an abbreviation that means “a sufficient quantity”). You would calculate that the patient needs 30 doses to complete the therapy prescribed by the physician.

Days’ supply is an important concept in pharmacy practice for two reasons. One reason is that it ensures that the quantity dispensed will meet the needs of the patient according to what the prescriber has indicated. Another reason is that it allows prescription insurance to be billed appropriately. Consider a situation in which you filled a patient’s prescription with an order for a 30 days’ supply of medication and 6 refills. In one instance, imagine that you correctly calculated and entered the days’ supply as 30 and billed the patient’s prescription insurance provider. If the patient took the medication as prescribed and requested a refill after the supply was gone (on day 30), the patient’s prescription insurance provider should accept the refill claim. On the other hand, imagine that you incorrectly calculated the days’ supply as 60 on the first fill and billed the patient’s prescription insurance provider. If the patient took the medication as prescribed and requested a refill after the supply was gone (on day 30), the patient’s prescription insurance provider would deny the refill claim. This denial is because the insurance provider would think that the patient still had more medication (30 additional days), even though the patient truly needed a refill.

To calculate days’ supply, you can use either the ratio-proportion method or the dimensional analysis method. The following examples utilize both these methods.

Name Exchange

Name Exchange

The generic drug ibuprofen is commonly known as Motrin, one of several brand names for this medication.

Example 3.1.6

Calculate the days’ supply for the following prescription.

Ibuprofen 800 mg Tablets

Ibuprofen 800 mg Tablets

Dosing instructions: Take one tablet by mouth two times daily with food.

Quantity to dispense: 60 tablets

You can solve this problem by using the ratio-proportion method or by using the dimensional analysis method.

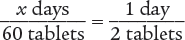

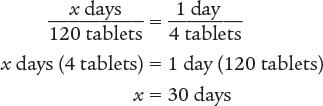

Ratio-Proportion Method

To begin, set up a proportion.

Then use the means–extremes property of proportions to cross multiply.

x days (2 tablets) = 1 day (60 tablets)

x = 30 days

Verify your answer by checking that the product of the means equals the product of the extremes.

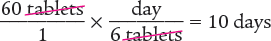

Dimensional Analysis Method

Answer: The days’ supply for this prescription is 30 days.

Example 3.1.7

Calculate the days’ supply for the following prescription.

Ibuprofen 200 mg Tablets

Ibuprofen 200 mg Tablets

Dosing instructions: Take 2 po q8h.

Quantity to dispense: 60 tablets

You can solve this problem by using the ratio-proportion method or by using the dimensional analysis method.

Ratio-Proportion Method

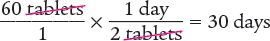

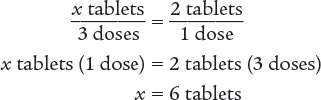

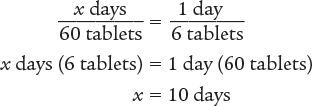

To begin, set up an equivalent proportion to determine the number of tablets that are being taken each day. Using information from this label, you know that the patient is taking a dose every 8 hours. Therefore, the patient is taking 3 doses a day.

Next, set up a proportion to determine the number of days 60 tablets will last.

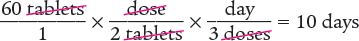

Dimensional Analysis Multi-Step Method

To begin, determine the number of tablets taken each day.

Next, determine the number of days 60 tablets will last.

Dimensional Analysis One-Step Method

Answer: The days’ supply for this prescription is 10 days.

Example 3.1.8

Calculate the days’ supply for the following prescription.

Ibuprofen 200 mg Tablets

Ibuprofen 200 mg Tablets

Dosing instructions: Take 2 po q12h.

Quantity to dispense: 120 tablets

You can solve this problem by using the ratio-proportion method or by using the dimensional analysis method.

Ratio-Proportion Method

To begin, you know that the patient is taking a dose every 12 hours. Therefore, the patient is taking 2 doses a day. Then set up a proportion to determine the number of tablets that are being taken each day. Finally, solve for the unknown variable x.

Next, set up a proportion to determine the number of days 120 tablets will last. Then solve for the unknown variable x.

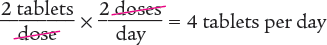

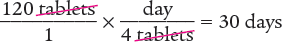

Dimensional Analysis Multi-Step Method

To begin, determine the number of tablets taken each day.

Then determine the number of days 120 tablets will last.

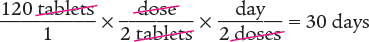

Dimensional Analysis One-Step Method

Answer: The days’ supply for this prescription is 30 days.

