14.2 Root-Cause Analysis of Medication Errors

To prevent medication errors, one has to identify clearly what the error was, where it took place, and, through closer examination, what specifically caused it (i.e., the why). Medication errors are caused by numerous factors within the different systems of any pharmacy, from the organizational systems to the technical tools to the specific human decisions. In the 1940s, the US military developed a process of root-cause analysis that was called the Failure Mode Effects Analysis (FMEA). This analysis breaks larger processes down into levels and tasks to find the root causes of failures (problems) and the rate or probability of failure occurrences, the consequences, and ways to fix the failures. Healthcare facilities are now using modifications of this form of analysis and others for quality control and safety initiatives.

Root-cause analysis is a systematic approach to identifying the deep causes of why something happened to prevent a recurrence. Administrators use facility data on error trends to figure out gaps in policies and procedures as well as technological problems. Pharmacy directors can apply root-cause analysis within their departments for investigating common errors, and technicians can use it to examine their own practice. Numerous failures can occur at once, contributing to each other and magnifying the possibilities and quantity of errors, so prevention strategies have to address all three levels of systems and processes.

An organizational failure occurs because of a deficiency in organizational rules, leadership, culture, policies, or procedures. Examples of this type of failure include pressure for production and cutting corners over safety concerns; inadequate staffing, training, or breaks per workload; out-of-date or poor rules or procedures for preparing or admixing parenteral medicines, such as chemotherapy drugs; poor maintenance schedule of automated devices; and poor facility organization and cramped spaces.

A technical failure results from equipment problems. Examples of this type of failure include a virus in the pharmacy software throwing off the information or losing patient information; a bar coding scanner that misreads the code and scrambles the numbers; and incorrect preparation of a total parenteral solution (TPN) due to a calibration error of the automated compounding device (ACD) in the hospital pharmacy.

A human failure occurs at an individual action level. Examples include a technician pulling a medication bottle from the shelf based on memory without cross-referencing the bottle label with the prescription/medical order or without scanning the National Drug Code (NDC) bar code; anyone skipping an aseptic technique step; a pharmacist approving a medication without addressing the Drug Utilization Review (DUR) alerts or carefully checking a technician’s calculations or medication selection; a patient not paying attention to the label, not adhering to prescribed drug therapy, or quitting therapy early.

Identical label designs are a source of confusion and a cause for error when filling a prescription, especially if a technician uses memory instead of checking and double-checking the NDC number when selecting a medication.

Addressing Organizational and Technological Failures

Some issues must be addressed by the community or hospital pharmacy, not by the individual personnel.

A Safety-Oriented Work Environment

A pharmacy’s physical setting can make a major contribution to fostering disorientation or enabling attention. Adequate space and clean, well-lit conditions are just some of the basic requirements for a well-working pharmacy in addition to adequate staffing. Work shifts of 12 hours or longer (or even more than 8 hours) by pharmacy staff, physicians, and residents-in-training can correlate with a higher incidence of medication errors. Table 14.1 outlines the best practices for a pharmacy work environment that promotes safety and reduces errors.

Table 14.1 Workplace Ergonomic Practices to Promote Safety

|

A Safety-Oriented Culture

Pharmacists are responsible for adequate on-site technician training, oversight, verification of prescription stages, patient education and counseling, and prescriber discussions about resolving prescription or medication order issues.

Within the pharmacy, a safety-promoting work culture is key. Pharmacists need to create a professional, nonpunitive environment where technicians are encouraged to take responsibility, ask questions, query prescriptions and DUR alert flags, and suggest contacting prescribers. It must be clear that safety is more important than who is at fault, time goals, or productivity measurements. To continually keep the mind fresh, break times must not only be encouraged, but enforced. Time-flow management principles must be indoctrinated to avoid interruptions and distraction errors at key points of the prescription filling process.

IN THE REAL WORLD

IN THE REAL WORLD

Pharmacy understaffing of both technicians and pharmacists is a significant cause of medication errors in all settings, but especially in large-scale chain and independent pharmacies. Though staffing levels have been minimized, the number of prescriptions and vaccine administrations have increased and clinical responsibilities have been added. At the same time there has been an emphasis on working faster to increase productivity and customer satisfaction.

In 2014 and 2015, NBC’s I-Teams in Washington DC and New York City investigated claims of mounting prescription errors in the chain pharmacies of CVS and Walmart. Joe Zorek, a pharmacist for CVS for 30 years, filed a whistle-blower lawsuit against his company. “I was concerned we were going to kill someone.” Another CVS whistle-blower explained that the errors were numerous. “I would say there’s at least one a day if not more.” Both blamed the pressure put on the pharmacists and technicians to hurry and reach time and productivity quotas.

