7.3 Overview of Prescription Processing

Most people go to a community pharmacy to fill, refill, or pick up a prescription. A prescription (script for short) is defined as a patient medication order issued by a legally authorized physician or a qualified licensed practitioner for a valid medical condition to be filled by authorized pharmacy personnel. On prescription drug labels and packaging there is the recognizable “Rx only” designation, which means that the product cannot be sold without a prescription.

Before filling the prescription, the technician should scan the stock bottle to ensure that the correct drug with the proper NDC number has been selected from the inventory.

Processing a prescription is a complex procedure, with many skills being gained only through experience. No matter what type of prescription is ordered, it follows a similar critical path as described below. However, some prescriptions require additional elements or documentation. For instance, high-cost medications or drugs not on a patient’s insurance formulary require prior authorization (PA), or documented approval, from a prescriber (which will be described in Chapter 8). Dispensing controlled substances and drugs that require a specific risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) also entail special safety steps and documentation. For instance, unique patient education processes must accompany the dispensing of fentanyl (Actiq), an immediate-release narcotic for severe pain, and dofetilide (Tikosyn) for irregular heartbeats. Buprenorphine hydrochloride (Subutex) for opioid dependence also has a REMS to follow. These will be addressed in Chapter 14.

In all situations, the filling process must be accurate and efficient, which requires teamwork and communication between the pharmacy technician and the pharmacist. Each step will be explained in some depth.

Put Down Roots

Put Down Roots

Some think that Rx comes from an abbreviation of the Latin command recipere, which means “take.” Many recipe directions started with “Take this [ingredient]…” The R in recipe may have been combined with part of the Egyptian Eye of Horus, a symbol of good health and power.

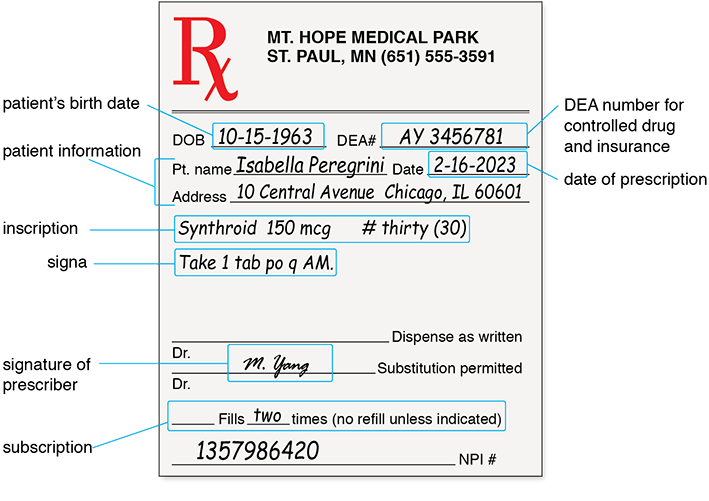

The Prescription Components

All prescriptions must include the same information, so you must be familiar with the basic components. Rx is the official symbol of a prescription. After the pharmacy technician checks that each prescription is complete and accurate—whether on computer, handwritten, or via phone or fax—then the pharmacist double-checks the technician’s work. Each Rx must have the components listed in Table 7.2.

Table 7.2 Parts of a Prescription

Part |

Description |

|---|---|

Prescriber’s information |

Name, address, telephone number, and other information identifying the prescriber; NPI and DEA numbers; and, sometimes, the state license number |

Date |

Date on which the prescription was written; this date may differ from the date on which the prescription was received |

Patient’s information |

Full name, address, telephone number, and date of birth of the patient |

℞ |

Symbol ℞, from the Latin verb recipere meaning “to take” |

Inscription |

Medication prescribed, including generic or brand name, strength, and amount |

Subscription |

Instructions to the pharmacist on dispensing the medication |

Signa |

Directions for the patient to follow (commonly called the sig) |

Additional instructions |

Any additional instructions that the prescriber deems necessary |

Signature |

Signature of the prescriber |

Prescriber’s Information

Prescriber Contact Information The name, address, telephone, and fax number are required for verification on all controlled substances and in case of follow-up questions.

Prescriber’s DEA Number The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) issues a number authorizing a prescriber to be able to medically order controlled substances. The DEA number is essential on all prescriptions for controlled substances. In some states, it functions as an ID number to identify the prescriber. For security reasons and to prevent forgeries, the DEA number of the prescribing physician may not be preprinted on the prescription form but must be specifically written or entered in. Most pharmacies have a database containing local prescribers’ DEA numbers. A formula can be used to check the accuracy of DEA numbers. This information is found in Chapter 14.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

The NPI number may be identified online at the website of the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System (NPPES) at https://PharmPractice7e.ParadigmEducation.com/NPPES.

National Provider Identifier Number The National Provider Identifier (NPI) is necessary for each healthcare provider to get reimbursed for services provided (though not essential for the prescription to be filled). Physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, dentists, and pharmacists are all eligible for an NPI. The NPI number does not replace the DEA number or state license number.

State License Number Some states also require prescribers to include this. Know your state’s rules.

Patient’s Information

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

The terms sex and gender are not interchangeable. Sex is defined as the classification of people as male, female, or intersex based on physical anatomy at birth. Gender identity is defined as one’s internal sense of being male or female. For many people, their sex and gender identity are the same. For others, their sex and gender identity are not the same.

