7.7 Stock Selection and Medication Preparation

Once the prescription’s entry into the computer has passed through the DUR and been approved for insurance, the pharmacist approves it and prints a medication container label (and any required medication information) to initiate the filling process. This label includes patient demographics, insurance billing information and copayments, the name of drug being dispensed (name, strength, form, and quantity), the National Drug Code, and the potential for refills on the prescription.

Pharm Fact

Pharm Fact

One in four filling errors is due to a confusion of names, which is why NDC checks are essential.

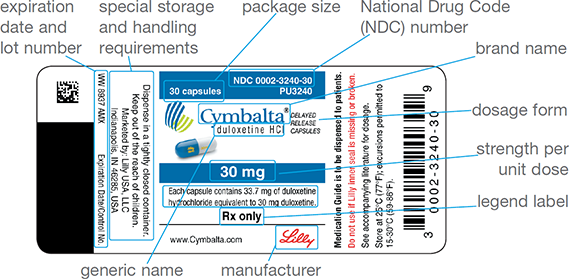

To identify the exact manufacturer, drug, dose, and package size, the technician uses the NDC number to (1) retrieve the correct manufacturer’s stock bottle, or bulk inventory container, from the storage by matching the NDC numbers of the label and the stock bottle; (2) select the proper size medication container based on the quantity prescribed; and (3) fill the prescription with the required number of dosage units (such as tablets or capsules) from the stock. The stock drug bottle should be returned to its correct location on the inventory shelf. One label is affixed to the container, and the other is filed with the original prescription. See Figure 7.10 for a sample stock drug bottle label.

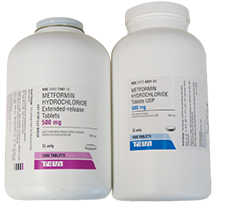

Care, of course, must be taken with stock bottle selection. A common error is the selection of the wrong stock drug bottle, dose, or package size, because different products can look-alike (similar labeling), sound-alike, or have different formulations available (SR, XL, XR, DR). Almost all community pharmacies now use bar coding to enhance accuracy. The manufacturers affix a bar code that corresponds to the product’s National Drug Code (NDC) to the stock bottles and prepackaged units. The NDC drug bar code may pull up a screen recommendation—for example, that the 250 mg of cephalexin prescribed should contain red and gray capsules with certain markings. If 500 mg of cephalexin of a different color were to be selected, the error could be identified.

Figure 7.10 Parts of a Stock Drug Bottle Label

Tablets and Capsules

The most commonly dispensed drug form in a community pharmacy is the tablet or capsule. Figure 7.11 shows the equipment and procedure for manually counting tablets and capsules. A special counting tray is used that has a trough on one side to hold counted tablets or capsules and a spout on the opposite side to pour unused medication back into the stock bottle.

Safety Alert

Safety Alert

Because of the frequency of severe patient allergies, counting equipment should be cleaned immediately after counting sulfa, penicillin, or aspirin products.

Both of these drugs are metformin 500 mg, but one bottle is immediate release and the other is extended release. Selecting the wrong bottle could result in a grave medication error and patient harm. Matching the NDC assists in accuracy.

Pharmacy technicians should minimize any direct finger contact with the oral dose forms of medications. The tablets and capsules should always be counted with a clean spatula and picked up with forceps if dropped on the counter. The spatula, tray, and forceps should be cleaned often throughout the workday with 70% isopropyl alcohol, and these items should always be cleaned after counting a product that leaves a powder residue or is known to cause allergic reactions.

Figure 7.11 Counting Tablets

(a) Tablets should be counted by fives and moved to the trough with a spatula. (b) The unneeded tablets should be returned to the stock container by pouring them from the spout. (c) The counted tablets should then be poured into the appropriately sized container.