Name Exchange

Name Exchange

Acetaminophen/codeine elixir is the generic name for the brand name Tylenol-Codeine Elixir.

3.1 Problem Set

Determine the validity of the following DEA numbers by verifying the prescriber identifiers and using the check digit verification process. Justify your answers.

JC2169870 for James Cardillo, MD

MG3081659 for nurse-midwife Laura Gonzales

BH9998070 for Blanche McKennon, MD

AL6230618 for George Lewis, DO

AD7638224 for Anita Chan, MD

BN4412209 for Srisha Narayana, DO

AK3051492 for Satoru Kudaishi, MD

MS2864228 for clinical nurse specialist Katherine Schultz

BK1179870 for Jess Kolesar, MD

AA2170758 for Sara Alvarez, MD

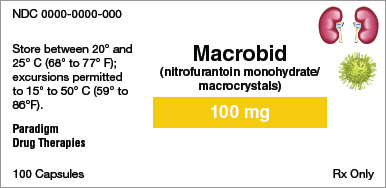

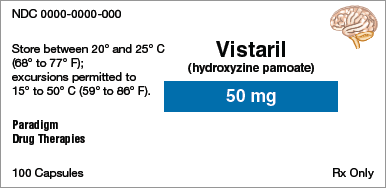

Identify the information indicated for each drug label.

Brand name:

Generic name:

Dosage form:

Strength:

Total quantity:

Storage requirement(s):

Manufacturer:

NDC number:

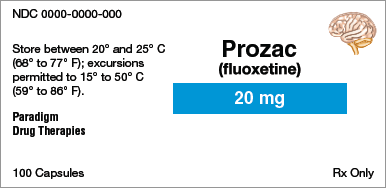

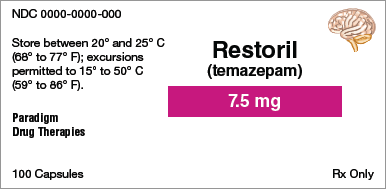

Brand name:

Generic name:

Dosage form:

Strength:

Total quantity:

Storage requirement(s):

Manufacturer:

NDC number:

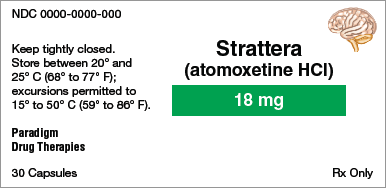

Brand name:

Generic name:

Dosage form:

Strength:

Total quantity:

Storage requirement(s):

Manufacturer:

NDC number:

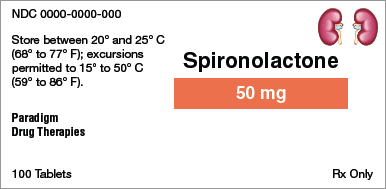

Brand name:

Generic name:

Dosage form:

Strength:

Total quantity:

Storage requirement(s):

Manufacturer:

NDC number:

Brand name:

Generic name:

Dosage form:

Strength:

Total quantity:

Storage requirement(s):

Manufacturer:

NDC number:

Brand name:

Generic name:

Dosage form:

Strength:

Total quantity:

Storage requirement(s):

Manufacturer:

NDC number:

Applications

How much medication should be dispensed for the following prescriptions?

Ibuprofen 400 mg Tablets #XX

Ibuprofen 400 mg Tablets #XXTake one tablet by mouth four times daily with food.

Amoxicillin 500 mg Capsules

Amoxicillin 500 mg CapsulesTake one capsule three times daily for 10 days.

How much medication should be dispensed for the following prescriptions?

Prednisone 5 mg Tablets

Prednisone 5 mg TabletsTake four tablets twice daily for two days;

then three tablets twice daily for two days;

then four tablets once daily for two days;

then three tablets once daily for two days;

then two tablets once daily for two days;

then one tablet once daily for two days.

Milk of Magnesia

Milk of MagnesiaTake one ounce every night at bedtime for one week.

Phenytoin 100 mg Capsules #CL

Phenytoin 100 mg Capsules #CLTake three capsules every morning.

What is the days’ supply for the following prescriptions?

Cephalexin 500 mg Capsules #28

Cephalexin 500 mg Capsules #28Take one capsule by mouth every 12 hours.

Bactrim DS Tablets #90

Bactrim DS Tablets #90Take one tablet by mouth each morning.

Norpace 100 mg Capsules #120

Norpace 100 mg Capsules #120Take one capsule by mouth every 6 hours.

Advair HFA 45/21

Advair HFA 45/21

Dosing instructions: Use one dose (puff) two times daily.

Quantity to dispense: Dispense one inhaler with 120 doses.

Self-check your work in Appendix A.