12.1 Types of Microorganisms

As explained in an earlier chapter, 17th century European scientists discovered the existence of microorganisms that cause infection, launching the field of microbiology, or the study of microorganisms. Understanding how these microbes function is key to infection control because harmful microorganisms, especially bacteria, are everywhere. Microorganisms are mainly single-celled living organisms that are classified according by type—bacterium, virus, fungus, or protozoan—as well as by effect: pathogenic versus nonpathogenic.

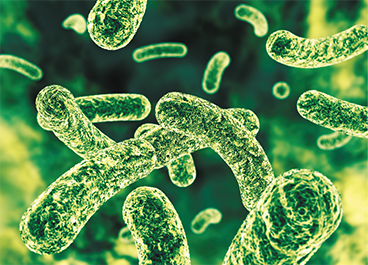

In 1873, using the first microscope (which he made himself), Anton van Leeuwenhoek first saw moving shapes like these bacteria, and understood that they were independent organisms living within humans.

Bacteria

A bacterium is a type of small, single-celled microorganism. Bacteria exist in three main forms as categorized by the shapes viewed under the microscope, (see Figure 12.1): spherical (such as cocci), rod-shaped (such as bacilli), and spiral-shaped (such as spirochetes). Bacteria are responsible for causing a wide variety of illnesses, such as food poisoning, strep throat, ear infections, rheu- matic fever, meningitis, pneumonia, tuberculosis, and conjunctivitis. Normal human skin is colonized by several kinds of bacteria, some of which are potentially harmful, or pathogenic, and others that are beneficial or neutral, or nonpathogenic. Bacteria are easily passed off to others by touching, coughing, sneezing, brushing hair, kissing, and exchanging fluids.

Figure 12.1 Characteristic Bacterial Shapes

Viruses

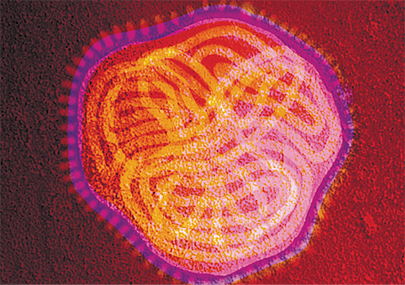

A virus is a microorganism that consists of genetic material enclosed by a casing of protein. Viruses need a living host in which to reproduce, and after replicating, these organisms cause a wide variety of illnesses and diseases, including influenza (flu), colds, polio, mumps, measles, chicken pox, shingles, hepatitis, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). They are passed on in similar ways to bacteria and other parasites. For instance, the pandemic-causing Zika virus is transmitted mainly via the mosquito.

A virus is much smaller than a bacterium and can be viewed only with an electron microscope, as seen here. The virus does not have all of the components of a cell and requires a living host to replicate itself.

Fungi

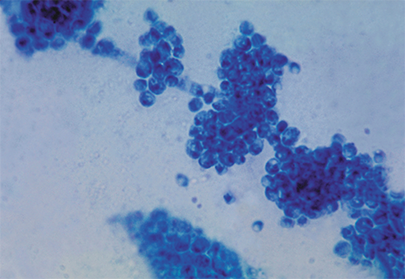

A fungus lives on organisms by feeding on living or dead organic material. Fungi reproduce slowly by means of spores. Spores are microscopic reproductive bodies that travel through the air and can develop into molds, mildews, mushrooms, or yeasts. Some molds are the source of antibiotics, such as penicillin. Other fungi cause skin conditions such as athlete’s foot and ringworm or vaginal yeast infections. In more serious cases, systemic fungal infections can form in the lungs and other areas deep within the body, which can be potentially life-threatening. The air and surfaces of objects have fungus living on them, emitting fungal spores into the air for dispersal.

This photomicrograph of the fungus Candida albicans indicates its multicellular structure.

