7.4 Computer Communications and Efficiencies

To process prescriptions and accomplish the other pharmacy functions, almost all community pharmacies are now equipped with a specially designed pharmacy software and database management system (DBMS). It is a pharmacy-oriented computerized information system that integrates and interfaces (communicates) with the many different software programs needed for pharmacy operations and online transmissions and networking.

Pharmacy Software Interoperability

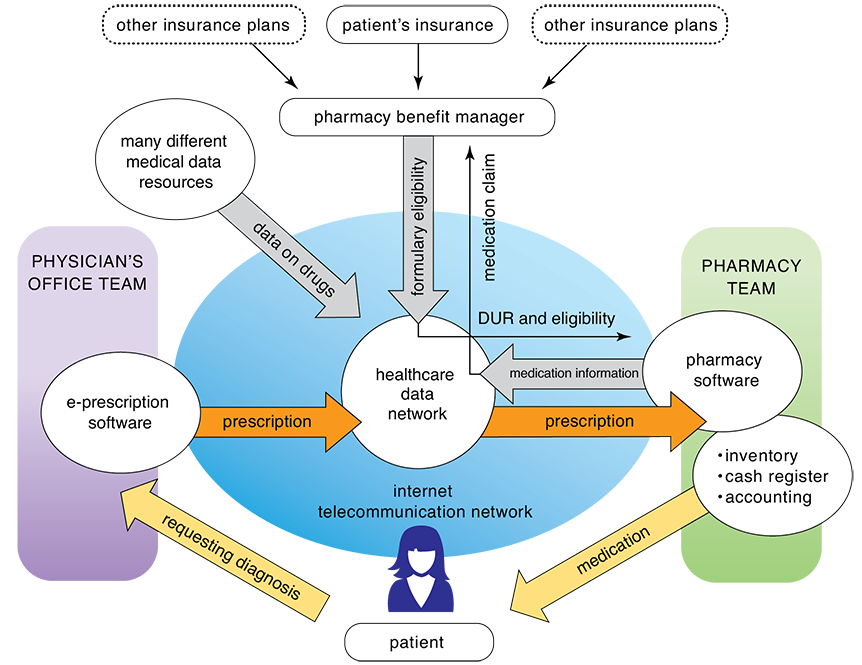

The ability to exchange and process information between various internal and external databases, software, and technology is called interoperability, and it creates the possibility of working together between different pharmacy functions and out-of-pharmacy stakeholders (like the prescriber and insurance representatives) for the best care of the patient. It also provides the most economical and time-efficient community pharmacy practices. Prescribers also depend upon interoperability within their clinics and hospital networks for medical information and to transmit e-prescriptions. (see Figure 7.2).

A technician must carefully input the hard copy prescription and insurance information into the patient’s computer profile to begin the internal and online processing through the pharmacy’s interfacing DBMS.

