1.1 The Origins of the Profession

In early civilizations, sickness or disease was often thought to be a form of punishment or a curse by demons or evil spirits. To rid the victims of ill health, relatives would call upon a priest, shaman, or medicinal healer to identify the spiritual cause and then determine the appropriate remedy. At the same time, these civilizations carried with them deep knowledge of medicinal plants and herbal remedies. Early recipes for drug preparations were freely mixed with prayers, chants, incantations, and rituals. Many indigenous healers on every inhabited continent continue these practices, holding great knowledge about medicinal plants in their cultural heritages. Contemporary drug companies are seeking this knowledge for new medications.

Over time, the pharmacy profession evolved into a scientific pursuit involving the compounding and dispensing of medications and drug information. In the wake of this shift from an art to a science, pharmacy has moved from the back rooms of village apothecary shops to a variety of medical practice settings that cater to specific patient populations with medication needs.

Pharmacy practitioners have evolved from ancient medicinal healers and alchemists to educated and trained pharmacists and technicians who rely on quality assurance, safety standards, and technology to ensure the well-being of their patients and customers.

Early Medications and Formularies

The use of drugs in the healing arts by all cultures is as old as human history. Archaeologists exploring the remains of the ancient city-states of Mesopotamia (near present-day Iraq and Iran) unearthed clay tablets listing hundreds of medicinal preparations from various sources, including plants, animals, and minerals. Early inhabitants used the trial-and-error method to compile medicine lists known as pharmacopeias, or dispensatories. Medicine lists are still an important part of pharmacy practice. Current-day drug lists used by insurance carriers and healthcare systems are called drug formularies.

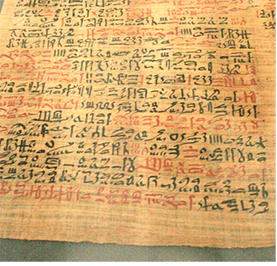

The most famous early formulary was the 110-page Ebers Papyrus (1500 BCE) containing more than 700 prescriptions for ailments that affected early Egyptian cultures.

Eastern Medicine Roots

The use of botanicals as tools of healing became the basis of traditional Eastern medicine, which continues especially in China, Japan, and India. Many of these herbal treatments are widely used in Western cultures today; for example, ginseng is used to enhance energy. A well-known figure who laid the foundation for traditional Eastern medicine is Sushruta.

Put Down Roots

Put Down Roots

The word pharmacy comes from the ancient Greek word pharmakon, meaning “drug or remedy.”

Sushruta was a Hindu surgeon from the sixth century BCE who wrote a medicinal work called the Sushruta Samhita. This work discussed hundreds of surgical procedures, over 1,000 medical conditions, and the medicinal use of over 500 plants. Sushruta’s collection of medicinal recipes is one of the three foundational texts of Indian traditional medicine called Ayurveda. Ayurveda is a holistic approach to medicine that includes a patient’s spiritual well-being. In Ayurvedic medicine, physicians prescribe treatments such as herbs, exercise, and diet and lifestyle changes to maintain a balance of natural forces in the body.

Western medicine moved away from its religious roots into a dependence upon observation, theories and hypotheses, and scientific experimentation.

Greek Roots

Much of contemporary Western medicine and pharmacy practice finds itself indebted to some key early Greek physicians.

Hippocrates Ancient Greeks were the first culture to shift to a more classical scientific approach. The famous Greek physician Hippocrates (ca. 460–370 BCE) believed that illness had a physical explanation and was not the result of possession by evil spirits or disfavor with the gods. He thought that the body’s four “humors,” or liquid systems, (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile) must be in the correct balance to maintain optimal health. His hypothesis formed the origins of the theory of bodily systems and scientific observation practiced today.

During his lifetime, Hippocrates published more than 70 medical texts that scientifically categorized diseases, their signs and symptoms, and their treatments. He is also credited with establishing a lexicon for medical terminology that healthcare professionals still use. Because of his many contributions to the practice of Western medicine, Hippocrates is known as the “Father of Modern Medicine.” He is also known for the Hippocratic Oath—the “do no harm” vow taken by medical practitioners to uphold the highest standards of medical ethics.

Pharm Fact

Pharm Fact

Dioscorides cataloged more than 1,000 substances—mainly botanicals—that had medicinal value.

Dioscorides Another early Greek physician, Pedanius Dioscorides (40–90 CE), is credited with writing one of the world’s greatest pharmaceutical texts: De Materia Medica (On Medical Matters). Written in the first century CE, Dioscorides’s text includes descriptions of herbal remedies and their usage, side effects, quantities, dosages, and storage guidelines. Dioscorides gathered his knowledge of medicinal herbs and minerals as a soldier serving in the Roman army.

