14.3 Step-by-Step Overview of Filling and Administration Education

The only way to stop medication errors is to review the steps in the filling process and key points where errors can be prevented. Figure 14.2 provides an overview of a typical step-by-step prescription-filling process for community and hospital pharmacy practice settings, medication. As the steps are briefly described, it is helpful to think of each as entailing three factors:

information that needs to be obtained or checked

resources that can be used to verify information

potential medication errors that would result from a failure to obtain or check the information using the appropriate resources

Safety Alert

Safety Alert

If information is missing from a prescription or medication order, a pharmacy technician must obtain that information from the prescriber. The technician should never make conjectures regarding the missing content.

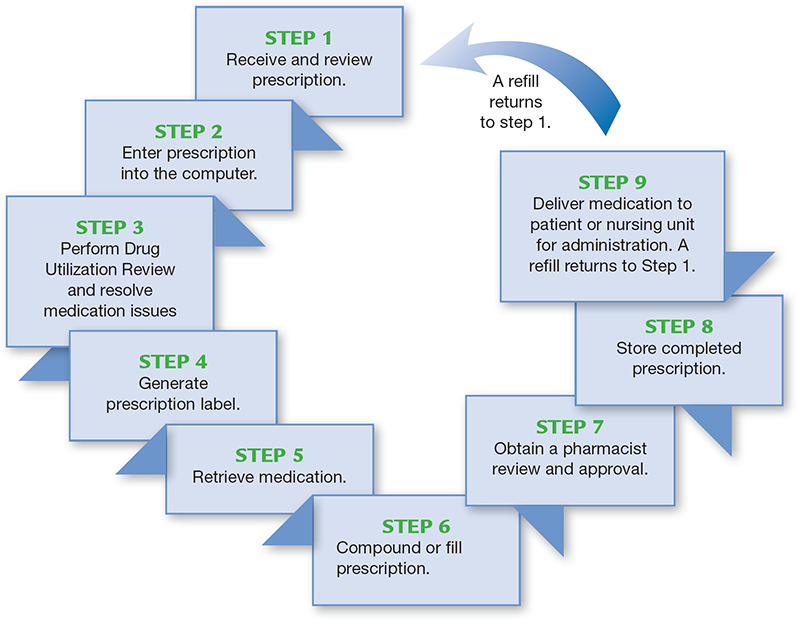

Figure 14.2 Prescription-Filling Process

Each step in the prescription-filling process is an opportunity to do things correctly or make an error. At each step, there is also a chance to catch and correct any previous errors and to make a positive difference in someone’s life.

Step 1: Receive and Review Prescription

In receiving a prescription or medical order, an initial check of all key pieces of information is vital. Table 14.2 lists the data needed and the resources to avoid potential errors. A thorough review by the pharmacy technician and the pharmacist substantially reduces the chances that an unidentified error will continue throughout the filling process. Verify the legitimacy of the prescription or medical order first and then the individual components of the prescriber, patient, and prescription information. Any unclear information must be clarified.

Safety Alert

Safety Alert

A prescriber’s signature is required for an electronic or written prescription to be valid.

In at least 1.7% of all prescriptions dispensed in a retail pharmacy, some type of medication error occurs. Medication errors are generally not reported.

Table 14.2 Step 1: Receive and Review Prescription

Information to Check |

Resources to Verify Information |

Potential Errors Resulting from Failure to Check/Verify Information |

|---|---|---|

Legibility: Are there any typos or seeming errors in the e-Rx that are confusing? In a handwritten Rx, can the prescription be read clearly? |

Physician, patient, independent reviewer, such as a pharmacist or a nurse |

Prescription misread |

Prescriber information: Is the prescription valid? Did the prescriber sign the prescription? |

Physician, pharmacist, nurse |

Out-of-date (i.e., invalid) prescription filled; fraudulent prescription filled; patient receives medication intended for another patient |

For controlled substances, is the prescriber’s Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) number listed? |

||

Are the prescriber’s name, address, and phone number printed on the prescription? |

||

Patient information: Is all necessary information included? |

Physician, patient, immediate family member, patient profile, pharmacist, nurse |

Incorrect patient selected; contraindicated drug dispensed |

Is this prescription for this patient? |

||

Are the patient’s name, date of birth, address, phone number, and allergies provided? |

||

Does the information match the profile? |

||

Medication information: Is all necessary information included? |

Patient, physician, family member, patient profile |

Wrong medication dispensed; wrong form or formulation dispensed; wrong dose dispensed; patient administers incorrectly; out-of-date (i.e., invalid) prescription filled |