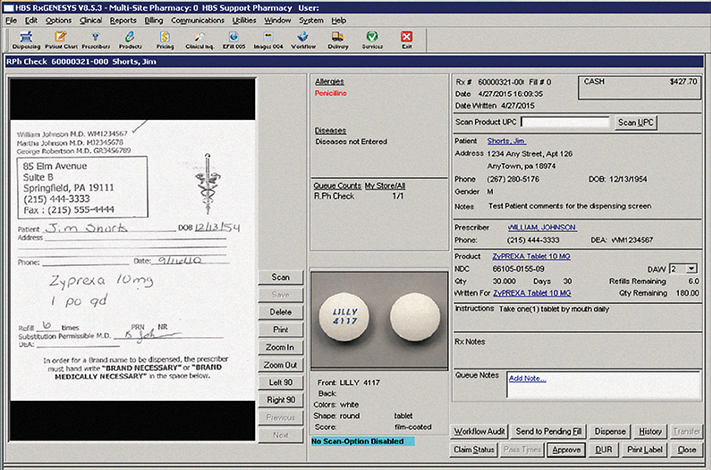

Figure 7.2 Interoperability and E-Prescription Flow

Usually the DBMS software is menu-driven or Windows-based, allowing the technician to choose fields or functions easily from a menu of options on the screen by typing a single keystroke or function key on the keyboard. The pharmacy database typically contains the patient profile, physician database, pharmacy drug inventory, and a directory of prescribers and insurance plans. The software usually allows the technician to scan a written prescription and enter new prescription information or retrieve refill information. The fields of information can be sorted or queried to the patient’s name, address, phone number, and date of birth; the prescription’s number, drug name, National Drug Code (NDC) number, dosage and quantity of the drug, and number of refills; and the prescriber’s name, address, phone number, and DEA number. As part of the drug utilization review (DUR), the systems provide automatic warnings about possible allergic or other adverse reactions. Some software applications even provide a picture or description of the medication to avoid errors.

Most of these pharmacy database systems also are capable of tracking expenses and inventory reports, generating reports concerning controlled substances or patient insurance, performing special dosing calculations, and retrieving medical and pharmacy literature. (More will be presented on the pharmacy DBMS and online insurance processing in Chapter 8 and overall pharmacy informatics, or information systems, in Chapter 10.)

Some examples of pharmacy software management systems include Rx30 Pharmacy System, SRS Pharmacy Systems, Epic’s NCPDP Script Interface, and Prodigy’s PROscript 2000. Some interface with bar code scanning technology and other automation, billing, retail accounting, purchasing, inventory, quality control, and productivity information. The DBMS also interfaces with electronic health records, medical databases, and insurance processing company systems. These interoperability functions are growing with the push of universal electronic health records shared among appropriate healthcare professionals.

Because of this computer integration, computer availability for technicians affects workload and efficiency. Some computers are intelligent or smart terminals that contain their own storage and processing capabilities. Others are dumb terminals, computer devices with a monitor and keyboard that do not contain storage and processing capabilities. The dumb terminal is connected to a remote computer—often a minicomputer or a mainframe at the main pharmacy, company headquarters, or home office—that stores and processes the data, such as patient information, prescription history, and insurance coverage. This computer communication involves the transmission of data signals through cables or the air via transmitters, receivers, and satellites. Some chain pharmacies have a terminal dedicated for each pharmacist and pharmacy technician. In independent pharmacies, both pharmacists and technicians may work at one or more computers throughout the pharmacy during a shift. Technicians sign on with their user names and passwords for each computer they will be working on; pharmacists must do likewise.

Types of Prescriptions

Before being able to process a prescription properly, a technician must understand the different requirements for the varying kinds of prescriptions:

an electronic prescription

a written hard copy on a prescriber’s form from the patient

a telephone or fax order from a prescriber

a verbal order transcribed by a pharmacist

a prescription on the profile

a transfer prescription from another pharmacy

a patient refill request

a partial fill

an emergency fill with prescriptions allowing no refills by the pharmacist

a prescription transferred to and from another pharmacy

It is important to learn how to handle the different kinds of prescriptions because you will encounter them all in a community pharmacy.