Liquid Formulations

Liquid products (such as pediatric cough and cold syrups and antibiotic suspensions) are sometimes dispensed in their original packaging. They are also commonly poured from a stock bottle directly into an appropriately sized dispensing bottle (from 2 fl. oz. to 16 fl. oz.). Antibiotics are commonly reconstituted, or mixed with liquid, by adding distilled water to a dried antibiotic powder. In most cases, due to a short expiration period, the antibiotic suspension should not be prepared by the pharmacist or the technician (adding the distilled water) until the patient (or parent) picks up the medication. These medications should always be dispensed with an appropriate measuring device and an appropriate auxiliary label(s) such as “Shake well before using,” “Refrigerate,” or “Protect medication from exposure to light.” (These will be explained later in greater detail.) The expiration date is commonly 14 days after reconstitution and should be added to the labeling. Because antibiotics and other liquid medications taste bad, flavorings are often added.

Flavor formulas to improve the taste of liquid drugs are available and a great customer service.

It may be easier for children to adhere to drug therapy if flavor is added to their prescribed medication. Manufacturers have created appropriate flavors for pediatric liquids. In most cases, the amount of distilled water to be added to the antibiotic powder is adjusted slightly to account for the small volume added from the liquid flavoring agents.

The correct flavoring formulas for each drug and dose are provided in the computer database. For several “unpleasant tasting” drugs, such as amoxicillin/clavulanate and clindamycin, pharmacy technicians often flavor the medications without an additional charge. In many cases, the medication taste may still be unacceptable to the child. Some pharmacies have the capability to add additional flavorings upon request from a patient or a parent at a minimal additional charge.

Flavoring agents have sweetening enhancers as well as bitterness suppressors and come in many flavors: apple, banana, bubble gum, cherry, chocolate, grape, lemon oil, orange cream, raspberry, strawberry cream, vanilla, and watermelon. Formulas for flavoring agents often combine one or more agents to result in the desired flavor. They are drawn up in an oral syringe and added to the liquid suspension. Although some flavors are incompatible with a specific medication, most flavors will not interfere with active ingredient(s) of drugs. Flavors are free from dyes and sugar and are hypoallergenic, so they are safe to use for those with allergies or diabetes, or even those who are gluten or casein (milk protein) sensitive.

Flavoring drugs is a patient service that can improve customer loyalty and, therefore, customer retention. More importantly, this service improves patient compliance with the prescribed medication regimen, resulting in a happy child, a happy parent, and a happy prescriber.

Choosing Medication Containers

A wide variety of plastic vial sizes are available for tablets and capsules in various dram sizes—from 10 to 60 drams. (This is one of the few times an older apothecary unit is still utilized without difficulties.) Selecting the proper vial size is a skill that becomes easy with experience. The pharmacy software printout on the patient medication information sheet may even recommend a vial size. Liquid containers are available in various sizes, from 2 oz. to 16 oz. Most pharmacy containers are amber-colored to prevent ultraviolet (UV) light exposure, which can degrade the medication.

Amber-colored containers protect medications from UV light exposure.

All medications must be dispensed in child-resistant containers designed to be difficult for children to open. The Poison Prevention Packaging Act of 1970 requires (with some exceptions, such as sublingual nitroglycerin tablets, unit-of-use, and unit dose packages) that all prescription drugs be packaged in child-resistant containers. A container without a child-resistant top may be used if the patient requests it. For example, many older patients, especially those with arthritis, may request an exemption because they have difficulty opening child-resistant containers.

Some states require patients to sign such a request for each prescription, while others allow it to be added to the patients’ profiles for future reference. Certain OTC drugs and supplements, such as aspirin and iron, are packaged in child-resistant containers due to their potential toxicity in accidental overdoses in children.

Handling Prepackaged Drugs

Several medications are available in unit-dose blister packs, with each unit having a scored perimeter for easy tear-off. Some blister packs come in boxed packages that contain a month’s dosage supply.