Are drug name, dose, dosage form, route of administration, refills, directions for use, and dosing schedule included? |

||

Is the prescription dated? |

Verbal Order Precautions

A common cause of error in prescriptions over the phone or in person is sound-alike drugs; if the caller or prescriber did not spell out the name of the drug and the pharmacist (or the technician, in some states) is unclear about the correct name, the order should be spelled or clarified. If the nurse calls it in, the caller is encouraged to read back the order to minimize errors. Any verbal prescription order should include all of the information necessary to verify the credibility and legality of the prescriber, including the National Provider Identifier (NPI), DEA, or license number, depending on what is needed.

In a community pharmacy, handwritten prescriptions still come in that are incomplete. If you are unable to seek out the complete information, do not fill the prescription.

There are many occasions when a nurse will leave a voicemail for a new prescription. In some states, the technician is allowed to transcribe the prescription. In one case, a technician misheard “Pamelor” (an antidepressant) for “Tambocor” (an anti-arrhythmic); the error was not discovered for one month. Fortunately, the patient experienced no adverse outcomes. This error might have been prevented by reviewing the profile and calling the nurse back for clarification.

Safety Alert

Safety Alert

C-III, -IV, and -V prescriptions should not be filled after six months; non-controlled medications should not be filled after one year from date of prescribing.

Abbreviation and Signa Code Errors

Prescribing errors include the use of nonstandard abbreviations, confusing look-alike and sound-alike drug names, poor handwriting, and “as directed” instructions. An “as directed” instruction does not allow a pharmacist to verify normal recommended dose scheduling or to reinforce the correct dosing regimen to patients. Though errors on sound-alike drugs are less common with e-Rxs, the “sig” could be inappropriate due to incorrect selection in the drop-down menu, or the refill field may be missing.

IN THE REAL WORLD

IN THE REAL WORLD

The very potent drug methotrexate is most often prescribed for arthritis in a specified oral dose of “q wk” or once weekly. An unsuspecting technician entered the dose as 28 mg once daily rather than once weekly. This damaging error was not caught by the pharmacist, and the patient continued taking the incorrect dose at seven times the prescribed dose, which was toxic to the bone marrow, until the damage was finally noticed by the prescriber!

In contrast, while entering an order for pregabalin (Lyrica), a drug used to treat neuropathic pain, an attentive technician named Nelya noticed that the directions on the order were not standard—1 to 2 tablets at bedtime “prn” (as needed). She called the pharmacist over to alert him: “I’ve never seen an ‘as-needed’ order for pregabalin before.” The pharmacist agreed—and in the drug’s labeling there is no such dosing. The pharmacist called the doctor’s office, and the prescriber modified the directions. The patient was spared the additional dosing, which would not have been more effective at treating her pain and might have caused additional side effects.

The Joint Commission has assembled a list of problematic abbreviations to avoid (see Table 14.3), and if any of them occur on the prescription, make sure that they are verified and replaced with the appropriate substitution so that no errors result. Many of these potential “abbreviation errors” have been discussed previously, but they are listed here for reinforcement.

Table 14.3 The Joint Commission’s Official “Do Not Use” Abbreviation List1

Do Not Use |

Potential Problem |

Use Instead |

|---|---|---|

U, u (unit) |

Mistaken for “0” (zero), the number “4” (four), or “cc” |

Write “unit” |

IU international unit |

Mistaken for “IV” (intravenous) or the number “10” (ten) |

Write “international unit” |

Q.D., QD, q.d., qd (daily) |

Mistaken for each other |

Write “daily” |

Trailing zero (X.0 mg)* |

Decimal point missed |

Write X mg |

Lack of leading zero (.X mg) |

Decimal point missed |

Write 0.X mg |

MS MSO4 and MgSO4 |

Can mean morphine sulfate or magnesium sulfate Confused for one another |

Write “morphine sulfate” Write “magnesium sulfate” |

1 Applies to all orders and all medication-related documentation that is handwritten (including free-text computer entry) or on preprinted forms.

*Exception: A “trailing zero” may be used only where required to demonstrate the level of precision of the value being reported, such as for laboratory results, imaging studies that report size of lesions, or catheter/tube sizes. It may not be used in medication orders or other medication-related documentation.