E-Prescriptions

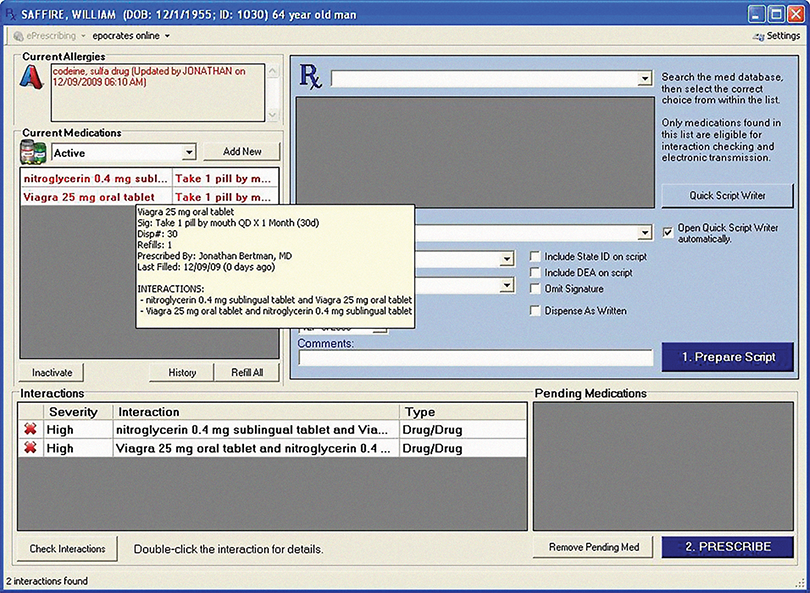

Nearly 70% of prescriptions are communicated from the prescriber to the pharmacy digitally via the internet through an examination room computer, a personal digital assistant a (PDA), tablet, or even a smart phone. These electronic or e-prescriptions (e-Rxs or e-scripts) are transmitted from the prescribers to the computers of the pharmacist or technician through a healthcare interface network, which offers online prescription processing that accesses national health and drug information systems to check the order and communicate it to the pharmacy (refer to Figure 7.2 and see Figure 7.3). Pharmacy online networks also work with the insurance processors. The most commonly used pharmaceutical healthcare networks are Surescripts and RxHub.

The direct nature of e-prescribing offers overall speed, accuracy, and improved billing. It minimizes the risk of medication errors due to illegible prescriber’s handwriting, misinterpretation of abbreviations, and difficult-to-read faxes.

For patients, e-prescribing may decrease wait times. In fact, because e-prescriptions are forwarded from the prescriber’s office directly to the pharmacy, the prescriptions are typically filled and ready to be dispensed to patients upon their arrival at the pharmacy. If a paper and an electronic transmission are both received at a pharmacy, one should be voided.

Electronic Prescriptions for Controlled Substances In addition, e-prescriptions for controlled substances are considered safer from forgeries than the handwritten prescriptions because the prescribers have to go through numerous steps to initiate the prescription.

As with handwritten prescriptions, e-prescriptions must have the DEA number and state eligibility for prescribing these substances, but they must also have a controlled-substance identity authentication and a protection software program and/or a private cryptographic key that encrypts, or puts into secret code, the prescriber’s information to protect it from web theft. The prescriber’s identity must be authenticated and double-protected by at least two of the following:

a password or response to a security question

a biometric, such as a fingerprint or eye scan

a hard token that serves as a cryptographic or one-time password device

This does not mean that forgeries cannot happen through hacking, the carelessness of a prescriber, or the spying of an assisting associate, but forgeries are far less likely than with handwritten prescriptions.

Figure 7.3 E-Prescription

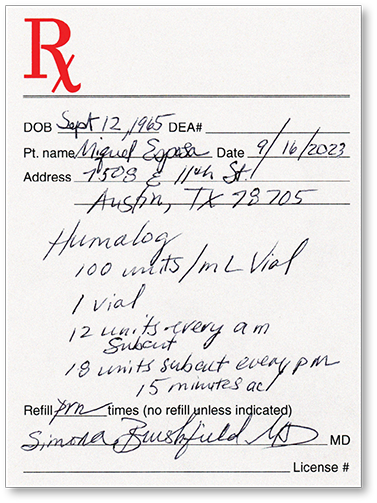

Figure 7.4 Handwritten Humalog Prescription

The prescription should be legible and contain all the information needed for the technician and the pharmacist to fill it accurately.

Written Prescriptions

The traditional written prescription (Rx) on a preprinted form is typically dropped off at the pharmacy counter or at the drive through window (see Figure 7.4). If the pharmacist is unclear on any component of the prescription, the technician or the pharmacist should call the prescriber’s office for clarification; the name of the physician’s representative along with the clarification should be entered onto the hard copy of the prescription and into the computerized patient profile.

In most pharmacies, the hard copy is scanned and recorded permanently into the electronic patient profile (see Figure 7.5). Prescriber information, the NDC number of the dispensed drug, and a photo of the drug are all recorded to minimize the chance of the wrong drug being entered into the computer or being dispensed. If the pharmacist or the technician misses entering the refills on the original prescription, the scanned prescription can be accessed to confirm the error.

Figure 7.5 Written Prescription Processing

A written prescription can be scanned into a patient-specific electronic profile by the technician or the pharmacist.