As he traveled across the European continent, he collected samples of herbs that he later studied and tested for potential medicinal properties. For 15 centuries, De Materia Medica served as the standard reference for drugs; it is considered the forerunner of current pharmacological references, such as the US Pharmacopeia—National Formulary (USP-NF) and the Prescribers’ Digital Reference.

Galen is considered the “Father of Pharmacy” for extracting, identifying, and classifying active ingredients from natural sources.

Galen Like Dioscorides, Claudius Galen (130–216 CE) was a notable Greek physician. He pioneered the practice of dissecting animals to study organs and anatomy, and he extracted active healing ingredients from plants, analyzing and organizing their medicinal effects on the body. His work led to the coining of the term galenical pharmacy—the extraction of active ingredients into compounding substances, such as juices, saps, and oils.

Work Wise

Work Wise

Prayers and medicine remain linked for many individuals, religions, and cultures; respect and sensitivity are always needed. Some scientific studies associate prayer with health benefits.

From these, Galen created recipes for medicines like ointments and drops. For his extensive body of work and writings in the pharmaceutical sciences, including De Methodo Medendi (On the Healing Method), Galen is considered to be the “Father of Pharmacy.”

Arabic Medicine Roots

Arab civilizations drew upon their own cultural knowledge and that of the Greeks. The Arabic Muslim communities were among the first cultures to develop a list of drugs with dosage formulations for tablets, syrups, and extracts, and to regulate the state-run pharmacies for care of patients.

The twin brothers Cosmas and Damian (approximately 270–303 CE) are symbolic links between the Arab and Greek worlds of medicine and pharmacy. The brothers were Arab Christians living in Syria under Roman rule. They practiced healing and medicine (both surgery and pharmacy) for no charge because they wanted to heal and serve even the poorest patients. They were beheaded by the Romans for being Christians and came to be revered as patron saints of medicine and pharmacy throughout the Middle East and Europe.

The Middle Ages: Ethics and Institutions

During the Middle Ages (approximately 500 to 1400 CE), the profession of pharmacy in both the European and Persian empires was evolving with deep ethical roots of healing service. From the late 700s CE on, the Islamic governments in Egypt and Jerusalem established hospitals to care for the sick. The great Al-Mansur Hospital in Cairo in the 1200s served the rich and poor and had separate wings for different kinds of surgery and care. It also trained both men and women to care for the sick. Caring for the poor is an ongoing concern today for pharmacists and pharmacy technicians, who help those on limited means find ways to afford their medications.

In Europe, since there were no healthcare systems or printing presses, Christian monasteries became storehouses of knowledge as the monks studied and copied manuscripts. Monasteries of monks and abbeys of nuns used the accumulated knowledge of healing to serve the community in many ways. They grew gardens of herbs for food and medicine. These hospitable monastic facilities provided free medicines and healthcare, thus serving as additional precursors to today’s charity hospitals, community healthcare clinics, and public health departments.

As the poor had no access to physicians or even apothecaries, religious orders of monks and nuns invited the poor into their monasteries or guesthouses for healing and care. The assisting novices were early hospital technicians.

A number of Jewish-Arab physicians had a significant impact on the progress of pharmacy practice and ethics in Northern Africa. Moses ben Maimon (Maimonides, 1135–1204 CE), who served the sultan in Cairo, gathered vast amounts of accumulated knowledge into books. He wrote about common illnesses and focused on moderation, healthy living, and illness prevention. Maimon emphasized a sense of humble servitude toward the poor and rich. His prayer to accomplish this was passed on to pharmacy professionals for centuries, even being used in their graduation ceremonies in the United States in the early 20th century. His prayer, other spiritual practices, and the Hippocratic medical oath underpin the contemporary emphasis on professional ethics in pharmacy and medicine.

Put Down Roots

Put Down Roots

Drug is related to the 14th-century Dutch words droge waere, which translates as “dry goods” and came to mean “dried herbs and spices.”

Apothecary is derived from the Latin word apotheca, a storage place associated with dry goods, herbs, and wine.

The Pharmacy Shop

In Western Europe by the 11th and 12th centuries, physicians were often their own pharmacists or chemists and they owned the dispensary that distributed drugs to patients. Pharmacies were commonly under the authority of the College of Physicians or a similar professional group of doctors who followed the traditions of Greek, Roman, and Arab medical practices. However, in 1241, Sicily enforced the Edict of Salerno that forbade physicians from running pharmacists’ shops and required medications to be produced by a qualified chemist in a registered shop. This pioneering concept took a long time to become standard practice.

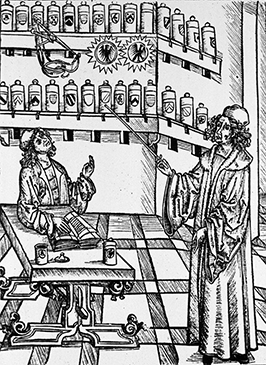

This woodcut of an early pharmacy technician, who was an apprentice for a master chemist, is from A Pharmaceutical Lesson by Hieronymus Brunschwig.