Step 2: Enter Prescription into the Computer

In the community pharmacy setting, the pharmacy technician often enters the prescriptions into the computer database, whereas in the hospital it is the pharmacist or the prescriber who usually enters the medication order. As each piece of information is entered, the prescription should be compared with choices from the computer menu. Check the brand and generic drug options and their spellings to determine whether the information on the prescription and in the computer match. Special attention should be paid to dosages, formulations, concentrations, and the increments of measure. Prescriptions that contain unapproved, error-causing abbreviations must be reviewed carefully with a pharmacist or confirmed with the prescriber.

Once entered, each data element should be checked again before the entry process is finalized. In many pharmacies, the original prescription is scanned so that the pharmacist can check the technician’s entry on the screen during the verification process. Table 14.4 lists the information needed and the resources used to avoid potential errors in the second step of the prescription-filling process.

Table 14.4 Step 2: Enter Prescription into the Computer

Information to Check |

Resources to Verify Information |

Potential Errors Resulting from Failure to Check/Verify Information |

|---|---|---|

Are data choices from the computer menu and those on the prescription the same? |

Cross-check brand/generic names for identical spelling. |

Look-alike or sound-alike drug selection error made |

Does the spelling on the prescription match the drug selection options? |

||

Do the increments of measure on the drug selection options match those on the prescription (e.g., gram versus milligram versus microgram)? |

Cross-check measure prescribed with drug choices listed. |

Patient given incorrect dose |

For the dose selected, do available strengths or concentrations match? |

Cross-check dose written with available strengths or concentrations on selection menu; cross-check dose or concentrations that use decimals or leading or trailing zeros. |

Patient given incorrect dose |

Does the dose or concentration have leading or trailing zeros? |

||

Does it require a decimal? |

||

Do available forms match the route selected? |

Match route to formulation choices (e.g., injection route corresponds to intravenous [IV] or intramuscular [IM] drug; oral route corresponds to capsule, tablet, liquid, or lozenge). |

Inappropriate form or formulation selected |

Brand Versus Generic

A common pharmacy dilemma is when a prescribed brand-name cough and cold remedy is not carried by the pharmacy, is no longer available, or is not covered by insurance. Most software will list a generic equivalent. However, if the recommended generic equivalent is not in stock, caution should be used before offering another generic equivalent. Other options would contain different ingredients, which could change their bioequivalency. The technician or the pharmacist then needs to contact the prescriber to discuss a therapeutically equivalent product with similar but not identical ingredients.

Safety Alert

Safety Alert

Be sure to look for DAW status on prescriptions but especially for thyroid medications. If a new prescription is received, check the patient’s profile for past history to see what generic or brand name was dispensed, and then verify if correct.

Another common problem arises when a brand name drug, such as Synthroid, is prescribed as a “dispense as written” (DAW, or do not substitute). If the technician does not enter the correct DAW code, the computer may default to the less expensive generic drug levothyroxine, and the wrong drug will be dispensed if not detected in the pharmacist check.

Dosage Form and Formulation Mix-Up Dangers

Does the dosage form or formulation match the route of administration? Be aware that certain concentrations or formulations of a medication are often associated with a particular administration route. For example, methylprednisolone acetate (Depo-Medrol) and methylprednisolone (Solu-Medrol) are both injectable and have similar dosages, depending on the clinical situation. However, Depo-Medrol is for IM administration only and is a cloudy suspension when reconstituted. Solu-Medrol is for IV administration and is a clear solution. A serious and potentially fatal medication error could occur if a suspension were inadvertently administered by the IV route, as the suspension could cause damage to veins.

Another mix-up may occur with morphine sulfate. Morphine sulfate is available in a concentrated liquid formulation (20 mg/mL) and a less concentrated liquid (4 mg/mL and 2 mg/mL). Entering or selecting the wrong concentration would result in a fivefold to tenfold error and cause serious respiratory depression in the patient. Other examples include ointments versus creams in topical products or solutions versus suspensions in ophthalmic and otic medications. In some cases, substituting a capsule for a tablet or vice versa is permissible. If you’re unsure, always check with the pharmacist.