At the time, then executive director of the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy, Dr. Carmine Catizone, confirmed the concerns: “We’ve heard the complaints about the large chains and how they’re morphing or how they resemble fast food restaurants.” Some large chains have been refusing to monitor errors effectively and turn over their error reports. In 2015, the executive vice president of the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, Allen Vaida, told the New York I-Team that an estimated 30 to 50 million prescriptions annually have some type of error.

Technicians usually do not make organizational policies nor are they responsible for purchasing automation tools. But technicians can contribute by offering suggestions to the pharmacists or pharmacy administration and through organizational suggestion structures when appropriate. You can also learn how to use, maintain, and calibrate automation, alerting the pharmacists when there are breakdowns or issues.

Accountable Care Organizations A voluntary movement for quality improvement, safety, and cost reduction is the accountable care organization (ACO) movement. ACOs are formal groups of physicians, pharmacists, and other providers, hospitals, and healthcare facilities that join together in a coordinated way to seek out measurable improvements in patient health outcomes. They study reports and trends about medical errors and expenditures to set and achieve specific goals to improve services and delivery while reducing costs. The healthcare ACO providers and facilities share both the business risks and the savings of the healthcare improvement efforts. The aim is to reward healthcare professionals for good health outcomes and the quality of healthcare decisions, services, and products rather than the quantity.

Medicare is encouraging and leading the formation of ACO groups and facilities. ACO organizations can market this positive approach as a benefit to patients and insurance companies. For more information on Medicare ACOs, visit the page devoted to ACOs at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website at https://PharmPractice7e.ParadigmEducation.com/FeeForService.

Safety-Oriented Technology and Utilization

Properly selecting, implementing, utilizing, and maintaining pharmacy technology and automation are key to the safe filling, dispensing, compounding, and administering of medications (such as the use of bar code scanning for drug verification). Pharmacists can encourage the prescribers they work with to use e-prescribing software and employ common terminology in their prescription and medication orders, avoiding any abbreviations that have proven confusing and unsafe (as determined by the ISMP). Technicians contribute to this effort by getting to know the ins and outs of each element of pharmacy software and automation equipment and following procedures without skipping steps.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

Instead of asking “Do you have any drug allergies or health conditions?” it can be more effective to ask: “Can you think of any changes you have had in your drug allergies or health conditions? Have you started taking any new medications, dietary supplements, or herbal products since you have last seen us or that you may not have mentioned before?”

Addressing Psychosocial Causes of Human Errors

The level of errors where technicians and pharmacists have a great deal of influence is that of individual human errors. One may ask, if all personnel have been taught the correct procedures, why are they not always done? The answer lies in seven social and psychological reasons, including incomplete information error, incorrect assumption error, selection error, capture error, rushed error, distraction error, and fear error. These are helpful to be aware of to work against them in practice.

An incomplete information error occurs when a full medication profile is not available because the patient was not asked sufficient or proper questions about their medications, supplements, and allergies; the answers were somehow not recorded in the profile; or the patient withheld information deliberately or by accident of memory. For instance, consider a patient who is allergic to penicillin receiving a penicillin-related antibiotic. It is crucial to strive for complete medication profiles in order to avoid these errors.

An incorrect assumption error occurs when an essential piece of information is assumed to be true without verification; therefore, a wrong decision is made. An example of an assumption error is misreading a poorly written abbreviation, drug name, or direction on a prescription. Double-checking missing or questionable information is the only cure.

Technicians and pharmacists must be careful to double-check the desired NDC number on the prescription and on the stock medication and not go by memory of the package or usual dosage strength.

A selection error occurs when two or more options seem to exist (or do exist), and the wrong option is chosen. The most common error in dispensing and administration is drug misidentification. An example of a selection error is mistakenly grabbing off the shelf a look-alike or sound-alike drug instead of the prescribed drug or choosing an immediate-release formulation instead of an extended-release drug. Similar manufacturer labels can also lead to a mistaken medication selection. Double-checking information and using the NDC bar code scanner can help eliminate these problems.