Protozoa

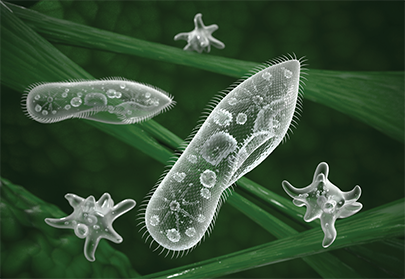

A protozoan is a microscopic organism made up of a single cell or a group of identical single cells. Protozoa live in water or as parasites inside other creatures. Examples of protozoa include paramecia and amoebas. Amoebic dysentery, malaria, and sleeping sickness are examples of illnesses caused by protozoa.

Paramecia and amoebae are protozoa commonly found in freshwater lakes.

Effects of Microorganisms

As mentioned earlier, microorganisms can be either nonpathogenic (harmless or beneficial) or pathogenic (harmful).

Nonpathogenic Microorganisms

The majority of microorganisms are nonpathogenic, meaning they are not dangerous, and besides not being harmful, many actually perform essential functions, such as keeping pathogenic populations down or helping the body break down various food substances. Outside the body, they can create by-products that are used to formulate medicines, ferment wine, fix nitrogen in the soil, and other important functions. For example, yogurt consists of “good” bacteria that can reestablish the positive bacteria typically found in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract after a course of antibiotics that kills them. The beneficial bacteria can also reduce the incidence of diarrhea and yeast infections from antibiotics.

Pathogenic Microorganisms

Pathogenic microorganisms, as noted, have led to widespread illness and disease throughout the world. Some of these microorganisms have been the catalysts of epidemics (regional contagious disease outbreaks) and pandemics (worldwide contagious disease outbreaks, such as the Spanish flu in 1918). Public health diseases and ongoing epidemics kill thousands of people annually in different locations in the world by different local organisms (such as Ebola, tuberculosis, swine flu, bubonic plague, yellow fever, malaria, cholera, and others).

IN THE REAL WORLD

IN THE REAL WORLD

Throughout history, many pandemics have killed millions of people. The HIV/AIDS pandemic is well known and feared, especially now in countries in sub-Saharan Africa, such as South Africa, where 13.1% of people live with the disease (according to a 2018 South African report). Some other notable pandemics include:

Zika–a virus that is passed by certain mosquito species. It has been active in Africa and Asia from the 1940s on, but since 2007 it has been rapidly spreading in South, Central, and North America and the Caribbean, causing neurological damage in those infected and a high risk of birth defects in the children of women infected while pregnant.

Ebola–a virus that causes victims to essentially bleed to death internally. The latest major outbreak of the virus ravaged West Africa and killed over 8,000 people.

Spanish flu–or influenza, a disease caused by the H1N1 virus. This 1918 pandemic was spread around the world after World War I and killed approximately 50 million people worldwide, including an estimated 675,000 people in the United States. It has been called the worst pandemic in human history.

Cholera–an illness caused by bacteria that is spread through contaminated food or water. There have been seven pandemics of cholera since the 19th century, killing millions of individuals on five continents.

Polio–a pandemic in the first half of the 20th century. It has killed or crippled millions, and continues to do so at a slower rate.

Bubonic plague–a disease caused by bacteria and spread by the fleas of diseased black rats. This pandemic killed 25 million people throughout Europe and Asia during the 14th century.

Smallpox–caused by strains of a virus. It was a virulent killer for centuries, responsible for the deaths of more than 300 million people in the 20th century alone.

Though these organisms (other than smallpox) continue to wreak havoc in many people’s lives in various places in the world, the presence of vaccinations and/or other public health efforts have prevented them from causing the regional and worldwide harm they once did. Scientists are working to contain and prevent the spread and damage of the Zika virus. However, as microorganisms build up resistance to antimicrobials, there is fear of their resurgence to create epidemics and pandemics again.

During the bubonic plague of the 14th century, doctors worked in full-body garb to protect themselves from the disease. This was an early hazmat suit, so to speak. The beak of the mask held pungent herbs to purify the “bad air,” and included a full-length heavy robe covered in wax, leather breeches, and leather gloves and boots.