Related Drugs with Different Dosages and Sigs

If a related drug is entered instead of the correct one, the mistake can be more easily missed by both technician and pharmacist. Certain Schedule II pain medications are a particular source of potential error. For instance, OxyContin is the extended-release formulation, and oxycodone IR is the immediate-release formulation. Because of their different functions and metabolizing rates, these drugs should be prescribed differently. OxyContin is commonly dosed every 8 to 12 hours, whereas oxycodone is dosed every 4 to 6 hours. To make things worse, the two drugs are often prescribed together. Entering the right drug(s) into the computer profile with the right dosage directions is extremely important!

Teaspoons Versus Milliliters

Mix-ups occasionally occur with the teaspoonful and milliliter dosage amounts. A prescriber may either inadvertently write the wrong instructions, or the technician might enter an incorrect measurement form for the dosage into the computer. For example, a prescription may be written for 3.5 mL of an antibiotic, but the order is entered as 3.5 teaspoonfuls (or 17.5 mL). If the pharmacist misses the error, the pediatric patient would receive five times the recommended dose. Therefore, it is recommended to always use milliliters for computer entry and labeling to minimize errors.

For each prescription, the technician has to stay attentive and focused while entering patient medication profile and prescription information into the computer and checking the DUR and insurance prompts, working against screen and alert fatigue.

Step 3: Perform Drug Utilization Review and Resolve Medication Issues

While working through DUR and insurance processes, multiple prompts and alerts will pop up on the screen about repetitive drug therapies, dosing ranges, existing allergies, contraindications in pregnancy or in women of childbearing potential, and problematic interactions with other medications (see Table 14.5). Beware of alert fatigue. This is when the technician and/or the pharmacist start to have a relaxed attitude toward the screen alerts. One has to find ways to stay alert, engaged, and focused with each new prescription and screen prompt.

Table 14.5 Step 3: Drug Utilization Reviews and Resolving Medication Issues

Information to Check |

Resources to Verify Information |

Potential Errors Resulting from Failure to Check/Verify Information |

|---|---|---|

Drug screening: Does the prescribed medication interact with other conditions or medications listed on the profile? |

Patient, physician, family member, patient profile, interaction screening program, electronic messages from insurance provider, drug information resources (e.g., books, call centers, package inserts, patient information handouts) |

Contraindicated drug dispensed; drug–drug or drug–disease interaction occurs |

Pediatric dosing: Are the prescribed dose and frequency of dosing in a pediatric patient consistent with manufacturer recommendations and pharmacy references? |

Original prescription, physician, package inserts, electronic database, reference texts, pharmacist experience |

Serious overdose (or underdose) leading to side effects, adverse reactions, or treatment failure |

Geriatric dosing: Are the prescribed dose and frequency of dosing in a geriatric patient consistent with manufacturer recommendations and pharmacy references? |

Original prescription, physician, package inserts, electronic database, reference texts, pharmacist experience |

Serious overdose leading to side effects or adverse reactions |

Pregnant (or potentially pregnant) and nursing women dosing: Is the prescribed drug indicated in pregnant women or women of childbearing potential? Does the drug pass into the breast milk? |

Physician, package inserts, electronic database, reference texts, questions to patient, pharmacist experience |

Congenital birth defects, side effects in breast-feeding infants |

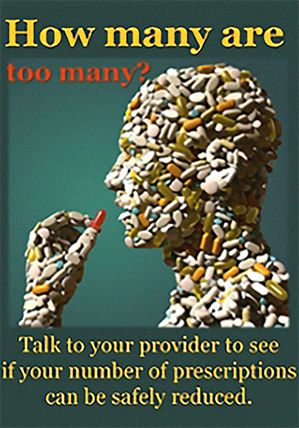

The risk of medication errors and harmful drug interactions obviously increases with the number of medications, pharmacies, and prescribers that an individual patient uses, especially among elderly patients. For example, if a patient is on many drugs from many prescribers and specialists and suddenly is prescribed clarithromycin (Biaxin) to fight an infection, it may interfere with and increase the risk of toxicity of other drugs, such as blood thinners, antiseizure medications, or cholesterol-fighting drugs. Certain high-risk drugs such as warfarin and the arthritis drug methotrexate can interact with many drugs and always require careful review by the technician and the pharmacist. Even at normal therapeutic doses, the interactions of drug accumulations can lead to serious adverse reactions or even death.