A capture error is an error of inattentiveness and habit. It occurs when a more practiced behavior automatically takes the place of a less familiar one because of a failure to notice or capture the differences in the situation. For example, the usual prescription for alprazolam is 1 mg, but an elderly woman of low weight receives a prescription for 0.25 mg. Rather than attending to this difference, you simply fill it as if it were the norm, thus preparing the medication at four times the prescribed dose! (You assume it is up to the pharmacist or tech-check-tech supervisor to notice and correct the error.) The opposite can happen also. Suddenly a prescription comes in for a far higher dose than the usual range, which can be a danger signal that a prescriber has made a mistake. Instead of querying the pharmacist and prescriber, you just follow habit and fill the prescription. A mistake was made, but the pharmacist also approves the prescription without question, and the patient gets a medication that can cause harm.

In both cases, the remedy for a capture error is to remind yourself with each and every prescription to focus on the details. Taking a new breath with each prescription can be a way to remind yourself to also refresh your mind with each new prescription.

A rushed error is an error that is becoming increasingly common—an error made because of the pressure to meet corporate or self-imposed time constraints, resulting in cut corners and unnoticed danger alerts. The interior monologue is, “If I take the time to check this, I will be late and not meet the production quotas or customer satisfaction surveys,” or “More waiting will make this patient even angrier.” Elements that would have been carefully checked with more time are left unchecked, and errors go unnoticed. To address this, slow down rather than speed up when feeling this inner pressure, take a breath to clear your head, and remind yourself that patient safety always overrides speed, and you are not productive if you are harming the patient, which in the end also harms the pharmacy, your job, and your career.

Practice Tip

Practice TipAt the end of any step, take five seconds to look over what you have done to ensure that no mistakes have been made, like proofing a paper.

A distraction error occurs when a technician or pharmacist is interrupted in the middle of a filling process and forgets a portion of key information or train of thought. An example is being interrupted in a metric measurement calculation by a patient query, a customer call, or a text on a cell phone. When you return to the calculation, the wrong decimal place that was going to be corrected is missed; or you dispense the wrong number of tablets (e.g., because the correct number was not double-checked at the conclusion of the phone call) or inadvertently override an alert due to the distraction.

Practice Tip

Practice TipNot only can a cell phone create distractions, but it can also create opportunities for inadvertently compromising patients’ privacy.

Determining when and where in the prescription-filling process it is safe to answer a customer call or query or be diverted for another work task is essential. For instance, when you are completing a medication-related task, what are the points in the process when stopping and answering the pharmacy telephone is not appropriate? When is it appropriate and necessary? The pharmacist and training personnel can help determine this. Knowing when to allow interruptions and when not to do so is vitally important in developing individual safety practices—and having the confidence to adhere to such practices during the pressure of a workday is key. You must also put your cell phone away from your body (along with other personal belongings or devices) and not check it except at breaks.

A fear error occurs when a technician fears the consequences of speaking up and asking a technician colleague, a pharmacist, or a prescriber to assist or double-check a prescription element. As a technician, you usually are the one to enter a prescription, talk at length to the patient about their medication and allergy profile, submit the prescription for medication reconciliation and insurance claims, and fill it. As such, you “own” a substantial portion of the prescription-filling process and can many times spot errors. However, the fear of bothering, embarrassing, or angering someone can mistakenly become more important than patient safety.

Safety Alert

Safety AlertEach person who participates in the filling process has the opportunity to catch and correct a medication error. Maintaining focused attention when filling prescriptions is important to avoid errors.

A lack of confidence in one’s own knowledge may also make someone reluctant to speak up and say, “Can we check this?” The only way around these fears is to face them and know that if you choose this career, you must choose daily to be brave enough to speak the truth when you see it and to question those things that need questioning. Remind yourself that these courageous choices matter very much to the patients as you have their lives and health in your hands with each prescription.

For a sense of how some of these errors work in everyday life, consider the case of Emily Jerry (described in Chapter 2), the two-year-old who died because of a medication error. Numerous psychosocial factors were involved. The uncertified technician was distracted on her cell phone making plans for her upcoming wedding. Though she did have the courage to admit that she might have made a mistake, the pharmacist (who lost his license) did not take the time to recalculate. The pharmacy was understaffed, and the pharmacist felt rushed. He was found guilty of involuntary manslaughter and sentenced to five years in prison and a maximum fine of $10,000. This case resulted in the passage of Emily’s Law in Ohio, which establishes standards for qualified pharmacy technicians.

Cell phone calls, texting, and internet activity can lead to distractions, causing medication errors.