Medicaid Prescriptions and Tamper-Resistant Prescriptions Medicare and Medicaid encourage secure e-prescriptions. If handwritten, prescriptions for Medicaid patients have distinct requirements. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in cooperation with each state board of pharmacy requires that all prescriptions for Medicaid patients be written on a tamper-resistant prescription pad. A tamper-resistant prescription (TRP) is specifically designed to prevent copying, erasing, or alteration. Each state establishes its own acceptable characteristics for a TRP. Examples include some combination of chemical-protected paper, heat-sensitive image or other security features, and pantographs indicating “void” or “illegal” if copied. In Georgia, for example, the prescription for a Medicaid patient must possess one or more of the following requirements:

a gray security background—the word “VOID” appears when script is photocopied

an identifier production batch number in the margin on the front of the sheet

a consecutive number in the upper left-hand corner of the sheet

erasure protection—a white mark appears when erased with an ink eraser

a security watermark on the back of the sheet—hold up to the light at a 45-degree angle to view (when duplicated, the artificial watermark is not visible on the copy)

a coin-activated security mark on the back of the script—rub with a coin to validate the script

If an audit reveals that prescriptions for Medicaid patients were not written on TRP paper or authenticated by pharmacy personnel, claims for reimbursement may be denied. A prescription for a controlled substance not written on a TRP paper should particularly cause closer scrutiny by both the technician and the pharmacist.

IN THE REAL WORLD

IN THE REAL WORLD

Surescripts, an information technology company that monitors e-prescriptions between healthcare organizations and pharmacies, reviewed more than 40 million of its prescription records in a study to compare the effectiveness of e-prescriptions versus paper prescriptions on first-fill medication adherence (the picking up of new prescriptions by patients). First-fill pickups on e-prescriptions improved by 10% over traditional written, verbal, and faxed prescriptions.

Problems, however, can still occur in electronic systems. In 2014, Surescripts discovered that one of its data sources contained glitches with special characters corrupting the decimal points in its listing of medication dispensing levels. For instance, what should have been “ramipril 2.5 mg capsules” was being transmitted as “ramipril 25 mg capsules.” Surescripts alerted pharmacies and pulled this source from its database until the problem could be resolved. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) reminds technicians, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals to question and verify any medication dosages reported in medication histories or data that seem strange or out of the normal ranges.

Telephone

Telephone prescriptions must generally be taken by a pharmacist, though in some states such as South Carolina, a certified pharmacy technician may take a verbal prescription over the telephone (as well as handle transfers in or out of the pharmacy). Generally, the pharmacist transcribes the telephone order onto a prescription pad and verifies its accuracy. Then the technician can enter the information into the patient profile and initiate the dispensing process. The pharmacist then checks the prescription a second time after technician order entry or during the final verification step.

In most states, only the pharmacist may take verbal prescriptions over the phone.

Fax Orders

Medical offices that are not yet equipped to send e-prescriptions may elect to fax new or refill medication orders to a dedicated fax line in the pharmacy. Fax orders contain all the necessary patient demographic, prescriber, and medication information to fill the prescription. Faxed prescriptions are scanned and/or entered into the patient profile by the technician (or the pharmacist) and verified by the pharmacist before being filled. With very few exceptions, C-II controlled prescriptions cannot be faxed and require a hard copy and signature from an authorized prescriber registered with the DEA. If a fax number is not available for the prescriber, the pharmacist may need to call the medical office for refill authorization.

Pharm Fact

Pharm Fact

As e-prescriptions are on the rise, fax prescriptions are being phased out by many healthcare prescribers.

Prescriptions Not Yet Due

Not all prescriptions are filled and delivered on the same day as they are received. Often a patient may present a new written prescription that does not need to be (or cannot be) filled until a future date. The pharmacy may also receive a similar verbal, faxed, or electronic prescription. This type of prescription is referred to as placing a prescription on profile, and it may be on hold for a variety of reasons. For example, the patient may have sufficient medication at home, especially if the dose was lowered. Or the prescription may be held because the patient does not have the cash on hand to pay for all the prescribed medications. A prescription may also be held due to lack of insurance coverage until a future date. With the exception of controlled drugs, prescriptions are valid to be filled from one year of the original date written.