IN THE REAL WORLD

IN THE REAL WORLD

While inputting a refill request, Marina discovered a problem in the pattern of a previously entered order for the tapering drug therapy (decreased gradually before stopping) of the corticosteroid prednisone. Prednisone may be tapered so that patients do not experience withdrawal symptoms such as severe fatigue, weakness, body aches, and joint pain. The taper sequence had been entered this way:

50 mg daily × 7 days, 40 mg daily × 7 days, 30 mg daily × 7 days,

10 mg daily × 7 days, 5 mg daily x 7 days, 1 mg daily × 7 days, then stop.

Marina tacked a sticky note to the prescription label printout: “Looks like the 20 mg dose was missed” and handed it to the pharmacist. The pharmacist checked the original prescription, found that the taper sequence had indeed been entered incorrectly, and fixed it.

Allergy-Related Alerts

The computer software generally flags allergies, but it is often the pharmacy technician who sorts through the questions and brings the problematic ones to the attention of the pharmacist for professional judgment. For example, if the patient is allergic to codeine, can they tolerate hydrocodone, a similar narcotic? Similarly, if a child is allergic to penicillin, there is a chance of cross-sensitivity with other antibiotics.

Problems arise if the patient or the caregiver has not told the technician, pharmacist, or prescriber about any allergies, so technicians need to remember to ask the patient, probing for any allergies that may have been missed. Also, how is the allergy manifested? Is the patient’s allergy a gastrointestinal upset, rash, shortness of breath, or another symptom? This information is key for the pharmacist to make a correct decision.

The more drugs and supplements one takes, the more likely the errors and adverse drug reactions. A 2013 Mayo Clinic study found that more than 50% of US citizens are taking at least two prescriptions while 20% are on five or more, and these numbers are rising. Many patients are also taking diet supplements, including herbal drugs, which also interact with prescription drugs. So all the more caution is needed in attending to DURs.

Interactions and Duplication Alerts

The computer software also flags duplicate therapy that may lead to serious adverse reactions. For example, a patient may be taking both ibuprofen and etodolac, which are similar anti-inflammatory and pain medications that, if taken together for a long period, can lead to a gastric bleed or ulcer. Another example may be a patient prescribed one cholesterol drug from a heart specialist and another one by the primary care physician.

Safety Alert

Safety Alert

The patient profile must always be checked for existing allergies or possible drug interactions prior to dispensing medications.

Identifying these duplications saves money and reduces the risk of serious side effects or adverse reactions. The pharmacist must decide whether to counsel the patient or contact the prescribing physician before approving the filling of this prescription.

Special Considerations for Vulnerable Populations

As noted many times, special considerations must be paid to the prescription dosages for pediatric patients, especially those younger than age two. The prescriber must make the dosages appropriate for neonates (newborns), especially those born prematurely, and these must be triple-checked during input.

Also, if a woman is pregnant (or of childbearing potential), a more careful review of her prescriptions must always be done by the technician and the pharmacist to avoid any potential harm to a developing fetus. Finally, patients of low weight or older adult patients may require a lower dose of medication. Seniors often have age-related declines in liver and kidney functions and other body changes. In many cases, a drug may be contraindicated, or the dosage may need to be decreased from the average adult rate by 25% to 50% or more.

Physiological Causes of Medication Errors Every person is genetically unique, and the speed at which a body can process a medication varies tremendously from person to person. For instance, a patient may lack an enzyme that helps remove or eliminate medications from the body, thus leading to serious harm from what would normally be a safe medication at the prescribed dosage. A patient’s reduced kidney function can also cause medication difficulties since the kidneys play an important role in excretion—the process by which drugs are removed from the bloodstream. Many patient populations have decreased kidney function because of age or disease.

Elderly patients, newborns, and premature babies have diminished kidney function, as well as patients with chronic renal failure, high blood pressure, diabetes, or alcohol abuse. If a medication dose is not lowered in consideration of these conditions, the drug can accumulate to toxic levels, causing an adverse reaction. Consequently, kidney function is one of many factors for the pharmacist to consider before approving and verifying a prescription. In the hospital, the pharmacist has access to pertinent laboratory results, such as kidney function. In the near future, community pharmacists may have access to the patient’s lab results.

Patients are not always aware of the need to report their conditions, or they forget them. You can assist the pharmacist by being assertive and persuasive in drawing information out of patients for creating and updating medical condition notes and medication profiles in the computer database.

Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs

There are certain medications where small differences in dose or blood concentration may lead to adverse reactions or therapeutic failures. These medications are said to be narrow therapeutic index drugs. For these drugs, there is a small difference between a therapeutic dose and a toxic dose.

Certain antibiotics (such as aminoglycosides), antiseizure agents (such as carbamazepine, phenytoin, and phenobarbital), and cardiac medications (such as digoxin, digitoxin, flecainide, and warfarin) are considered to have a narrow therapeutic index. It is common practice to carefully monitor patients who are taking a narrow therapeutic index drug. This often means laboratory testing of drug levels in the blood. Doses can be adjusted based on drug levels; if the drug level is too low, the dose may be increased. If the drug level is too high, the dose may be decreased.

Medication error rates are higher with narrow therapeutic index drugs. Furthermore, negative consequences of errors are amplified with these drugs. For example, if the blood levels of the injectable antibiotic gentamcin are too high, it can cause kidney damage and irreversible hearing loss. If too little of the blood thinner warfarin is used, a patient could suffer from a stroke or pulmonary embolism. As a technician, it is your job to familiarize yourself with narrow therapeutic index drugs so that you can keep your patients safe.

Step 4: Generate Prescription Label

After generating the label, cross-check it with the original prescription to make sure that a typing error or inherent program malfunction did not alter the information and that it is for the proper patient. Table 14.6 offers an overview to avoid potential errors in the fourth step.

Table 14.6 Step 4: Generate Prescription Label

Information to Check |

Resources to Verify Information |

Potential Errors Resulting from Failure to Check/Verify Information |

|---|---|---|

Has the patient information been cross-checked? |

Compare label generated with original prescription. |

Wrong patient, medication, or dose selected |

Are the label and original prescription identical? |

Compare label generated with original prescription. |

Wrong patient, medication, or dose selected |

Are the leading or trailing zeros and unapproved abbreviations correct? |

Check with pharmacist or prescriber. |

Incorrect dose selected |

Do all the data elements match those of the original prescription (e.g., prescriber information, patient information, medication information)? |

Use additional information generated on label reference for verification (e.g., brand/generic names; NDC number; manufacturer’s name; patient’s address, phone number[s], date of birth). |

Inappropriate form or formulation selected |

Step 5: Retrieve Medication

The most common error is a selection error. Look-alike labels, brand or generic names, and medication shapes or colors can all contribute to medication errors. For instance, in one infamous case, Troppi v. Scarf, a pharmacist accidentally dispensed Nardil, an antidepressant, instead of Norinyl, a contraceptive. The woman who received the incorrect drug gave birth to a child, and the Michigan Court of Appeals held the pharmacist liable not only for the medical expenses incurred in the woman’s pregnancy, but also for the costs of raising the child.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

Trazodone and tramadol are similar-sounding generic drugs with two distinct indications. Trazodone is an antidepressant while tramadol is an analgesic. Selecting one of these medications without checking the NDC number could have serious consequences.

Sometimes manufacturers deliberately use look-alike and sound-alike labeling to attract customers. The manufacturer of Maalox was attempting to increase its market share by a product line extension—using a brand name to sell various combinations of active ingredients with different indications—leading to consumer selection errors. At the request of the FDA, the manufacturer voluntarily recalled its confusing products, changed the product names, provided educational programs for healthcare professionals and consumers, and added safety monitoring and a reporting program for its products.

National Drug Code Matchups and Bar Code Scanning

To avoid an incorrect selection from the storage shelf, match the NDC numbers, drug names, and other information available on manufacturers’ labels or patient information handouts, scanning the bar codes to lead you to the right choice. The reason that NDC numbers serve as such an effective cross-check is because each numeral in the NDC number combination is specific to a particular drug and a specific strength, dosage form, and packaging for it. For example, bupropion 150 mg SR will have a different NDC than bupropion 150 mg XL. The SR formulation is commonly dosed twice daily while the XL formulation is dosed once daily. Table 14.7 offers a safety overview of Step 5.

Safety Alert

Safety Alert

Generics of both Fioricet and Fiorinal are dispensed as white tablets. An NDC bar code scan ensures that the correct medication is dispensed. If generic Fiorinal is dispensed in error to a patient with an aspirin allergy, a serious reaction can occur.