Patient’s Name This should be given in full, including first and last names. Initials alone are not acceptable. If the writing is illegible on a paper form, the technician should verify the spelling of the patient’s name and rewrite it in full above the name on the prescription.

Patient’s Birth Date and Sex This additional identifying information is often required for third-party insurance billing and for correct identification with patients of the same name. Preprinted prescriptions often contain spaces for the birth date. If this space is not filled in, then the technician must request it from the patient or person presenting the prescription. Knowing the patient’s age and sex (many names can be male or female) helps the pharmacist evaluate the appropriateness of the drug, its quantity, and the dosage form prescribed, thus minimizing medication errors.

Patient’s Address, Telephone Number(s) A home and/or cell phone number is/are needed for patient records. An email address is also preferred but optional. A home address is important for billing and insurance purposes. Requesting this information aids patient identification and minimizes dispensing errors. Asking for a secondary phone number (cell or business) assists in following up with patients. For controlled substances, federal law requires a verifiable physical address (not a post office box).

Medication Information

Date the Physician Wrote the Prescription For controlled drugs, the date must be present to have the prescription filled. If no date is included online or written on the prescription, then the technician should call the provider to verify the date. If the undated prescription is for an antibiotic, then the pharmacist should verify with the physician that the patient is still under his or her current care and find out when the antibiotic was issued. The antibiotic may no longer be necessary and, in fact, could be harmful.

Reviewing a prescription for completeness and accuracy in whatever form it is delivered is essential.

Inscription The medication’s name (brand or generic), strength, and amount are listed in the inscription. A drug may be marketed under various brand and generic forms. Most times, the bioequivalent generic drugs are automatically substituted for the brands by the pharmacy software unless the brand is specified as necessary by the prescriber (see “Subscription” below). If the prescription is filled with a generic equivalent, then the name, strength, and manufacturer of the generic drug will be printed on the dispensed medication container label—so remember, the label will not always exactly match the original prescription. That is why a technician needs to know the generic substitutions of the most common brand name drugs prescribed, as discussed in Chapter 4.

Signa A signa (sig) is the prescriber’s directions about how a prescription should be taken or used. This information is transferred from the prescription by the pharmacist or technician into the pharmacy software’s patient profile, which prints it onto the medication container label for patient use. Technicians need to spend time checking the many abbreviations used in the signa—which will be covered in a section to follow. (For a full list of signa abbreviations, see Appendix A.)

Put Down Roots

Put Down Roots

PRN comes from the Latin pro re nata, meaning “for the occasion of need.”

Subscription The subscription is the part that lists the prescriber’s instructions to the pharmacist about filling the inscribed medication, including refill information, compounding and labeling instructions, and notes about dispensing drug equivalents. The prescriber may note dispense as written (DAW) or “brand name medically necessary,” which is sometimes shortened to “brand necessary,” if a prescriber wishes that only the inscribed brand name product be dispensed. This is entered into the computer and billed to insurance as DAW1, required by provider. At times, a patient may request a brand name to be dispensed in lieu of a generic drug, abbreviated as DAW2. When billed to insurance, DAW2 often results in an increase in patient copayment, as noted in earlier chapters.

The prescriber fills in a number (or circles one on a preprinted form) to delineate how often the medication can be filled without requiring a new order. If left blank, then the prescription cannot be refilled. The words no refill (or NR) will appear on the medication container label, and no refill or no refills will be entered into the patient’s computer record. If the prescription indicates as needed, or prn (or p.r.n.), then it can be filled up to a limited number of times, as set by state or federal laws. Most pharmacies and state laws require at least yearly updates on prn, or as needed, prescriptions.

Prescriber’s Signature The prescriber’s signature must appear online as an electronic signature or at the bottom of the paper prescription form in ink. It should be legible and recognizable by both the pharmacy technician and the pharmacist to detect possible forged prescriptions. Signatures by rubber stamps or by nurses and other office personnel are not valid. Faxed prescriptions must also be hand-signed before transmission. E-prescriptions must all be sent through a pharmacy security system approved by the state board of pharmacy. A phoned-in new prescription can come from the provider or provider’s assistant—unless it is a C-II (Schedule II) drug. In some states, two blank signature lines are required at the bottom of the preprinted paper prescription: one next to dispense as written and the other next to the substitution permitted. If the former line is signed, the substitution of a generic equivalent is not permitted (see Figure 7.1). Other states require only one signature line—then brand-necessary directions must be specifically written out as part of the subscription.

If there are any doubts about the authenticity or completeness of a prescription, the pharmacy technician should alert the pharmacist immediately. A telephone call from the pharmacy technician or the pharmacist to the prescriber’s office might be necessary to clarify an order. The technician may be allowed to clarify a prescription in some states, but all changes must be documented on the prescription (and/or in the patient profile). The changes must be accompanied by the name of the provider representative who clarified the issues, the date, and the initials of the technician and pharmacist who made the changes.

Figure 7.1 A Complete Prescription

Table 7.3 The Critical Path of a New Prescription

|

|

Processing Time Expectations

The prescription filling process, which begins with the receipt and review of the prescription and ends with the dispensing to the patient, ideally takes about 5 to 10 minutes per prescription—without interruptions, such as phone calls, other patients dropping off prescriptions, insurance issues, questions to the pharmacist, and so on. Most likely, though, there will be many interruptions during a pharmacy shift, so at times it may take 15 to 20 minutes or more to process a prescription. If there are insurance issues (see Chapter 8), a longer time delay can be expected.