If a handwritten prescription to be held is for a C-II drug, it is typically stored in an alphabetized file box and listed on the patient profile for easy retrieval at a later date, not to exceed six months. Some state boards of pharmacy—as well as the policies of individual pharmacies—may not permit the storage of C-II prescriptions, and these prescriptions must be returned to the patient. Check with your pharmacy to see its policy on profiled C-II prescriptions.

Refill Requests

Refill requests in person or over the phone are relatively easy to process if the patient has the prescription container or can tell you over the phone the prescription number on the label. Some pharmacy software systems have the capability to prepare automatic refills when their time is due if patients desire it. Since the prescription information for refills has already been previously entered into the patient profile and verified by the pharmacist, the dispensing time is shorter. The technician first verifies that a refill is allowed and not early for the medication (based on the inscription and days’ supply calculation) and then forwards the request for pharmacist review.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

Many insurance groups are opening their own mail-order pharmacies and putting restrictions on three-month supplies to encourage patients to use their pharmacies instead of local pharmacies. Knowing customers’ names and faces encourages them to return.

Most pharmacies and insurance plans allow medications to be refilled approximately five days prior to the next scheduled refill date. For example, a patient may request that a three-month supply of medication be filled to save on copayments or to avoid traveling to the pharmacy each month. If a prescriber writes a prescription for a 3-month (90-day) supply, and the insurance company approves it, there is no problem. However, if the prescription was written for a 30-day supply with two refills, the pharmacy technician or pharmacist must sometimes call the prescriber’s office to get approval for the full 90-day supply at one time. If the prescription is filled without documentation of prescriber approval, then some state boards may consider this an overstepping of the pharmacist’s role into that of the physician—and possible legal ramifications may ensue.

No Refills Under certain circumstances, no refills are permitted—despite what the medication label indicates. Prescriptions that may not be refilled include those that are:

more than 12 months old,

for a C-II drug where no refills are allowed without a new prescription,

for a controlled drug (C-III–IV) written more than six months ago or already refilled five times,

for a controlled drug that has been previously transferred to another pharmacy,

from a hospital emergency room (ER), commonly only for short-term use with no refills,

hospital discharge prescriptions (most allow no refills).

In any of these situations, pharmacy technicians should explain the common protocol to patients. They need to contact their primary care physicians to refill any prescription originating from the ER or a hospital discharge.

Partial Refills At times, a pharmacy will not have enough drugs in its inventory to completely fill or refill a prescription, so it will dispense a partial fill or a two- to five-day supply to hold the patient over until new drug inventory is received. For example, a patient may present a prescription for a 3-month, or 90-day, supply of gabapentin, but the technician discovers that the inventory has stock containing a total of only 150 capsules.

Work Wise

Work Wise

Just before holidays and vacation seasons, many customers may ask for early refills or need reminders not to count on getting refills in foreign countries. To refill prescriptions early, technicians have to ask the patients’ insurance companies for vacation overrides.

Common practice is to issue a five-day supply (in this case, 15 capsules) and order the remaining medication for the next business day. The five-day supply hopefully will cover the weekends or holidays and not inconvenience the patient. The remaining 135 capsules in inventory can be used for other prescriptions for gabapentin received later that day. Obviously, the technician must explain the reason for the partial fill to the patient and say when the remainder of the prescription can be picked up. The patient may be billed only for the amount of drug dispensed at that time or for the entire amount when picked up later, depending on store policy.

Early Refills A patient may ask for an early refill due to special circumstances, such as an upcoming vacation or a lost prescription. Insurance companies often will reject an early refill automatically. The pharmacy technician may offer to call the insurance provider to try to get approval for a “one time” override for an early refill. If not granted, the patient may need to pay for the medication until insurance covers the next refill.

If a refill request is made too early (more than five days before the refill date), then the request will definitely be rejected by a third-party insurance company. For example, suppose that a patient requests a refill of Motrin (ibuprofen) 600 mg #90, 1 tab tid prn for 30 days. The patient’s profile indicates that the prescription was filled on April 1. Because this is a 30-day supply, the refill is then due May 1, which means that the technician can initiate the refill request on or after April 25. Each pharmacy and insurance provider has its own policy outlining the procedure for handling early refills, especially for controlled substances. When needed, the technician should explain the pharmacy’s policy and reasons for it to the patient.