Table 14.7 Step 5: Retrieve Medication

Information to Check |

Resources to Verify Information |

Potential Errors Resulting from Failure to Check/Verify Information |

|---|---|---|

Has the available information on the manufacturer’s label been used to verify the medication selection? |

Original prescription, shelf- or bin-labeling systems, manufacturers’ names, NDC numbers, brand names and generic names, pictographic medication verification references or computer programs |

Medication selection error made |

Does the brand or generic name on the label match the product container? |

||

Do the dose strength and form on the label match those indicated on the product container? |

Original prescription, shelf- or bin-labeling systems, manufacturers’ names, NDC numbers, brand names and generic names, pictographic medication verification references or computer programs |

Incorrect dose, form, or formulation selected |

Do the NDC numbers and manufacturers’ names match those listed on the label? |

Bin-labeling systems, NDC numbers, pictographic medication verification references or computer programs |

Incorrect dose, form, or formulation selected |

Shelving Order and Medication Image Double-Checks

To prevent similarly labeled drugs or doses from being mixed up, drugs will often be shelved in a nonalphabetic or illogical order, so that the technician or pharmacist is less likely to select the wrong stock bottle with a similar name next to the right one. Some pharmacies use a shelf-labeling system to organize inventory and possess a computer-based tablet identification program. You can visually verify the medication selected by the NDC number and name with the picture called up by the bar code scan.

Medications with near-identical names and similar manufacturer packaging can lead to the wrong selection; always check the NDC number or scan the bar code.

Step 6: Compound or Fill Prescription

Calculation and substitution errors are frequent sources of pharmacy-related medication errors in all practice settings as explained in Chapter 6. Do not allow interruptions, distractions, or multitasking during calculations. You should write out your calculations and have a second person check the answers. If you must stop before the calculations process is complete, be sure to start over from the beginning when you return. Table 14.8 presents safety tips for the sixth step.

Safety Alert

Safety Alert

Take steps to minimize interruptions during the prescription-filling process. When necessary (such as when completing calculations), do not allow interruptions at all.

Technology presents its own unique potentials for safety checks and for errors. All equipment must be maintained, cleaned, and calibrated on a regular basis. In most circumstances, technology failures are the result of user error, but inherent technology malfunctions and program glitches do occur, so safety monitoring must be standard. Good practices include consistent, timed checks of the technology’s accuracy (e.g., computers, scales, robots, infusion pumps, automated dispensers, and compounders).

Proper safety checks are not limited to sophisticated equipment. The act of cleaning the counting trays and spatulas on a regular basis is an important part of medication safety. Consider the potential for serious harm to a patient if the residue or dust from an allergy-causing medication from one patient contaminated another patient’s prescription. For example, penicillin- or sulfa-containing medications should preferably be counted on dedicated counting trays because of the high prevalence of penicillin and sulfa allergies. The counting tray must be cleaned with isopropyl alcohol after any of these drugs are dispensed. If you are dispensing oral hazardous substances, such as methotrexate, then the counting tray must also be carefully cleaned to prevent contamination.

Table 14.8 Step 6: Compound or Fill Prescription

Information to Check |

Resources to Verify Information |

Potential Errors Resulting from Failure to Check/Verify Information |

|---|---|---|

Have the amount to be dispensed and the increment of measure (e.g., gram, milligram, microgram) been reviewed? |

Amount dispensed (count twice), original prescription |

Incorrect quantity or incorrect dose dispensed |

Does the prescription require a calculation or measurement conversion? |

Write out the calculation and conversions; ask another person to review the calculation. |

Incorrect dose dispensed |

If you are using equipment, has it been calibrated recently? |

Equipment (check calibration), pharmacist, patient information handout, package insert |

Incorrect dose dispensed |

Does the medication dispensed require warning or caution labels? |

Pharmacist, patient information handout, package insert |

Administration error made by patient |

Step 7: Obtain a Pharmacist Review and Approval

Though the pharmacist is legally responsible for every prescription or medication order filled, it is not practical for pharmacists to verify each step. Instead, the pharmacist verifies the initial computer entry and the original prescription/medication order, and the quality and integrity of the end product. You are responsible for laying out all the information in a logical order for the pharmacist to check, including the medication’s stock bottle, calculations, labeled medication container, and original prescription. The same verification process is needed for a compounded sterile or nonsterile preparation. Table 14.9 offers safety counsel for the seventh step.