Manufacturer prepackaging is provided for prescription products such as otics, ophthalmics, suppositories, creams, ointments, respiratory and nebulizer drugs, syringes, metered-dose inhalers (MDIs), and oral contraceptives. The prescription label is attached directly to the product or the box. These medications are commercially available in unit-dose (single dose) or unit-of-use (fixed number of common use doses) prepackaging, as described below. They simplify the filling process by eliminating the counting step: the technician retrieves the drug from inventory by matching the correct name, manufacturer, quantity, and strength with the prescription and verifying them with the bar code scanner. Even though these medications are prepackaged, the pharmacist must still check and approve the medication label, ensuring that the proper drug, dosage form, and amount were chosen for dispensing to the correct patient.

Unit-Dose Packaging

Each unit dose of a tablet or capsule is a single dosage that is individually packaged in sealed foil and is considered tamper-proof. For unit-dose drugs that are individually packaged, a label is commonly affixed to a resealable plastic bag. The packaging label must include the manufacturer’s name, lot number, and expiration date in addition to the drug’s name and strength. For example, a prescription of ondansetron 8 mg ODT #8 for nausea and vomiting requires that eight individually packaged unit doses be placed in a medication container or plastic bag with a medication label. Other medications commonly available in unit doses include suppositories and migraine medications. Unopened unit doses may be legally returned to pharmacy stock. (For information on unit-dose packaging, see Chapter 11.)

Unit-of-Use Packaging

A unit-of-use package is a fixed number of dosage units sealed together in prepackaging. Examples include birth control, topical ointments and creams, nasal sprays, metered dose inhalers (MDIs), eye drops, and ear drops. Unit-of-use packaging consists of a month’s supply, which is often 30, 60, or 90 tablets or capsules, a tube of cream or ointment, or a bottle of nasal spray, MDI, eye drops, or ear drops. Filling a prescription with unit-of-use packaging amounts to little more than locating the correct drug in the correct strength, verifying the NDC number, and affixing the correct medication container label.

Automated Filling Technology

To meet the demands of the increasing numbers of prescriptions, many high-volume community pharmacies, especially chain and mail-order pharmacies, have adopted automation technology to dispense with greater speed and accuracy. For example, the automated system Parata Max labels, fills, caps, sorts, and stores 188 drugs by NDC number and up to 232 prescriptions, processing up to 60% of total prescription volume of a specific community pharmacy with near 100% accuracy. Automation reduces the number of manual fills by pharmacy staff, helping to lower the cost per prescription. It also reduces the time in counting, labeling, sorting, and capping, and adds to medication safety by integrating the bar code technologies used for other retail products.

Parata Max is one of many different kinds of high-speed, high-accuracy automated dispensing systems.

In addition to bar code scanners, some higher-volume pharmacies use automated scales for liquids and powders and liquid-filling machines. For large quantities (usually greater than 100) of tablets or capsules for medication orders, automated counting machines help reduce errors. Some counting machines have internal scales that take into account the weight per unit of an individual tablet or capsule based on 10 dosage units. However, these machines are not 100% accurate and should not be used to count prescription doses for controlled drugs. Each counting machine must be calibrated and documented daily by the pharmacy technician; a measuring weight (for example, 200 g) is placed on the balance, and the device is recalibrated if needed.

Another option is the visual-precision counting equipment from Eyecon. This technology is 99.99% accurate; it documents the quantity of each prescription using scanner technology. It eliminates underfills (too little of the medication) and overfills (too much) accurately and consistently enough to use with C-II prescriptions.

Automated dispensing machines are linked to the pharmacy’s DBMS. The software can send filling orders directly to the automated dispensing device that then fills, caps, labels, sorts, and stores the prescriptions for retrieval by the technician and approval by the pharmacist.

Most chain and mail-order pharmacies utilize a conveyor belt to improve the efficiency of moving a prescription through its various steps, with different technicians doing different tasks and the pharmacist checking all technician work in the end. One technician may be entering prescriptions into the computer while another is filling the medication orders for each patient. As each medication order is filled, the labeled medication, the original prescription (if available), and printed medication information are all placed in a plastic bin and then placed onto a conveyor belt—like a mini-assembly line—for the pharmacist’s final check.