11.3 Electronic Hospital Records and Medication Orders

Taking advantage of the digital age, hospitals now utilize hospital management software systems that collect patient data and communicate between medical departments, billing, and finance, and with external healthcare providers. These overall management systems need to interface well with each department’s specific software, technology, and records, such as that in the pharmacy department. Some common hospital management software systems include Cerner, Epic, Net Health Systems, Pro Med, and eHospital Systems. This capacity for interoperability—interactive communication and operation between internal record programs, software and hardware systems, and external information sources—is one of the greatest advantages of a system based on electronic health records (EHRs).

Some of the key forms of EHRs pertinent to the pharmacy include intake records and patient medical/medication histories, bar code point-of-care scanning information, electronic medical charts, medication orders, and electronic medication administration records. The EHR software provides the following benefits to members of the healthcare team:

immediate access to a patient’s medical record and hospital medication profile

streamlined workflow processes

improved documentation

enhanced coordination of patient care

clear communication with other healthcare personnel

data collection and trend tracking information to measure safety to meet hospital accreditation standards

Intake Records

Upon admission to the hospital, the patient or guardian must be interviewed about the patient’s medical and medication history to assemble an accurate intake record. The record also includes key personal, insurance, and billing information and the doctor’s admitting diagnosis. Collecting this information is often done by an admitting staff person or a nurse who inputs the information into the hospital computer system.

A patient’s wristband with its bar code helps the healthcare team follow a specific patient’s care plan and keep the patient’s EHR up to date with each medication administration and procedure.

Patient Wrist Bands

To follow a patient through the hospital system and keep the EHR complete, all patients receive a wristband that has their name, birth date, and a bar code at intake to the general hospital or emergency department. As nurses in the care units enter a shift, it is common practice for them to introduce themselves and ask the patient for name and date of birth (if it is possible for the patient to respond). The nurse then verifies the patient’s identity by scanning the bar code on the wristband prior to each medication administration.

Medication Histories

As with the community pharmacy, accurately documenting the medication history of new patients is often time-consuming and frustrating. It can be especially problematic for an admitting nurse who is not as knowledgeable about brand and generic drug names and indications. Problems arise with patient memory, confusion, and understanding of questions; limited access to patient records; time constraints; and language or cultural problems. More and more hospitals are working with Surescripts and its record locator and exchange service to access more of a patient’s medical history and medication records from external physicians and pharmacists, even if out of state.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

When discussing medication history with a patient, keep your voice low to avoid being overheard to protect the patient’s privacy per HIPAA regulations.

Patients may also bring in home medications (home meds) or those medications prescribed to them prior to admittance. These labeled and unlabeled bottles of medications from home must be identified and added to the medication history. If patients know they are taking a medication but the bottles are not available, the admitting staff person needs to call the community pharmacy or the prescriber to get the drug, dose, and schedule. That is why some hospitals are assigning experienced and specially trained pharmacy technicians to identify the home meds and assist in assembling the medication information in the initial admitting process.

This pharmacy technician is interviewing a patient about his medication and allergy history.

As in a community pharmacy or doctor’s office, the patient (or guardian) will need to be shown a privacy protection statement and sign it, as is necessitated by HIPAA regulations.

IN THE REAL WORLD

IN THE REAL WORLD

At North Memorial Hospital in Tucson, Arizona, a number of experienced technicians and pharmacy interns were selected for specialized training in obtaining patient medication histories and seeking additional intake information when information was missing or medication problems surfaced. They would contact the patient as well as the patient’s family, healthcare providers, and community pharmacy. The technicians and interns had a dedicated work space and had been drilled in common critical medications that should not be stopped during a hospital stay, proper medication dosages, and dangerous drug interactions.

Over the two years of the pilot project, the new medication reconciliation process found over 1,240 patients needed continuation of at least one critical medication (particularly thyroid drugs, anticonvulsants, and antidepressants) that would otherwise have been missed. The recommendations of the technicians and interns alerted the pharmacists, who made suggestions to the prescribers for modifications in the drug therapies. For example, over two months in 2010, the pharmacists made 178 interventions for 132 patients. The prescribing physicians accepted 102 (57%) of these recommendations, showing the value of these technician- and intern-prompted alerts. After the study was over, North Memorial continued and expanded the program. Better outcomes resulted, and nursing, physician, and pharmacist staff time was freed up for other tasks.