IN THE REAL WORLD

IN THE REAL WORLD

While entering new prescriptions, a technician named Thuy noticed an unusually high dose and nonstandard dosing regimen for the antipsychotic quetiapine (Seroquel)—300 mg in the morning, 450 mg in the evening. Thuy pointed out to the pharmacist that the dose seemed high and that it was odd that the morning and the evening doses were not the same. The pharmacist looked into it—this patient had not had Seroquel before, so this dose was too high to be an appropriate starting dose, and it was odd to start a patient with different morning and evening doses. The pharmacist called the patient’s nursing home and learned that the wrong patient’s name had been written on the order! So the technician’s simple question spared the patient from receiving a high dose of a powerful antipsychotic medication that wasn’t intended for them.

Step-by-Step Task Analysis of Prescription Filling

Human errors with medications occur most frequently at two crucial points in the process: prescription filling and administration. Knowing this can aid in the identification and prevention of future problems. Technicians and pharmacists use root-cause analysis to examine their own work flow to determine potential for errors and prevention steps to avoid them.

Prescription-Filling Errors

In most pharmacy programs, technicians are taught to check each prescription against the original prescription and medication information sheet at least four times:

during the computer order entry and printing of the label

when the medication is taken from the shelf

when the NDC number/bar code scan is verified

during the counting of the dosage to fill the prescription

Safety Alert

Safety Alert

Incorrect drug identification is the most common error in dispensing or administration.

Pharmacists check the medication profile and prescription entry at the beginning of the dispensing process; then they check the medication, label, and patient education material at the end. They also answer questions or verify elements during the filling process if needed for calculations or by technician request. Technicians and pharmacists are fully responsible for these specific technical errors in the filling process:

A wrong drug error, occurs when the incorrect drug is substituted for the one prescribed; when the wrong drug has been prescribed by accident for the medical indication, and the prescriber is not alerted to adjust the prescription; when the wrong ingredients are mixed during drug compounding; or when the wrong medication label is applied and given to the wrong patient.

An adverse drug error, occurs when the prescribed drug initiates an allergy or an adverse drug interaction because a flag is missed or the medication profile was incomplete.

A wrong amount error (or wrong dosage error), occurs when a dose is either above or below the correct amount by more than 5%; or when the wrong supply of medication is provided.

A mislabeling error, occurs when a medication has incorrect information on it leading to incorrect usage; or when the wrong patient receives the medication

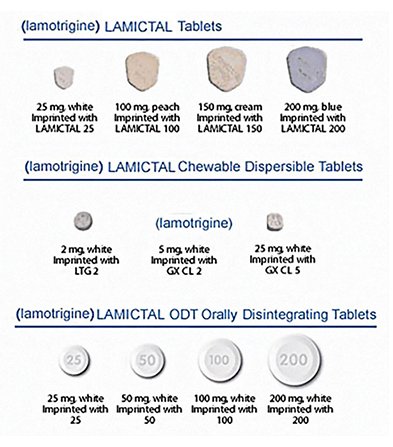

A wrong formulation error, occurs when the dose formulation provided does not fit the physician’s order. Examples include a drug given by mouth for a drug ordered as an intramuscular (IM) injection; a transdermal patch instead of a tablet; a drug prescribed for IM instead of subcutaneous administration; or an immediate-release drug dispensed instead of a controlled- or extended-release drug. How does this happen? Consider that the brand name drug Lamictal is available as an immediate-release, extended-release, chewable dispersible, and oral disintegrating tablet!

A documentation error, occurs when essential information is missing or not properly noted, such as a prescription, an allergy, a patient request, or other information in the medication profile; or when insurance or billing claims are not properly processed.

A medication education error, occurs when the proper medication education materials and counsel are not passed on to the patient or medication administrator.

A contaminated product error, occurs when aseptic technique is not followed properly in compounding and the drug is no longer sterile, causing a microorganism infection.

Lamictal 25 mg comes in many dosage formulations, including Lamictal XR (not shown), which can cause errors by inattentive pharmacy staff or unaware prescribers.

Patient or Caregiver Drug Administration Errors

Many errors occur beyond the pharmacy walls at the point of administration. In the community pharmacy, the medications pass through the hands of the patient or guardian, so the technician and pharmacist must provide adequate education in the forms of medication label, information sheets, and pharmacist counseling about proper administration. In the hospital setting, the administering hands are those of the nurse (utilizing bar code technology at the bedside), so nurses, too, must be educated by the pharmacy staff. Without this education, the following errors are common:

A wrong time error occurs when a drug is given 30 minutes or more before or after it was ordered to be administered, up to the time of the next dose. This is a common error in short-staffed hospitals and nursing homes and in patient homes.

An extra dose error occurs when a patient receives more doses than were prescribed.

An omission error occurs when a prescribed dose is due but not administered.