Antimicrobial Resistance

Many antimicrobial medications—the antibiotics, antivirals, and antifungals—are effective in killing or neutralizing pathogenic microorganisms in humans. However, microorganisms adapt rapidly and can become resistant to both some sterility techniques and medications. A medication can kill the majority of a colony, or community of microorganisms, so that the disease symptoms decline or go away. However, a remnant of the microorganism colony may remain that was either immune or only weakened by the medication. These remaining microorganisms can reproduce a new strain that is resistant to the medication.

This growth in microbial resistance is even more likely to occur when patients do not complete their prescribed therapy regimens of antibiotics and antivirals, stopping when disease symptoms go away. Also, the overprescribing of antibiotics by providers for unnecessary reasons (like prescribing an antibiotic for a viral illness) or incorrect administration by patients can result in ever more virulent microorganisms. In particular, noncompliance with HIV therapy is leading to rapid viral resistance.

Microbial Resistance and Superbugs

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria have led to the rise of superbugs, microorganisms that are immune or highly resistant to conventional antibiotic therapies. These superbugs are a growing worldwide healthcare concern both inside and outside of the hospital. One in five urinary tract infections, is resistant to most sulfa drugs. Antibiotic-resistant strains of tuberculosis kill 65,000 people each year worldwide. Many strains of salmonella, a common cause of food poisoning, are resistant. Many sexually transmitted infections, such as gonorrhea, are increasingly difficult to treat because of their resistance. Hospitals, which are centers for both disease and health, are places where the most virulent diseases can meet the most vulnerable individuals if strict infection control techniques are not applied.

Pharm Fact

Pharm Fact

There is a MRSA that is acquired in healthcare facilities and one that is acquired in the community. The HAI form of MRSA tends to be more virulent and deadly.

Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) are infections that patients contract while receiving care at a medical facility. They are an ongoing threat in all hospitals, requiring intense attention. HAIs result in extended, higher drug doses and multiple drug therapies, costly hospitalizations, and sometimes death. Common organisms causing HAIs include the methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteria that can cause serious bloodstream infections. MRSA is often passed by contaminated hands. Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) is a resistant bacterium that can cause potentially serious diarrhea in patients on certain antibiotic therapies; the antibiotics have killed the good bacteria in their digestive systems that generally keep C. difficile populations too low to cause harm. Particularly susceptible to these HAIs are patients who have compromised immune systems or open wounds, scratches, or devices that need frequent cleaning and changing, such as urinary catheters, ventilators, or intravenous catheters.

Pharm Fact

Pharm Fact

The deaths of Muhammed Ali and Patty Duke (Astin) from sepsis in 2016 made people more aware of the behind-the-scenes health issue it can cause.

HAIs, and any infection, can trigger sepsis, often referred to as “blood poisoning.” Sepsis arises when an infection is so threatening to the body that the immune system goes into overdrive. It begins to attack the body’s own blood vessels and organs, causing inflammation, leaky vessels, organ failure, and septic shock. Infections such as pneumonia, urinary tract infections from catheters, meningitis, a burst appendix, or even an untreated cut that becomes radically infected can lead to sepsis. According to the CDC, sepsis is more common than a heart attack and claims more lives than cancer, killing more than 258,000 US citizens each year. Yet swift recognition and finding the right antibiotic therapy and offering organ support can save lives.

IN THE REAL WORLD

IN THE REAL WORLD

According to the CDC, one out of every 25 patients hospitalized develops 5% of the cases. The CDC estimates that 2.25 million patients per year acquire a new infection while being hospitalized, which adds an additional cost of over $10 billion per year; 37,000 deaths per year are due to HAIs.

In 2015, at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, more than 100 patients were exposed to the carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) during specialized endoscopy procedures. CRE has become known as the “nightmare” bacteria because of its resistance to antibiotics. At least seven people were infected, and two died. UCLA is just one of many hospitals to have an outbreak of an HAI. In fact, a hospital in Kentucky had an outbreak of CRE that involved 23 patients between 2016 and 2017. These cases further highlight the challenges hospitals face with the growing risk of drug-resistant superbugs. Adherence to recommended infection control guidelines significantly decreases the transmission of infectious agents.