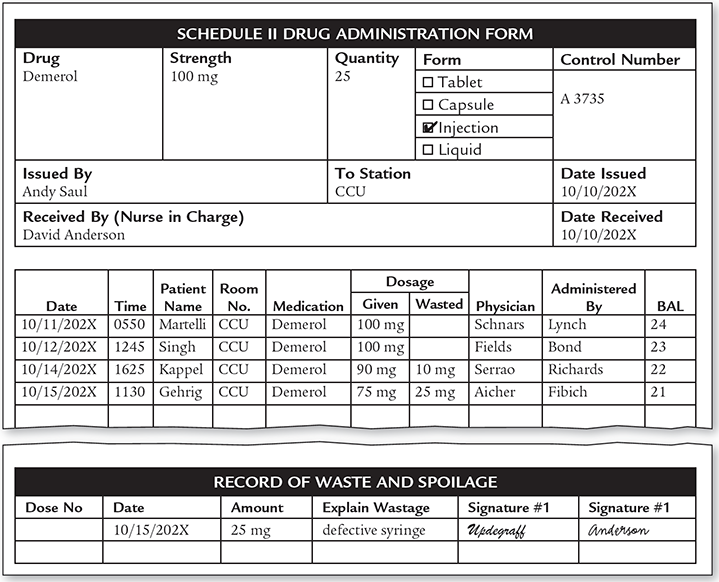

Admitting Orders

After intake, the nurse electronically transmits the admitting order to the pharmacy department. An admitting order is a request for specific medications and medical procedures (see Figure 11.1) that was written in the emergency department or in a patient’s room by the physician who met with the patient and is admitting them. This order may contain a suspected diagnosis and requests for lab tests or radiology examinations; nursing staff instructions; dietary requirements; as well as medication orders with the allergy and medication history.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

All information collected using automation must be used in a way that protects patient privacy, according to HIPAA.

A pharmacist, pharmacy resident, or pharmacy intern then must review the compiled medication history and home medication drug list to ensure that no critical medications have been discontinued or missed and that there are no problematic allergies or interactions. If not involved earlier, a specially trained pharmacy technician may be assigned to check the medication and allergy history and home medication list for completeness and accuracy, doing follow-up calls and even visiting the patient to ask questions to fill in any incomplete information.

Once the medication history information is complete and accurate and the admitting medication orders are submitted, a drug utilization review (DUR) will be run, and the software will highlight allergy and drug interaction problems as it does in the community pharmacy. The pharmacist will assess any medication-related issues and provide the admitting physician with recommendations or counsel about the admission medication order.

Figure 11.1 Admitting Order

Whether a written or digital admission order, these are common required informational elements.

IN THE REAL WORLD

IN THE REAL WORLD

In 2011 in Joplin, Missouri, St. John Hospital (known today as Mercy Hospital Joplin) converted its medical records from paper to EHRs with digital storage. Three weeks after completion, a tornado with 200-mph winds ripped through Joplin, destroying the hospital and throwing its paperwork to the sky. Because of the transition to an EHR system, the hospital was able to recover its patient records after electricity was restored. Questions remain about how to handle access to records when electricity or internet access has not yet been restored. Hospitals and hospital pharmacies have to do various kinds of emergency disaster planning to handle the contingencies of many different types of threats and hazards from tornadoes, floods, hurricanes, and fires—to acts of terrorism, shooters, and infectious diseases.

The medications patients brought from home or which were prescribed before arriving at the hospital may not be on the hospital’s approved drug formulary. Even so, the physician may decide that it is in the patient’s best health interest to continue these nonformulary drugs, and, to do so, the physician will write “continue home meds” on the admission order.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

Nurses cannot dispense home medications unless a hospital prescriber writes a medication order allowing this. Then the medication needs to be brought to the hospital pharmacy for a label and bar code to allow the nurse to scan before administration.

If approved by the pharmacist, the home meds may be sent to the pharmacy to be distributed through the hospital unit dose delivery system or, depending on hospital policy, may be kept at the patient’s bedside for self-administration. To do this, the patient’s physician must write an order for “Bedside medications,” which alerts the pharmacy personnel and the nursing staff to allow the administration. At discharge, the patient brings along any remaining “at bedside” medications.