Emergency Refills An emergency fill is for a short-term emergency supply of a needed medication for a chronic condition, such as high blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol, or epilepsy. Patients with these or related conditions typically have prescriptions with limited refills, requiring them to schedule follow-up visits with their primary care physician for monitoring and blood work. Even so, they may need a refill to bridge the gap at night or on weekends when refill authorization is not feasible. Most states allow pharmacists to use their best professional judgment to provide a short-term emergency supply (usually two to three days) of an essential medication until refill authorization can be obtained.

Pharm Fact

Pharm Fact

In most states and pharmacies, birth control medications are not considered eligible for an “emergency fill,” though it may feel like an emergency to many patients. Technicians have to explain the policies.

Typically, there is no patient charge for this temporary emergency fill. When the prescriber renews the prescription, the amount of medication “loaned” to the patient is subtracted from the refill. For example, if three tablets of amlodipine 10 mg are loaned and a new prescription is received the next day for #90, then 87 tablets will be dispensed, but 90 tablets will be billed to the insurance company. Emergency fills of controlled drugs are seldom permitted except under extremely unusual circumstances or for pain relief for terminally ill patients.

Transfer Prescriptions

At a patient’s request, prescriptions can be legally transferred from one pharmacy to another. Common transfer reasons may be insurance coverage and customer service issues, including the pharmacy’s hours of operation or location. According to the law in most states, only a licensed pharmacist can transfer or copy a prescription from (or to) another pharmacy, and the new pharmacist must personally talk to the pharmacist at the originating pharmacy.

Safety Alert

Safety Alert

Remember that controlled substance prescriptions can be transferred only once in the lifetime of the prescription unless the transferring pharmacies share an online, real-time database. Then they can transfer as many times as there are allowed refills. However, C-II substances cannot be transferred. A written prescription is always necessary for C-II substances, except in an emergency if verified by the prescriber.

Transfer Out A transfer out is a prescription refill in which the pharmacist, at the request of a patient, transfers the refill to a new pharmacy. Controlled prescription drugs, with the exception of C-II drugs, cannot be transferred to be refilled “early” and can be transferred only one time. If the prescription was already filled at your pharmacy but not yet picked up by the patient, then it must be retrieved from the storage bin and returned to inventory. The medication charges must then be reversed with the insurance provider.

Transfer In When a previously filled prescription arrives at a new pharmacy, it is called a transfer in prescription. After the phone discussion between the two pharmacists, the originating pharmacy provides over the phone, fax, or electronic transmission all the relevant information (including any remaining refills on the prescription) to the transfer pharmacy. The originating pharmacy must agree to “close” the prescription to any remaining refills.

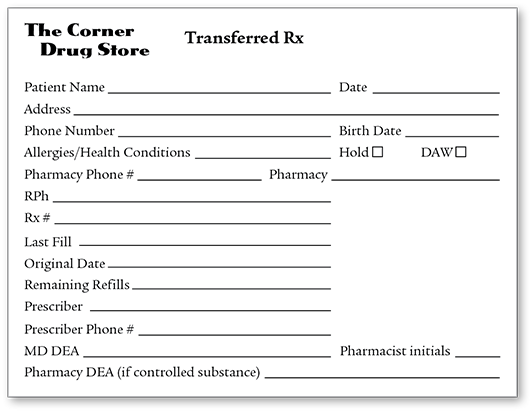

Transfer-in prescriptions require additional time to find the phone number and make the telephone call, wait on the phone to connect one pharmacist to the other, transcribe the prescription information, and enter the prescription into the patient profile. The transfer process is easier if the patient presents to the new pharmacy the medication vial containing the medication’s name, dosage, prescription number, and the originating pharmacy’s name and telephone number. However, the transfer can also be made if the patient supplies their name and birth date, the name and phone number of the originating pharmacy, and the name of the medication to be transferred. Figure 7.6 shows an example of a form that may be used to document information that must be received for each transfer prescription.

Figure 7.6 Information Needed for a Transfer Prescription

A form like this on paper or online must be filled in by the transfer-out pharmacy and must be received by the transfer-in pharmacy.

