9.5 Accounting, Pricing, and Retail Math

A community pharmacy operates under the same principles as any other business—it must make a profit to survive. In other words, it must have more income than expenses to continue to provide services. One of the responsibilities of the pharmacy technician is to help ensure that inventory turns over and that the insurance reimbursements and sales are greater than the expenses.

The technician is often responsible for marking up OTC products and other merchandise by a certain percentage over the acquisition cost and marking other products down by a percentage discount. To be successful, you need to master basic mathematical skills used in markup, discount, and average wholesale price. Understanding the terminology and mathematics used in community pharmacy is an important part of the pharmacy technician’s job and can directly affect business profitability.

Acquisition Costs and Pharmacy Reimbursements

Like all businesses, pharmacies purchase their products (in other words, drugs) at a generally lower-than-retail price from a wholesaler or supplier called the acquisition cost. The wholesaler is a company that purchases drugs, supplements, and supplies directly from manufacturers and then distributes them to pharmacies from a local or regional warehouse. When purchasing as a group, the purchasing agent for a number of independent pharmacies or for a pharmacy chain negotiates favorable contract terms and a discount for high-volume purchases. The state pharmacy association sometimes can act as a facilitator for group purchasing, contracting for its members as a benefit.

For pharmacies to offer prescription discounts to cash- or credit-paying patients, pharmacists and technicians need to be well aware of a drug’s AWP, the negotiated acquisition price, and the pharmacy markup percentage.

Average Wholesale Price Versus Acquisition Cost

The average wholesale price (AWP) of a drug is the average price that wholesalers charge pharmacies for a given drug, dose, and package size. AWP has been compared to the “sticker price” on an automobile. There is generally a difference between the AWP and the actual acquisition cost, because the AWP does not include discounts for the pharmacy’s volume purchasing, prompt payment, or rebates from pharmaceutical manufacturers for brand name drugs.

Usually, the pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) (which handle insurance company claims) and other third parties reimburse pharmacies a brand drug’s AWP minus a third-party volume discount agreed upon in a negotiated contract, plus a pharmacy dispensing fee (in the range of $2.50 to $4.00 per prescription) for services rendered. The dispensing fee is supposed to cover the pharmacy’s personnel costs.

Estimating Insurance Reimbursements

Insurance companies and their PBMs calculate a prescription reimbursement price with the following formula:

AWP × reimbursement percentage rate + dispensing fee = reimbursement amount

To maximize the pharmacy’s income, it is essential to purchase a stock quantity from a wholesaler at less than AWP to make up for low reimbursement percentages. Consider the following examples.

Example 1

The drug pioglitazone (Actos) comes in a quantity of 90 tablets with an AWP of $150. The pharmacy has an agreement with the supplier to purchase the drug at the AWP minus 15% (converted to 0.15 discount rate). The insurer is willing to pay the AWP less 5% plus a $3 dispensing fee. A patient on this insurer’s plan purchases 30 tablets. How much profit does the pharmacy make on this prescription?

Step 1 |

Begin by calculating the amount of the 15% discount. $150.00 AWP × 0.15 discount rate = $22.50 discount |

Step 2 |

Use the discount to calculate the purchase price of the drug by subtracting it from the AWP. $150.00 AWP − $22.50 discount = $127.50 purchase price Therefore, the pharmacy can purchase 90 tablets for the discounted acquisition cost of $127.50. |

Step 3 |

The insurance company will pay the pharmacy the AWP less 5%. (Note: 5% = 0.05.) $150.00 AWP × 0.05 reimbursement rate = $7.50 $150.00 − $7.50 = $142.50 insurance reimbursement for 90 tablets (without dispensing fee) |

Step 4 |

Using the insurance reimbursement of $142.50 for 90 tablets, calculate the reimbursement for 30 tablets. $142.50 ÷ 3 = $47.50 Add $3.00 dispensing fee: $47.50 + $3.00 = $50.50 insurance reimbursement (for 30 tablets) |

Step 5 |

Compare this to the pharmacy’s cost of 30 tablets. $127.50 ÷ 3 = $42.50 acquisition cost for 30 tablets |

Step 6 |

To find out the profit, subtract the pharmacy acquisition cost from the insurance reimbursement. $50.50 − $42.50 = $8.00 gross profit |

Example 2

The drug amlodipine 10 mg comes in a quantity of 500 tablets and has an AWP of $80. The pharmacy has an agreement with the supplier to purchase the drug at the AWP minus 10%. The insurer is willing to pay the AWP less 5% plus a $2.50 dispensing fee. What does the insurer’s plan pay for 30 tablets? How much profit does the pharmacy make on this prescription?