Since only the upper class could afford to consult with a physician, most “common folk” turned to midwives who gathered medicinal plants from the fields, or to wine and spice shopkeepers who also sold herbal medicines from plants and substances from more distant places. An apothecary store concept was developing. The cheapest remedies it stored and sold came from the herbs or plants growing in the surrounding countryside, such as foxglove (Digitalis purpurea) for heart problems.

Most apothecaries had a back room that resembled a small chemistry laboratory where the store chemists could experiment with and compound various formulations. Leeches were also collected and used in bloodletting in an effort to draw out the illness in the blood and balance the bodily fluids. Leeches are still used to keep blood flowing to a wound to help with the healing process. Toxic minerals and noxious tasting plants were used in purging compounds.

The First Guilds

Trade guilds (a cross between a trade union and a professional organization) developed in Europe with a system of apprentices in training to join each profession. The chemist and apothecary apprentices were the early pharmacy technicians. For centuries, English apothecaries belonged to the Grocers Guild. Interestingly, many pharmacies today are located in large grocery and mega-stores.

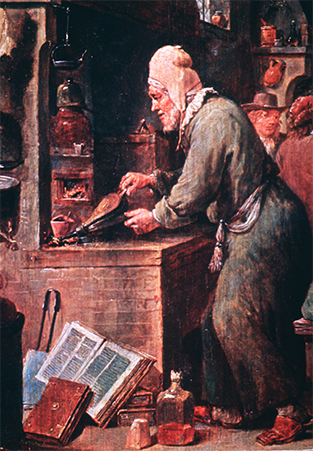

This painting, called The Alchemist, is by David Teniers the Younger (1582–1649) and is displayed at the Prado Museum in Madrid. Alchemists often depended upon assistants.

The Renaissance Alchemy and Apothecary Guilds

Greek, Roman, and Arab scientific influences were less emphasized in Europe during the Renaissance (about 1350–1650 CE). This period saw the rise of pharmacists moving into alchemy, which combined chemistry, metallurgy, physics, and medicine with elements of astrology and mysticism. The alchemists’ goals were to find the most valuable essences to turn something ordinary into something with supernatural or supervaluable properties. For instance, alchemists would attempt to change base metals—such as iron, nickel, or lead—into silver or gold and seek medicinal elixirs or minerals as keys to undying youth.

By 1617 in Britain, the apothecaries had split from the Grocers Guild and joined with the doctors working as medicinal compounders to start their own more specialized guild. This new apothecary guild set standards, determined membership in the profession, and oversaw the training and length of apprenticeships. (The first London apothecary guild was called the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries.) Formalized universities and educational programs in chemistry and medical sciences grew out of these early guild efforts. The state boards of pharmacy and professional pharmacy associations of today (discussed later in the chapter) are considered the offspring of these medieval pharmacy guilds.

The Scientific Revolution and Exploration

In the 17th century, scientific methods were once again emphasized. University students in Western Europe studied the Greek and Latin classics. Scholars pursued and published scientific research, advancing medicine, and pharmacy. It is not surprising that these scholars and researchers borrowed words or word parts from the ancient languages for their new discoveries. Their lexicon—based on Greek and Latin root words, prefixes, and suffixes—remains at the heart of many medical terms today.

As European explorers brought back exotic plants and spices, the list of medicinal agents used in Europe grew. Medicinal practitioners and chemists needed to be skilled not only in biology and chemistry, but also in botany as they created new medicinal agents from these newly introduced natural substances. Rudimentary research to determine the efficacy of these new botanical drugs was initiated.

In North America during the early period of colonization (early 1600s to late 1700s), herbal medicine was widely practiced by Native Americans, and the newcomers learned medicinal uses of the local plants from them. Herbs such as purple coneflower (used to prevent infection), wild ginger (used to treat a stomachache), and saw palmetto (used to treat prostate problems) were common natural remedies. These herbs, along with herbal remedies from the world at large, continue to be sought-after cures, especially as more individuals embrace the practice of holistic and natural medicine.

Among the early colonists in what is now the United States and Canada, there were very few pharmacists. Predictably, the medical profession in settler colonies followed the European model, albeit at a much slower pace. Gradually the profession of medicine separated from that of pharmacy, and the apothecary shop became an independent entity owned and operated by the pharmacist.

Extracts from the Echinacea plant (purple coneflower) are still used today to build immunity and prevent infection.