Electronic Medical Charts

In the hospital rooms of the past, at the patient’s bedside was a medical chart—hand-written charted notes on observations and vital signs at different times, medication administrations, physician diagnoses and recommendations, and other documentation held together on a clipboard. But now, the medical chart is digitally transportable and interactive, holding all this information plus the full EHR along with the medication history and list. For example, McKesson has a ProMedica Electronic Charting System (iCare), and Epic has the EpicCare Inpatient Clinical System. Both of these allow electronic communication to all departments in the hospital and include the patient’s personal identifying demographics, daily physician and specialist notes, nursing assessments, medication and lab orders, tests, dietary necessities, problem list, and, eventually, discharge summary.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

All pharmacy personnel are trained to identify random medications and unlabeled drugs brought in by patients.

As the nurse and provider continually add notations to the digital medical chart, the patient’s real-time bedside information is shared with everyone on the patient’s hospital healthcare team, including the pharmacist. For pharmacists, these charts provide easy access to current patient care information to provide better medication therapy management. For instance, the pharmacist may call up lab results to monitor the patient’s drug blood levels for efficacy or toxicity before allowing a medication refill or dosage change.

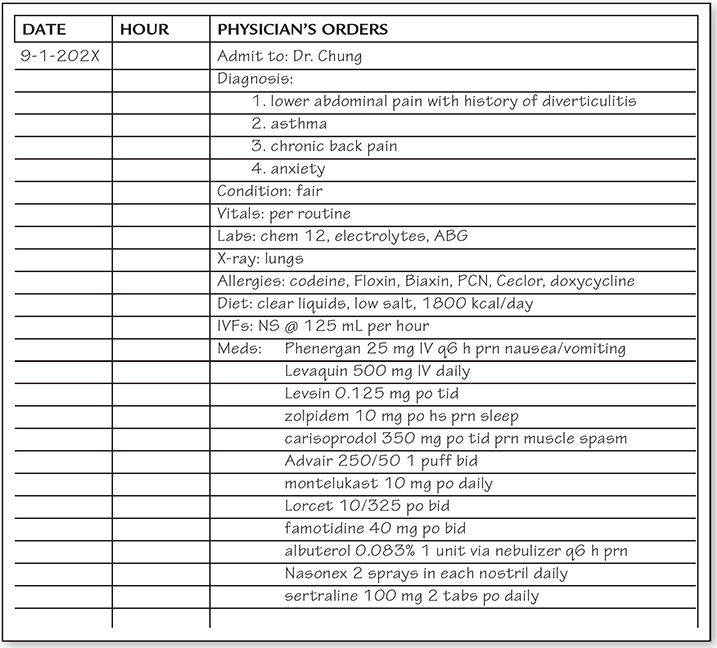

Medication Orders

As with the admission medication order, any request by the physician for drugs for a patient comes to the hospital pharmacy as a medication order (an official hospital prescribed drug request). A medical order often includes much more information than a community pharmacy prescription: the individual patient’s diagnosis, allergies, diet, activity level, vital signs, requested radiology images and laboratory tests, and medications (both routine scheduled and oral drugs as well as parenteral medications and IV fluids), among other pertinent information.

St. John’s Hospital (known today as Mercy Hospital Joplin) in Missouri was able to recover its EHRs after the devastating tornado on May 22, 2011.

Types of Medication Orders

Besides the initial admitting order, there are several other kinds of medication orders:

Daily Order After the physician checks on the patient each day, a daily order is placed for any new medications that have not been requested through the admitting (or home med continuation) order. The daily order may also modify those earlier orders, such as providing a change in dose or schedule based on how the patient is responding.

Continuation Order If the physician checks on the patient the next day or later in the week and wants to continue the same daily drug regime, they submit a continuation order. Most hospitals have a policy that the physician must review, approve, and electronically resubmit (or rewrite) all daily medication orders at least weekly to decide whether or not a continuation order is the best therapy. Continuation orders of antibiotics for patients fighting an aggressive infection are often checked and renewed on a more frequent than weekly basis, or per hospital policy, to prevent unnecessary use. Continuation orders are also sent to the pharmacy for patients who transfer from one unit of the hospital to another (e.g., from surgery to medicine).