Step 1 |

Begin by calculating the amount of the 10% discount. $80.00 × 0.10 = $8.00 |

Step 2 |

Use the discount amount to calculate the acquisition cost of the drug. $80.00 − $8.00 = $72.00 Therefore, the pharmacy can purchase 500 tablets for $72.00. |

Step 3 |

The PBM will pay the pharmacy the AWP less 5%. (Note: 5% = 0.05.) $80.00 × 0.05 = $4.00 $80.00 − $4.00 = $76.00 insurance reimbursement (for 500 tablets) (plus $2.50 dispensing fee) |

Step4 |

Calculate the insurance reimbursement for 30 tablets. $76.00 ÷ 500 tablets = $0.152 per tablet $0.152 per tablet × 30 tablets = $4.56 for 30 tablets $4.56 + $2.50 dispensing fee = $7.06 insurance reimbursement (for 30 tablets) |

Step5 |

Compare this to the pharmacy’s cost of 30 tablets. $72.00 ÷ 500 tablets = $0.144 per tablet $0.144 per tablet × 30 tablets = $4.32 acquisition cost |

Step 6 |

Therefore, the pharmacy’s profit on 30 tablets is: $7.06 − $4.32 = $2.74 gross profit with reimbursement |

As you can see, the lower the acquisition cost for the pharmacy, the more money there is to cover operating costs and, hopefully, generate a profit. To survive as a business, the pharmacy has to purchase each drug at a price as far below the AWP as possible. However, now the PBMs of the insurance companies are also seeking to reimburse at lower levels, so independent pharmacies with less volume in sales purchasing have less negotiating power and often struggle to survive.

Markup and Profits

Pharmacies also buy their nonprescription products from wholesalers and sell them at a higher price. Pricing of nonprescription items is primarily determined by competition in the marketplace and customer expectations.

The difference between the store acquisition cost and the customer price is called the markup.

pharmacy acquisition cost + markup = retail selling price

retail selling price – acquisition cost = markup

The accumulation of these sales markups adds up to the gross profit of the business. The gross profit must cover the overhead expenses, or operating costs, including facility rental or maintenance, technology, utilities, marketing, and other expenses. What is left over after all the expenses are paid is the net profit. The quantity of net profit from both prescription and nonprescription sales determines whether the pharmacy can stay in business. With independent stores, this money goes to the owners, and with chains, it goes to the company and its shareholders.

Getting the right amount of markup is key to the success of a community pharmacy. Too high a markup drives customers away. Too low a markup means that the pharmacy cannot meet its expenses and make enough profit to stay in business. To understand the business side of pharmacy and perhaps be promoted as a manager, you need to understand how estimating pricing and markups works.

Determining Customer Price

Each independent pharmacy or chain determines a percentage of each sale that must go toward the operation costs and profit. This percentage is called the markup percentage. To determine the exact markup to charge for a specific item, whether prescription or retail, start with the acquisition cost from the wholesaler (supplier price) and multiply it by the pharmacy’s markup percentage. (Pharmacies may have different retail versus prescription drug markup percentages.)

To calculate, turn the markup percentage into a decimal by dividing it by 100 to find your markup rate. Then take the rate and multiply the acquisition cost by that number to find the individual markup price. Add that markup price to the acquisition cost to get the retail cash price. The equations are set up as follows:

markup % ÷ 100 = markup rate

markup rate × acquisition cost = markup price

acquisition cost + markup price = cash price

Example 3

One case (twelve bottles) of esomeprazole (Nexium) 20 mg capsules are acquired for $202.28, and there needs to be a 13.64% markup to determine the customer price. What will be the cash price for one bottle of esomeprazole (Nexium)?

Step 1 |

Convert 13.64% to a decimal by dividing by 100 to find the markup rate. 13.64 ÷ 100 = 0.1364 {or } |

Step 2 |

Multiply the markup rate by the acquisition cost. 0.1364 × $202.28 = $27.590992, rounded to $27.59. |

Step 3 |

Add the acquisition cost and the markup price to find the cash price. $202.28 + $27.59 = $229.87 (for 12 bottles) |

Step 4 |

Divide the cash price for 12 bottles by 12 to find the price of one bottle. is the retail cash price for one bottle of Nexium. |

Example 4

One vial of Humulin regular insulin sells (as a nonprescription) at the pharmacy at the cash price of $100 and costs the pharmacy $70. What is the markup price, and what is the markup rate?

Step 1 |

Determine actual price markup from selling price by subtracting product expense from selling price. selling price – product expense = markup amount selling price $100.00 – $70.00 = $30.00 markup |

Step 2 |

Compute the markup percentage. markup ÷ acquisition cost = markup rate 1 $30.00 ÷ $70.00 = 0.43 |

Step 3 |

Convert 0.43 rate to percentage by multiplying by 100. 43% = markup percentage This is the pharmacy’s profit/operating expenses markup for this item. |

Determining Customer Discounts

As stated earlier, the drug stock price a wholesaler offers to a pharmacy is not always the AWP. Reduced standard rates are often established for frequent pharmacy purchasers or pharmacy buying groups. Sometimes, a wholesaler offers a lower price than its standard price in exchange for prompt payment. The independent pharmacy can then pass on the savings to the patients in a discount price. Having this discount leeway is particularly helpful for customers who are paying cash because they lack insurance and the pharmacist or technician wants to adjust the price to pass on the discount savings. To do this discounting, you need to determine the actual pharmacy acquisition cost and then provide an adjusted cost to the customer that will still cover the pharmacy dispensing fee. The calculation equations look like this:

usual negotiated wholesale price × prompt payment discount rate =

amount of discount

usual wholesaler price − discount = discounted acquisition cost

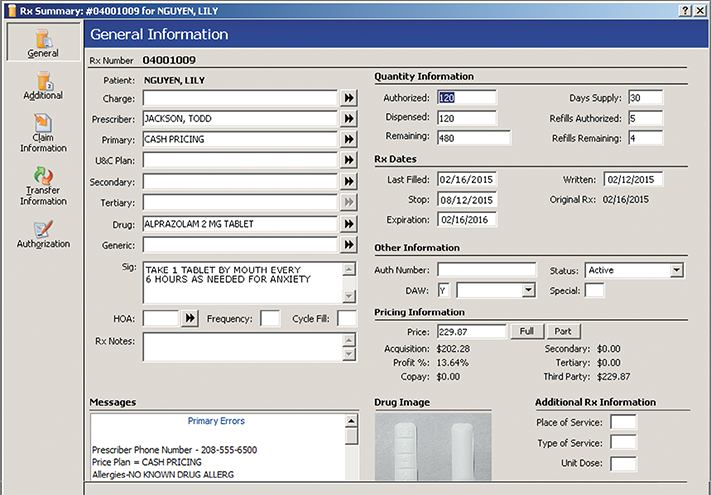

On this screen shot, the different pricing levels that are associated with a prescription price are visible: the acquisition cost, profit % (markup percentage), copay, and third-party fee.

Example 5

Assume that the pharmacy usually purchases five cases of hydrocortisone 1% cream at $100 per case. If the account is paid in full within 15 days, then the supplier (wholesaler) offers a 15% discount on the purchase. What is the discounted acquisition cost?

Step 1 |

Calculate the usual wholesale purchase price for quantity needed. quantity of product × wholesale price per unit = typical acquisition cost cases1 cases × $100.00 per case = $500.00 |

Step 2 |

Calculate the 15% discount for payment within 15 days. quantity acquisition cost × promptness discount rate = amount of discount $500.00 × 0.15 = $75.00 |

Step 3 |

To obtain the discounted acquisition cost, subtract the wholesaler discount amount from the original price. total purchase price − discount = discounted acquisition cost $500.00 − $75.00 = $425.00 |

Step 4 |

To obtain the discounted price per case, divide the discounted acquisition cost by the number of cases. |

Step 5 |

Finally, to calculate the discounted price per tube, divide the case price by the number of 1 ounce tubes in the case, which is 30. The pharmacy acquisition price is rounded to $2.83 per tube. |

Step 6 |

If the pharmacy wants a markup percentage of 20% per tube, it would be as follows. $2.83 × 0.20 = $0.566 rounded to $0.57 cents So the pharmacy would be able to add up to $0.57 to the $2.83 cost for a $3.40 customer sales price. |

Example 6

A bottle of 100 count zolpidem 10 mg has an AWP of $100, and the acquisition cost for the pharmacy is $40 for 100 tablets. A prescription for a month’s supply of medication is 30 tablets. If the pharmacy charges the AWP for the prescription, what is the markup price for the prescription?

Step 1 |

Begin by calculating the wholesaler’s standard cost per tablet by dividing the price by the quantity, and doing the same for the acquisition cost per tablet. $100 ÷ 100 = $1.00 per tablet average wholesale price $40 ÷ 100 = $0.40 per tablet pharmacy acquisition cost |

Step 2 |

Then, calculate the wholesale costs for the quantity of tablets needed (30). quantity × AWP per tablet = wholesale price for prescription 30 tablets × $1.00 per tablet = $30.00 30 tablets × $0.40 per tablet = $12.00 |

Step 3 |

Next, subtract the difference between the two: $30 – $12 = $18. This $18.00 is the markup from the actual acquisition cost and the profit leeway. If insurance will not pay for the prescription, rather than charge the cash-paying patient the full $30 AWP, the pharmacist could allow the technician to set the cash price lower, say to $24, which is a $6 discount from the average wholesaler price. |

Step 4 |

To figure out what percentage discount you are offering at this price, divide the consumer discount amount by the original wholesale price. The pharmacy can offer a cash price of 20% price savings so that the customer pays $24 instead of $30. This deal is even lower than the wholesale price. The $12 of markup adequately covers the operating costs and a pharmacy dispensing fee, while extending goodwill to the customer. Personnel working in independent pharmacies can make these cost adjustments, whereas personnel working in chain stores generally cannot. |

Accounting Profitability and Productivity Reports

The daily functions of a pharmacy include running many different kinds of reports, often done by the pharmacy technician, including inventory orders, postings, pricing, accounts receivable, accounts payable, billing, third-party receipts, DEA prescribing, HIPAA compliance, controlled-substance compliance, and others. Knowing your way around these reports can lead to greater responsibilities and, at times, promotions.

End-of-the-Day Report

At the end of each day, the pharmacist or technician prints out an end-of-the-day report, or daily audit log, from the pharmacy software. The report gives a thumbnail sketch of the profitability of the pharmacy based on that day’s productivity. It documents the various computer logins by pharmacists and technicians, the prescriptions filled, costs accrued, and payments made.

Put Down Roots

Put Down Roots

The inventory expression par in par levels came from an acronym for periodic automatic replenishment.

The report lists not only the total number and drug names of all prescriptions dispensed per pharmacist, it also lists the AWPs, acquisition costs, selling prices, profit for each prescription sold, and each PBM billed. Categories of the report include a line-by-line breakdown description of the prescriptions/refills, a breakdown of the costs for these in each payment plan and the profit margins, and a daily cost analysis breakdown for each plan/payment system based on these lists. This report is signed and dated by the pharmacist to keep on file for future audit purposes and as proof that the billed drugs were dispensed to the patients. The pharmacy manager reviews all this information, which is helpful in negotiating annual renewals of the contracts with each PBM and wholesaler.

Cost-Benefit Analysis Spreadsheets

Technicians often generate the daily reports, and, from these reports, the computer can generate weekly, monthly, and yearly cost-benefit analysis spreadsheets. The itemized tables on these spreadsheets identify the costs invested, compared to the benefits or sales received and the present business net value and income. They tally direct expenses (such as cost of inventory and pharmacy personnel) and indirect overhead expenses (payroll and benefits, utilities, insurance, legal fees, rent, computers, etc.), as compared to sales income and third-party reimbursements. Technicians who become familiar with all these reports can build an in-depth knowledge that will allow them to move forward in business management.

One of the largest elements in the expense column is the cost of the drugs that need to be held as stock for prescriptions. The entire stock of pharmaceutical and retail products on hand is known as the inventory (which will be explained in more detail to come). Over time, these end-of-the-day reports, cost-benefit analysis spreadsheets, and itemized inventory reports can track trends useful for inventory investment and management, purchasing, and retail marketing.

The pharmacy inventory must be carefully maintained to keep the costs down by having on hand what is needed without excessive extras.