Early Pharmaceutical Manufacturing and the Need for Standards

By the 1800s, the pharmacist, or chemist, was becoming increasingly recognized as a specialized provider of healthcare in Europe and North America. Physicians had begun to refer patients to the chemists to get their prescribed drug recipes compounded. Chemists relied on their own knowledge and experiences to formulate liquids and powders and to make their own capsules and tablets. Subsequently, they would package and label the drugs in containers and then dispense these medications to patients. For common illnesses, patients went to the chemist for common cures, just as we go to the drug store for over-the-counter (OTC) drugs.

Every physician or pharmacist had favorite formulas or recipes for compounding their medicinal products, though many recipes were similar. Concerned by these varying recipes, a group of eleven physicians convened in 1820 in Washington, DC, to list the standard compounding recipes for the common drugs used in the United States. They called the list the US Pharmacopeia (USP).

Updates of this early drug formulary are now released annually (US Pharmacopeia-National Formulary [USP-NF]), written by the organization that grew out of this meeting. It is now an independent, nonprofit organization called the US Pharmacopeial Convention (USP) that sets quality standards for prescription medications, over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, homeopathic drugs, and dietary supplements. The USP also sets the quality standards for the compounding of both nonsterile, sterile, and hazardous medications; these standards are now widely recognized by the US government and accreditation organizations.

This image is of a German apothecary preserved at the German Pharmacy Museum in Heidelberg Castle.

The First American Pharmacy Schools and Associations

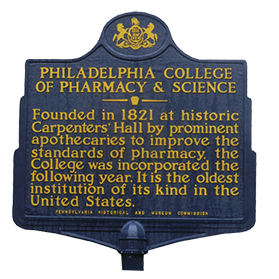

Though Europe had schools for pharmacy, the United States had none. In 1822, two years after the formation of the USP, the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy became the first school in the young nation to offer courses in the pharmaceutical sciences and to grant pharmacy-specific diplomas. Up until this time, no formal schooling was required; one simply became a pharmacist after completing an apprenticeship in an apothecary. (Apprenticeships were the common method for learning a trade at this time.)

In 1852, the American Pharmaceutical Association, now known as the American Pharmacists Association (APhA), was organized to help establish professional practice standards and address the problem of varying qualities and recipes of imported drugs. The APhA called for standards for drug ingredients, compounding, and dosages, and encouraged state governments to regulate the pharmacy profession by requiring pharmacy apprentices to pass formal certification examinations to obtain licensure to practice as pharmacists.

Additional universities worldwide began to offer formal education and degree programs in pharmacy, most focusing on the study of pharmacognosy (the study of the medicinal functions of natural products and chemicals of animal, plant, and mineral origins). Pharmacists in training still spent time as apprentices in apothecaries.

By the late 1800s, large-scale pharmaceutical manufacturing had begun, especially in Europe where universities often worked with manufacturers to have their new laboratory compounds developed and produced. Although many pharmacists continued to rely on herbal extracts as ingredients in their compounded preparations, they began slowly to sell mass-manufactured, artificial chemical preparations as well. For example, in 1899, the German pharmaceutical manufacturer Bayer synthesized aspirin from acetylsalicylic acid and mass-produced it instead of extracting and compounding the salicylic acid from willow-tree bark. Aspirin is still popular today, not only as a remedy for headache, pain, and inflammation, but also as a medication to reduce blood clots in high-risk heart patients.

Compounding Commercial Success Stories

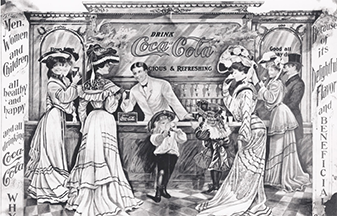

For much of the 19th and 20th centuries in the United States, it was common to find pharmacy soda fountains. Pharmacists added fruit-flavored syrups to carbonated water, and some even concocted recipes or formulations for refreshing new beverages to attract customers. For example, in 1886, John Pemberton, a pharmacist in Atlanta, Georgia, began to sell a compounded tonic called Coca-Cola, which obviously became wildly popular. Its name was derived from one of its ingredients: cocaine. For more than two decades, the Coca-Cola formula contained this plant alkaloid until growing concerns over the harmful and addictive effects of cocaine forced its manufacturer to replace it with caffeine.

While men socialized in bars, women and children went to drug stores and ice cream parlors for refreshments. During Prohibition, almost every drug store had a soda fountain selling drinks, such as Coca-Cola and Pepsi-Cola, which technicians often served.

In 1893, another pharmacist, Caleb Bradham in North Carolina, created a similar carbonated drink later called Pepsi-Cola. Technicians would assist in making the drinks as the soda “jerks,” or servers. The carbonated drinks mass-produced today had their origins at the corner drug store soda fountains. Though the soda fountains faded away in the 1960s with the rise of bottled and canned drinks, these pharmacist-created fountain drinks remain mainstays globally.