Standing Order A standing order is a standard medication order for each patient who receives a common treatment or surgery in which the same set of medications and treatments applies. For instance, there will be a standing medication order for every patient who goes through a typical appendectomy without complications. The physician simply pulls up the screen with the appropriate standing order in that hospital for the appendectomy (or any surgery or specific treatment) and modifies it as needed to fit the patient before transmitting the standing order to the hospital pharmacy. Postoperative (postop) orders written after surgeries are also common examples of standing orders.

Stat Order A stat order is an emergency order typically sent electronically or telephoned to the pharmacy. These orders must receive priority attention and be immediately input, digitally verified, and filled without delay. After final pharmacist verification, the pharmacist or technician delivers the medication in person as soon as possible for the nurse to administer.

With an EHR-based system, prescribers, nurses, pharmacists, and other hospital healthcare specialists can access patient medical records and send medical orders electronically via computerized prescriber order entry (CPOE) to the pharmacy from their handheld devices or unit/room computers.

Discharge Order A discharge order is an order that provides take-home instructions for a patient who is leaving the hospital. This order includes all prescribed medications and dosages. Prescriptions are commonly written for a seven-day or one-month period until the patient’s follow-up visit with the primary care physician or specialist.

In receiving and filling these medication orders and working with the patients’ EHRs, it is important to remember that you must be on guard to protect the patient’s privacy. That means no discussion of patient information with others for unauthorized reasons or with unauthorized persons, or where others can hear (such as in the dining room or elevator); no discussion of confidential information outside the hospital and no removal of files; no leaving up on the screen any information that is private or allowing staff without legitimate reasons or authority to look over someone’s shoulder at a screen, medication list, or order. These are just some of the provisions of the HIPAA legislation that is part of the practice in handling medication histories and orders. These are laid out in the hospital pharmacy’s P&P Manual.

Portable Computerized Prescriber Order Entry

Most hospital medical orders are electronically sent to the pharmacy via a computerized prescriber order entry (CPOE) from the physician’s mobile device or hospital room computer. The CPOE software can even allow hospital prescribers who are off-shift to order medications from their home or private office. CPOEs reduce ordering and transcription medication errors from the misinterpretation of a prescriber’s handwriting (the number one preventable error). CPOEs have also simplified the posting of patient hospital charges and inventory ordering.

Pharm Fact

Pharm Fact

By 2018, 65% of hospitals already adopted CPOE (at a minimum 85% of medication orders) according to the Leapfrog Hospital 2018 Survey. Government financial incentives have accelerated the adoption process.

Hospital adoption of CPOEs, however, has been delayed in some facilities due to high costs for initial implementation and maintenance, insufficient time and costs for training staff, resistance by prescribers to embrace change, and the complexities of converting existing department-specific software to hospital-wide software.

Pharmacy Input of Handwritten Orders

Not all orders are delivered to the pharmacy via electronic transmission, especially in hospitals that have not completed full implementation of an EHR system. Handwritten orders may be delivered to the pharmacy via personal delivery, fax, phone order, or a pneumatic tube (like at the bank) from the prescriber or nursing unit. However, these handwritten hospital orders must then be entered by a pharmacist into the hospital/pharmacy software or by a technician who will have it verified by the pharmacist.

Electronic Medication Administration Records

The electronic tracking of drug therapies continues through the hospital software system. Once the pharmacy delivers a medication for administration, the nurse scans the patient’s bar-coded wristband and accesses the patient’s EHR from a computer or a notebook in the patient’s room or on a mobile cart. The nurse verifies the medication order and compares the scanned bar code to the scanned bar code on the medication label and EHR. Using this bar code point-of-care (BPOC) scanning reduces the potential for medication errors because of the software’s embedded safeguards.

Using BPOC technology, the nurse can verify that the right drug at the right dose and by the right route gets to the right patient at the right time.

The scanning process enters an electronic medication administration record (eMAR) into the patient’s EHR medical chart. The eMAR system automatically records and documents the name of the drug, dose, route of administration, administration time, and start and stop date, plus any special instructions for the nursing staff. This BPOC scanning and eMAR documentation must occur for all medication orders, including oral and IV drugs. Because of BPOC technology, medication reconciliation can occur once more at the bedside, sending any safety alerts to the nurse before the medication is administered (see Figure 11.2).

Figure 11.2 Printout of an Electronic Medication Administration Record (eMAR)