If the prescription is for a new patient, then more time is needed to get necessary demographic, allergy, health and medication history, and insurance information to complete the patient profile. If the transfer prescription has no remaining refills or if the original date is beyond one year or, in some cases, six months, the technician or pharmacist must call the physician’s office to request a new prescription.

Many chain pharmacies have a shared database of patient profiles, which allows transfers without the need of a telephone call and verification of patient and medication information. An affiliated pharmacy in Alabama would typically send an electronic message to the pharmacy in Georgia to notify personnel of the transfer. By law, the transfer of controlled substances still requires a telephone call in most states.

Mail-Order Prescriptions

For mail-order pharmacies, new patients for long-term medications generally get two prescriptions from their prescribers—one sent online to a community pharmacy for immediate filling of a 30-day supply, and a second one in paper handed to them for a 90-day supply. The patients fill out an online survey for their patient profile and then print out and send in the order form along with their paper prescription. Once received, the technicians and pharmacists verify and check the prescription in the same way as a regular community pharmacy. If there are problems, they call the patient or the prescriber for more information before filling the prescription. Refills are done through phone calls or by checking the refill box online.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

Many abbreviations are particularly easy to mix up. To access the ISMP’s List of Error-Prone Abbreviations, Symbols, and Dose Designations, pharmacy technicians should visit https://PharmPractice7e.ParadigmEducation.com/ISMP-abbreve.

Signa and Subscription Abbreviations

To translate any prescription for filling, one must know the common abbreviations used in the signa and subscription. (Examples are shown in Table 7.4 and a more complete listing in Appendix B.) This knowledge is essential to avoid any misinterpretation of prescription abbreviations, which may result in a serious medication error due to entering the wrong drug, wrong dose, or wrong directions.

Safety Alert

Safety Alert

Show all prescriptions with questionable authenticity or illegible handwriting to the pharmacist before entering them into the computer database.

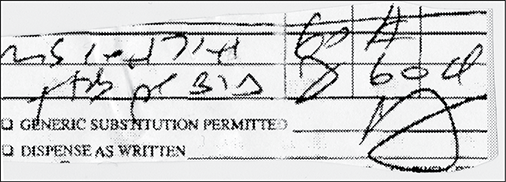

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) has called for the complete elimination of handwritten prescriptions to avoid problems from illegible or confusing handwriting and for the elimination of some that are easily confused or misread, such as qid (four times daily) and q6h (every six hours), in favor of using the appropriate words.

This prescription for morphine sulfate 60 mg is indecipherable in many ways. A follow-up call to the prescriber’s office is necessary.

Table 7.4 Common Prescription Abbreviations

Category |

Abbreviation |

Meaning |

|---|---|---|

Amount |

cc* |

cubic centimeter (mL) |

g |

gram |

|

gr |

grain |

|

gtt |

drop |

|

mg |

milligram |

|

mL |

milliliter |

|

qs |

a sufficient quantity |

|

tbsp |

tablespoonful |

|

tsp |

teaspoonful |

|

Dosage form |

cap |

capsule |

MDI |

metered-dose inhaler |

|

sol |

solution |

|

supp |

suppository |

|

susp |

suspension |

|

tab |

tablet |

|

ung |

ointment |

|

Time of administration |

ac |

before meals |

am |

morning, before noon |

|

bid |

twice a day |

|

hs* |

at bedtime |

|

pc |

after meals |

|

Time of administration |

pm |

evening, after noon |

prn |

as needed |

|

q6h |

every 6 hrs. |

|

qid |

4 times a day |

|

tid |

3 times a day |

|

tiw |

3 times a week |

|

Site of administration |

ad* |

right ear |

as* |

left ear |

|

au* |

both ears |

|

od* |

right eye |

|

os* |

left eye |

|

ou* |

both eyes |

|

po |

oral, by mouth |

|

pr |

rectally |

|

sl |

sublingual (under the tongue) |

|

top |

topical (skin) |

|

vag |

vaginally |

* These abbreviations, although commonly utilized by practitioners, are easily misread. Consequently, the abbreviations have been designated as dangerous by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP).