9.6 Inventory Management

Community pharmacies must stock, or have ready access to, all drugs that may be desired by their customers or prescribers. Technicians assist in the everyday details of maintaining well-stocked but not overstocked shelves. They locate stock and label shelves; store products appropriately; restock, checking expiration dates and rotating products; and document reorder levels. Checking for expired vitamins and herbs is especially important because they can lose their labeled potency quickly. Technicians are also responsible for stocking the supplies they need for filling and processing prescriptions (various sizes of vials and bottles, medication and auxiliary labels, measuring devices, paper, and other supplies), making sure that they are reordered as needed.

Stock Levels and Inventory Value

Inventory value is defined as the total cost of the entire stock on a given day. The inventory includes prescription and OTC drugs, dietary supplements, medical and home health supplies and equipment, and front-end retail and impulse merchandise. Unlike some businesses, pharmacies must keep some slow-moving products on their shelves as a service to the few customers who will need them medically. If the pharmacy frequently runs out of needed supplies and medications, this causes great inconvenience to patients who will often just go to a different pharmacy. So pharmacies set periodic automatic replenishment (PAR) levels for each item, or minimum levels when each stock item needs automatic reordering.

Often, community pharmacies have $150,000 to $300,000 or more in inventory value on their shelves. Drug stock is generally the pharmacy’s biggest expense. Pharmacies must absorb the costs of the drug inventory they purchase until the stock is sold and the insurance reimbursements are received, which can sometimes take four to eight weeks. That is why keeping track of inventory and specific drug turnover is very important. Returning unopened, unused extra stock is also key.

An excessive inventory ties up capital in the inventory, hinders the ability to invest in other areas, such as marketing and staffing, and incurs wastage due to product expirations. It also increases the likelihood of theft. Therefore, inventory levels must be kept adequate but not excessive, with a rapid turnover of drug stock on the shelf.

Purchasing Relationships and Contracts

As each drug prescription is filled, the pharmacy operations software automatically deducts the amount from the stock inventory. At the end of each day, a reorder list for the next business day is automatically generated, based on the PAR restock level for each individual drug set in software by the pharmacy. Many pharmacies use software that not only automatically generates the daily reorder lists, but also generates the specific drug orders with the established wholesalers.

Before any purchasing can happen, relationships with those who distribute, store, or manufacture specific drugs must be established. Purchasing is defined as acquiring products for use or sale. Purchasing contracts can be negotiated by an individual pharmacy or with other pharmacies as part of a group purchase contract.

Primary Wholesaler Purchasing

When pharmacies secure a contract with a wholesaler to be their primary supplier, they can receive the fastest moving products from a single source for the best negotiated price. This saves them from establishing contracts with multiple manufacturers or suppliers of brand name and generic pharmaceuticals. In most primary wholesaler purchasing, the pharmacy orders from a local or regional vendor that delivers the products to the pharmacy on a daily basis. The advantages include scheduled deliveries and ordering, automatic online ordering, reduced turnaround time for orders, lower inventory and lower associated costs, discounts, and reduced commitment of time and staff. The turnaround time for receipt of drug orders is usually the next business day, with the exception of weekends and holidays.

Disadvantages include higher purchase costs for individual stock items, occasional supply shortages (called back orders), and unavailability of some pharmaceuticals.

Prime Vendor Purchasing

In some situations, pharmacies need to work with more than one vendor, getting a large amount of stock from two or more suppliers. When pharmacy planning shows that a certain amount of money will for certain be spent on an established amount of drug products, the pharmacy may be able to set up a prime vendor purchasing contract with one of these vendors to secure a discount for high-volume purchasing. This is an exclusive agreement made with a wholesaler or warehouse to continually purchase a specified percentage or dollar amount toward different types of ordering and delivery methods. Prime vendor purchasing offers the advantages of lower acquisition costs, competitive service fees, electronic order entry, and emergency delivery services. Prime vendor purchasing is common in both retail and hospital pharmacies.

Just-in-Time Purchasing

To provide less outlay of funds at one time, pharmacies can also use just-in-time purchasing, which involves frequent purchasing in smaller quantities (often of less frequently requested items or for more expensive prices because of the convenience) that just meet supply needs until the next ordering time. Just-in-time (JIT) purchasing reduces the quantity of each product on the shelves and thus reduces the overall amount of money invested at one time in the inventory.

However, such a JIT system can be used only when supplies are readily available locally and pharmaceutical needs can be accurately predicted. Automation can enhance the accuracy of replacing needed inventory levels of drugs. In large chain pharmacies, a regional or centralized warehouse owned by the corporation generally provides the once-weekly purchasing. A local wholesaler is then used for any JIT brand name and out-of-stock (OOS) drugs needed on a day’s notice. For independent pharmacies on a limited drug budget, JIT purchasing is more the norm.

Technicians need to keep close track of the inventory, especially the most frequently purchased pharmaceuticals, to assist in deciding what needs to be purchased and how quickly.

Purchasing Orders

The technician reviews and verifies each of the drugs listed on the end-of-the-day reorder list and purchase orders to process them and alerts the pharmacist to the Schedule II drugs needing attention (generally only the pharmacist orders these). If the pharmacy is on a strict daily drug budget, you need to exercise good judgment and prioritize which drugs will be ordered for the next business day and which can wait. It is not uncommon for an independent pharmacy to wait to order an expensive drug rather than keep it in stock on the shelf.

When ordering next-day inventory, the technician assesses the predicted new prescriptions or refills for (1) OOS items; (2) partial fills; and (3) stock replenishment. Special orders for seldom-stocked high-cost injectable products often require additional delivery time directly from the manufacturer if they are not in the wholesaler’s on-site inventory.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

When a patient does not pick up a prescription medication and it must be returned to stock, it needs to remain in the patient container to be placed back in the inventory with all patient information blacked out. The medication cannot be poured back into the stock bottle.

A small independent pharmacy often uses computer tracking or a manual logbook to record inventory that needs to be replaced. After a time, the technician will develop a good sense for how fast drug products move off the shelves and when they need to be reordered by watching the usage and seasonal patterns. For “fast movers,” the purchase decision is often based on the most economical order quantity or best value (such as ordering capsules in a 1,000 count size rather than 100 count size or buying a case of antacid liquid rather than one or two bottles).

Each time wholesale drugs are purchased, the product, quantity, and price are entered into the computer database. Besides the PAR levels for each drug item, pharmacies usually have an inventory range—a maximum and a minimum number of units to have on hand. Orders are calculated from these levels.

Use this formula to calculate the minimum order amount:

minimum inventory − present inventory = minimum order amount

Here are some examples of common stock dilemmas:

Example 7

The maximum inventory level for amoxicillin 500 mg capsules is 1,000 capsules. At the end of the day, the computer prints a list of items to be reordered. The list indicates a current inventory level of 225 amoxicillin capsules; the minimum quantity—and the point to reorder automatically—is set at 250 capsules. Has the automatic reorder level been reached? Each stock bottle contains 500 capsules. How many should be ordered?

250 capsules − 225 capsules = 25 capsules less than minimum level

Because the stock level has dropped under the minimum number needed to reorder, the automatic reorder or manual reorder will be processed for one bottle of 500 count 500 mg capsules.

Example 8

The maximum inventory level for cyclobenzaprine 10 mg tablets is 500 tablets and the minimum is 200. At the end of the day, the computer printout list indicates a current inventory level of 375 cyclobenzaprine tablets. Will the capsules be reordered?

200 tablets − 375 tablets = (−)175 tablets

Nothing needs to be reordered because 175 is the surplus above minimum levels.

Periodically, stock levels and ranges need to be modified or updated. For example, the software may indicate that there are 120 tablets of 300 mg ranitidine remaining in stock. If the minimum reorder level is 100 tablets, the drug will not be on the generated reorder list. However, if you retrieve the drug from the shelf and find only 25 tablets remaining, you will update the actual inventory count in the system so that the drug can be ordered for the next business day. (You and the pharmacist will need to try to figure out where the extra stock went.) Seasonal adjustments also need to be made, such as stocking more allergy products in the spring, sunscreen products in the summer, flu vaccine in the fall, and antibiotics in the winter. If a new medication is increasingly prescribed in your geographical area, its stock level will need to be increased.

Processing Order Deliveries

Once an order is delivered from a wholesaler, warehouse, or other pharmacy, the technician must go through a number of processes.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

When a medication is discontinued, or no longer manufactured, you will need to ask the pharmacist to discuss an alternative medication with the prescriber.

Receiving

When the wholesale delivery arrives, the process of receiving begins, which is a set of procedures to legally check in and accept the order. The pharmacist or the technician first must sign an invoice from the wholesale representative, verifying the receipt of the correct number and type of totes or boxes. Totes are the plastic containers that contain specialized medications, including those for refrigerated items (in cold packs) and controlled substances. These all come sealed. A separate invoice is usually required for the receipt of controlled substances. The pharmacist should check for and document intact seals and the contents of totes containing controlled substances.

Shipment contents need to be carefully checked for their National Drug Code (NDC) numbers, price updates, and expiration dates, and then posted in the inventory software program so that everything lines up at the cash register.

Once checked by the pharmacist, you as the technician must then carefully match the pharmaceutical products received against the purchase invoice for the correct product items (matching names and bar codes), manufacturer, quantity, product strength, package size, and condition. In the case of a damaged or an incorrect shipment or an incorrectly shipped product (not stored properly), you should notify the wholesaler immediately for authorization to return the defective shipment and replace inventory as soon as possible.

Occasionally, a pharmaceutical product is temporarily or permanently unavailable from a wholesaler. Drug shortages can be due to manufacturing quality control issues, FDA or voluntary drug recalls, expirations, or discontinuations. First determine the reason for the unavailability—for example, the drug is (1) on back order; (2) being recalled by the manufacturer; or (3) being discontinued. If the product is not expected to be received the next day, the pharmacist should then identify a therapeutically equivalent product with permission from the prescriber. Alternatively, the pharmacy could consider borrowing the drug from another local pharmacy or one in the corporate chain if a supply of the drug is available.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

When filling prescriptions for specially ordered, high-cost drugs, do not attach the patient medication label to the drug packaging. Attach it with a rubber band or place it with the packaging in a resealable plastic bag, so it can be returned to the warehouse if not picked up.

Posting

As the inventory order is checked and approved, it is important that the order is accurately posted. Posting is the process of updating inventory in the pharmacy software database and reconciling any differences between the new and current stock. This process includes checking the newly received drug inventory for NDC numbers, expiration dates, and drug cost updates.

Any large price increases should be brought to the attention of the pharmacist for verification. To highlight these differences, you can affix stickers to the received unit stock bottles to document the wholesaler’s item number and pricing information. However, be careful where you stick them so that they do not harm the original label; if it looks worn or tampered with, the stock cannot someday be returned to the wholesaler for credit. Also, it is the recommended practice to avoid affixing medication labels to the original manufacturer packages for high-cost drugs in the event that the patient cannot afford them, and the drugs should be returned.

Once posted, the delivered drugs should immediately be appropriately stored—at room temperature, refrigerated, or frozen—depending on the requirements listed on the manufacturers’ product package inserts.

Safety Alert

Safety Alert

All injectable vaccines (such as those for shingles and chicken pox) require refrigeration or freezing. Insulins and select eye drops are also required to be shipped and stored under refrigeration.

Shelf Maintenance and Rotating Stock

As the new products are added to the retail and storage shelves, check the expiration dates of the stock, and rearrange them for the oldest to be in the front (with shortest expiration dates) for quickest access and sale. This repositioning is known as rotating the stock. Products close to expiration dates need to be removed. Each pharmacy has a policy for an acceptable range of expiration dates. A typical requirement might be that products have expiration dates of at least 12 months from the date of wholesaler receipt, and products on the shelves must have a 4- to 6-month shelf life.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

It is good customer service for technicians to call customers when the remainder of an out-of-stock or partial fill medication is available for pickup.

Handling Out-of-Stock and Partially Filled Medications

After receiving, posting, and shelving of the inventory is complete, it is important to initiate the prescription filling process for any OOS or partial fill prescriptions from the day before. A partial fill prescription is issued when the pharmacy doesn’t have a full quantity of a specific drug on hand. They will supply patients with a limited amount—usually a few days’ worth—until the drug is back in stock. The prescription order is then processed, verified, and filled so that it can be available for the patient to pick up later that same day, as promised. If possible, notify the patient when the prescription is ready for pickup. The completion of partial fill orders also takes priority after postings are complete. Insurance is commonly billed and the patient pays the copay for the entire amount at the time of the partial fill. When the order arrives and the prescription is filled for the remainder (less the partial fill quantity), the patient owes no additional payment.

Drug Recalls, Returns, and Credits

At times, drugs must be returned to the wholesaler for credit—in their original stock bottles or unit-of-use packaging and in their original condition. These returns can be because of pharmacy overstocks, patient decline of expensive medication pickup, soon-to-be-expired drugs, recalls by the manufacturer or FDA, reformulated drugs, drugs in out-of-date packaging, or drugs that are no longer manufactured. The different reasons for returns result in slightly different ways to handle them.

Drug Recalls

When an official alert for the drug occurs, known as a drug recall, the wholesaler typically emails or mails the drug recall information: drug name, dose, NDC, lot number, expiration date, etc., as well as the date and type of recall (voluntary, mandatory). Three classes of response levels of recalls exist, with Class I being the most urgent. The FDA staff determines the class that is appropriate based on manufacturer actions, the healthcare situation, and customer data from MedWatch and other sources. Table 9.5 describes the three levels of drug recalls.

For all drug recalls, the technician must check drug inventory and the retail shelves for each recalled item, pull it from inventory right away to protect the patient, and notify the pharmacist, who signs a recall form. This form is then returned to the wholesaler with any recalled drug stock items. The pharmacist should designate the appropriate plan to notify the patients who have received recalled drugs—notification in Class I is required; notifications for Class II and III are up to the pharmacist’s/prescriber’s judgment. Cash register and insurance transactions reports are essential for tracking down the customers who purchased the recalled items and talking to them about the recall. If they have specific questions about what to do to counteract any problems, the pharmacist should do the counseling.

Table 9.5 Recall Classes for Drugs

Class |

Risk |

Action Response |

|---|---|---|

I |

Urgent, immediate danger—A reasonable probability exists that the product will cause or lead to serious harm or even death. |

All patients who have received or purchased this product should be notified. |

II |

Moderate danger—A probability exists that the product could cause adverse health events, but the events would be medically reversible or temporary. |

Pharmacists and/or prescribers must decide the best practice about notifying patients. |

III |

Least danger—The product will probably not cause an adverse health event, but there is a product quality problem. |

Pharmacists and/or prescribers must decide the best practice about notifying patients. |

The role of the FDA is to monitor drug recalls and assess the adequacy of the manufacturers’ actions. After a recall is completed, the FDA makes sure that the product is destroyed or suitably “reconditioned” (recategorized with new conditions for sale). It also investigates why the product was defective and the actions to take. The FDA posts weekly reports on drug recalls that pharmacists should read. These are posted at https://PharmPractice7e.ParadigmEducation.com/SafetyReport1.

In an effort to prevent problems even before drugs are officially classified, the FDA also posts two pages of drugs pending recall classification. One is for human drug product recalls pending classification at https://PharmPractice7e.ParadigmEducation.com/SafetyReport2. The other is non-blood product ongoing recalls, which can be accessed at https://PharmPractice7e.ParadigmEducation.com/SafetyReport3. These sites should also be checked regularly to keep patients informed.

At times, pharmacists and technicians may see that the drug has been recalled or is pending classification. The product should be pulled from the inventory. The manufacturer should be notified that a return and credit are desired. Consumers can also return a recalled drug for refund or credit, per pharmacy or drug wholesaler policy.

Return of Declined Medications

At times, patients do not pick up their filled medication within seven days, even after reminder calls and phone messages. Consequently, as the technician, you must “reverse” or cancel the online insurance billing, store the prescription order in the patient profile for possible future use, and return the stock to drug inventory. For example, if a patient declines to pick up the expensive diabetic drug dulaglutide (Trulicity), you can store it in the refrigerator and then return it to the wholesaler for credit, provided that the box is unopened, and that the prescription label (perhaps attached by rubber band) can be removed without altering the packaging label.

A return-for-credit form must be completed that lists the drug(s) and quantities to be returned for credit. You and the wholesale driver must verify the contents of the return totes or boxes, and sign for the credit. Your signature guarantees that the product was purchased directly from the wholesaler. Your signature also states, under penalty of perjury, that the drugs have been stored and handled in accordance with manufacturers’ guidelines and all federal, state, and local laws. The containers are then sealed and returned to the wholesaler for credit. The signed form is filed for future reference if necessary.

Expired Medications

Pharmacy technicians must also check drug inventory (including OTC drugs and dietary supplements) for expired medications on a monthly basis, or per store policy. Remove all expired or near-expired (within three to six months) products from stock and return them to the wholesaler for partial credit. If a drug is past its expiration date, it can be returned to the wholesaler, but no credit will be issued. This process of drug returns and credits often involves a lot of paperwork and is time-consuming. However, it is another important part of inventory management and business profitability.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

Prescription vials returned by the patient cannot be returned to stock once they leave the pharmacy premises, even if they are unopened.

Wrongly Filled Prescriptions

At times, the wrong medication is filled in a prescription, which occasionally happens despite safety checks, especially when both generic and brand name drugs exist, and there is a mark of DAW1, or dispense as written, by the prescriber or DAW2, by the patient. Consider the following scenario: a patient or prescriber requests Synthroid (a brand name drug) to be dispensed, and the pharmacy inadvertently dispenses levothyroxine (the generic form of the drug). If the drug did not leave the pharmacy, the prescription can be corrected and the drug can be returned to stock.

Synthesized thyroid hormone is available as an often-requested brand name drug (Synthroid) or as a generic drug (lexovthyroxine). Before dispensing the generic, make sure there are no DAW requests from the prescriber or patient so that the correct drug is dispensed.

However, if the patient left the pharmacy, discovered the mix-up, and then came back to the pharmacy later with the medication unopened, the generic drug can be returned for money back to the patient and the correct medication dispensed, but the generic must be discarded per law and pharmacy protocol. The pharmacy cannot recover the cost of the incorrect prescription.

This symbol on the outside packaging quickly identifies that this is a Schedule C-II drug.

Handling Controlled Substances

Controlled substances demand special purchasing, receiving, and record keeping of inventory, according to the Controlled Substances Act. Each pharmacy must register with the DEA to purchase and dispense controlled substances, and the FDA requires that all controlled-substance containers be clearly marked with their “schedule” on the product label. In light of that, you should inspect containers for the schedule mark, which is an uppercase Roman numeral preceded by a C symbol (or not preceded by it): II or C-II; III or C-III; IV or C-IV; and V or C-V. The symbol C and/or the Roman numeral must be at least twice the size of the largest letters printed on the label. If a bottle is too small to display the symbol or numerals, the box and package insert must contain them. Symbols and/or numerals are not required on the patient containers.

Schedule III, IV, and V Drugs

In most pharmacies, the technician can order Schedule III–V medications. However, per store policy, the pharmacist may have to verify and sign for their receipt at delivery. After comparing the invoice with the ordered drug name, dosage, and quantity, the receipt can often be signed by the technician and verified by the pharmacist. These drugs can then be stored by the technician among the rest of the drug stock, usually alphabetically by generic drug name. All Schedule III, IV, and V prescriptions and records, including purchasing invoices, are commonly kept separate from other records and must also be kept in a readily retrievable form.

Pharm Fact

Pharm Fact

The DEA 222 form documents the ordering request to the manufacturer or wholesaler; the shipment receipt documents the pharmacy delivery; and the prescription receipt documents the dispensing to the patient.

Schedule II Purchasing

Schedule II controlled substances follow stricter protocols per DEA law and regulations. Similar to other medications, PAR levels for most C-II drugs generate automated inventory alerts in the pharmacy software for reorders or special out-of-stock or partial-fill orders. However, purchase of Schedule II controlled substances must be specifically initiated and authorized by a pharmacist and executed on a DEA 222 form, either online or on paper (see Figure 9.2).

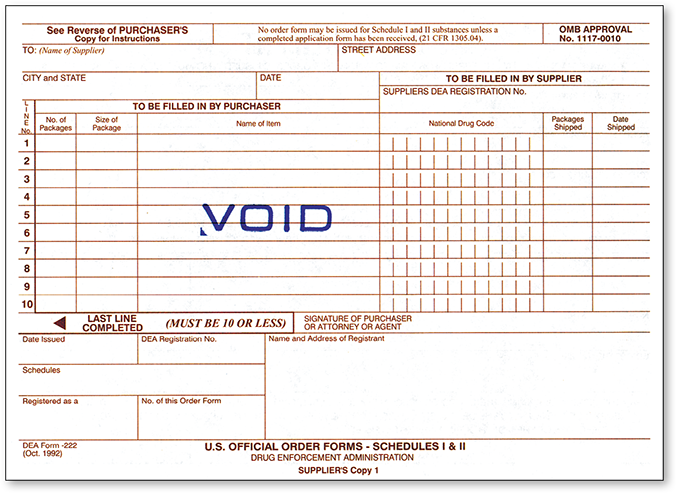

Figure 9.2 DEA 222 Form

The DEA form must be completed online or on paper by the pharmacist for Schedule II drug purchasing.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

The theft or loss of C-II drugs requires the pharmacist to complete a DEA 106 form and submit it to the DEA.

To order online, each pharmacy has a DEA registration number, and each of its pharmacists has a secure pharmacy user name and password protection. Online access to ordering allows next-day delivery in most cases. If Schedule II drugs are borrowed from another pharmacy, the pharmacist has to complete and sign a hard copy of a DEA 222 form.

Schedule II Receiving and Documentation When receiving the sealed totes of Schedule II drugs, the technician should check that the seal is not broken. The pharmacist must then personally break the seal on the tote and verify the contents with the invoice. After verification, the pharmacist must document the following information on the DEA 222 delivery receipt section: the date, the name and amount of Schedule II drugs received, and the corresponding NDC numbers. You, as the technician, can then post the Schedule II drug inventory to the database, including the NDC numbers, prices, and expiration dates.

Controlled Substance Disposal As Schedule II substances in the inventory expire or are defective (such as a case of broken tablets), they must be disposed of properly. Any controlled drug disposal must be itemized, recorded, witnessed, and signed by a second pharmacist. In most cases, Schedule II drugs are saved for destruction until the next visit of the state drug inspector, or they are returned to an authorized destruction depot after proper documentation has been completed and filed. (The proper disposal of other drugs, needles, and materials will be addressed in Chapter 14 on medication safety.)

The DEA also allows community pharmacies to conduct take-back programs as a customer service. These programs allow patients to bring in (or mail in) their unused, unwanted, or expired prescribed controlled substances (not illegal substances) to a pharmacy-maintained collection receptacle. (Take-back programs are also covered more in Chapter 14.) The receptacle must be stored in the locked portion of the pharmacy with the controlled substances, where an employee is always present. Community pharmacies may also maintain take-back control substance receptacles at long-term care facilities they service if there is a locked, staffed area.

The seal on totes for controlled substances must arrive undisturbed and must be broken only by a pharmacist.

Schedule II Perpetual Inventory Record As you have seen, the inventory of controlled substances must be documented at every step in the process, from purchasing through storage, dispensing, and disposal. (Dispensing documentation will be explained in Chapter 14.) The precise count of each and every capsule, tablet, patch, liquid, injection, and other forms must be accounted for at all times. Because of this, there are special policies, procedures, and schedules for counting the inventory of controlled drug substances. Community pharmacies use automated or manual perpetual inventory to maintain inventory and close control of all Schedule II drug stock.

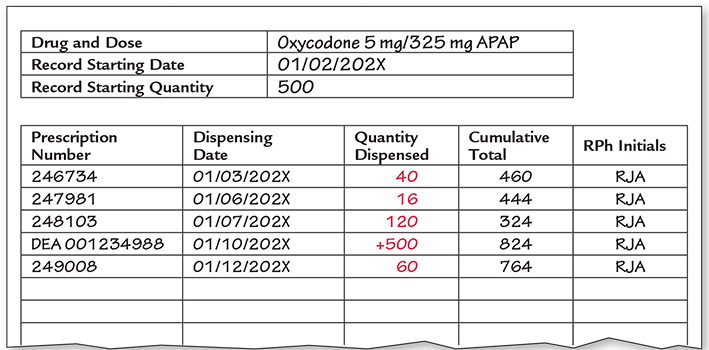

A perpetual inventory record is a method of accounting for all Schedule II medications on a tablet-by-tablet (or other dosage form) basis. Figure 9.3 shows an example of a printed perpetual inventory record, which documents each and every dosage of Schedule II drugs received and dispensed. This record includes product, dosage, quantity, date received or dispensed, prescription number, remaining inventory, and signature or initials of the pharmacist. Community pharmacies typically use an automated perpetual inventory system.

Biennial Inventory Count In addition, a biennial (every two years) inventory of Schedule II drugs must be taken. Some states (and pharmacies) have even more stringent requirements, such as a yearly inventory. These inventories should closely approximate the perpetual inventory record. For Schedules III, IV, and V substances, an estimated count and/or measure is permitted, unless a container holds more than 1,000 capsules or tablets. If the container has been opened, an exact count is required.

Figure 9.3 Perpetual Inventory Record

Some pharmacies use red ink pens for quantities removed from inventory for dispensing, and black ink pens for amounts of inventory received or maintained.

The Schedule II inventory count should not vary by more than four days from the biennial inventory date. The copy of the inventory must be sent online to the DEA, or the original hard copy must be sent by mail. Major deviations on Schedule II drug inventory must be investigated and reported if not resolved.

Pharm Fact

Pharm Fact

Whenever a pharmacy is in the process of being sold, an inventory count is required, and the value of the drug stock is included in the purchase price.

Additional tracking mechanisms exist by state and federal authorities to monitor the distribution of Schedule II drugs. If there is evidence of overprescribing by a physician, overdispensing by a pharmacy, or overselling of Schedule II drugs by a wholesaler, the DEA—after a thorough investigation—has the authority to temporarily or permanently revoke the DEA license of that physician, pharmacy, or wholesaler. A wholesaler can limit the monthly amount of controlled substances distributed to a community pharmacy if it deems that there has been excessive use.

Estimating Overall Drug Inventory Value and Turnover

Once each year, each item in stock must be counted, and the task is often assigned to a senior pharmacy technician, or it is outsourced. The inventory survey is used to determine the inventory value (cost) and turnover rate and to make any necessary adjustments in stock levels. Many pharmacies aim for an inventory turnover rate of approximately 10–12 times a year. If the inventory of a specific drug or product turns over every other month, the turnover rate is 6. If the inventory turns over every month, the rate is 12.

An experienced technician is responsible for ordering and stocking not only the drug product inventory, but necessary medical supplies and supplements as well.

From the information gleaned from the inventory assessment, several important inventory decisions must be made:

How much of each drug and product should be maintained?

When should inventory levels be adjusted?

Where should inventory be stored?

Factors that need to be considered for these decisions encompass the individual pharmacy’s track record of product turnover, the new drugs being released that will need to be added, floor space allocation, design and arrangement of shelves, and demands on available refrigerator or freezer space. Adjustments may include returning a portion of the drug stock to a wholesaler, selling or transferring stock to another pharmacy, and lowering automatic restock levels.

Because inventory information takes time to get to know well, technicians need experience working with the various aspects of inventory management before they move into positions of such responsibility. By watching the sales reports and inventory trends, a technician can begin to know enough to assist the pharmacist in suggesting the most appropriate minimum and maximum inventory levels to be set in the inventory control software.