Table 14.9 Step 7: Obtain a Pharmacist Review and Approval

Information to Check |

Resources to Verify Information |

Potential Errors Resulting from Failure to Check/Verify Information |

|---|---|---|

Did the pharmacist review the prepared medication? |

Original prescription, stock medication bottle or vial, calculations |

Invalid or out-of-date prescription filled |

Can the pharmacist verify the validity of the prescription using the finished product and the information you provide? |

Original prescription |

|

Can the pharmacist verify the patient information using the finished product and the information you provide? |

Original prescription, patient profile, patient, physician, or nurse |

Wrong patient given medication |

Can the pharmacist verify the correctness of the prepared prescription based on the medication information provided? |

Physical appearance of prepared medication, calculations and conversions of technician, original manufacturer’s container, pictographic medication verification programs, package insert |

Medication selection error made; incorrect dose, form, or formulation selected; incorrect medication administered |

IN THE REAL WORLD

IN THE REAL WORLD

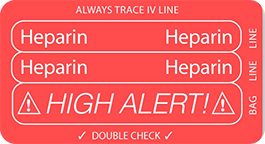

In the hospital setting, heparin is available in vials of concentrations from 10 units per mL to 10,000 units per mL. The lower concentrations are used to flush, clear, or maintain flow in an IV or dialysis line whereas the higher concentrations are used as adult blood thinners. Unfortunately, several serious medication errors, including death, have occurred when technicians and nurses have inadvertently selected the wrong heparin vial for patient recipients.

The FDA supported a USP proposal to revise the labels of Heparin Lock Flush Solution and Heparin Sodium Injection. The USP recommended that manufacturers clearly state the total drug strength by name and label call-out. Hospitals have also developed and implemented policies specifically for heparin administration. These policies include additional computer alerts, a a cross-check system between nurses, limited availability of certain concentrations on the nursing units, and colorful labeling to minimize heparin dosing errors.

Checking Other Technicians’ Work

A useful awareness exercise in considering what resources are needed for the pharmacist is to practice checking a colleague’s work. After trading a finished prescription or medication order with another technician, consider the following questions: Can you retrace the steps taken to fill the prescription or medication order? Can you validate all of the key pieces of information? Undertaking this exercise on a regular basis helps highlight bad habits or shortcuts that may open the door for medication errors. This is also practice for someday becoming a tech-check-tech supervisor.

Safety Alert

Safety Alert

The pharmacist must always check the technician’s work before a prescription is dispensed, though a tech-check-tech supervisor can do a first check.

Auxiliary Labels and Medication Guides

Patient and nurse education is obviously key to appropriate administration. Several auxiliary caution and warning labels may be applied for each prescription and need to be checked by the pharmacist. They need to be prioritized, on the container, however, so that the most important warning is seen first. For example, if an antibiotic that interferes with birth control and makes a patient sensitive to sunburn is being administered to a woman on birth control, it may be important to make the birth control interference most prominent with the sun warning next (unless the patient also has a history of skin cancer). Before the technician affixes the auxiliary labels to the prescription vial, they should ask the pharmacist which ones to prioritize.

Similarly, Medication Guides with boxed warnings should not just be stuffed into the patient’s prescription bag but should be stapled to the top of the bag so that they are in view. Common drugs that require an FDA-mandated Medication Guide are listed in Table 14.10. For more information, go to https://PharmPractice7e.ParadigmEducation.com/FDA-Common.

Step 8: Store Completed Prescription

Simple measures—such as establishing well-organized and clearly labeled storage, backup database, and temperature-controlled systems—can help keep a patient’s medications together and separate from those of other patients while being properly stored.

Well-Organized Storage Systems

Orderly storage decreases the chances that patients will receive someone else’s prescriptions or not receive their own because they were given to another patient. Off-site backup data storage systems are necessary in the event of natural disasters or fires.

Having stock shelves that are well lit and neatly and systematically organized makes it easier and swifter to find the correct medications.

Table 14.10 Examples of Drugs Requiring a Medication Guide

Drug |

Concerns Associated with Use |

|---|---|

ADHD drugs (such as Adderall XR, Ritalin) |

May cause heart-related problems (sudden death, stroke and heart attack in adults, increased blood pressure and pulse); mental health problems (thought problems, bipolar illness, aggressive behavior); circulation problems |

Amiodarone (Cordarone) |

May cause lung problems; may cause liver problems; may worsen heart problems |

Antidepressants (SSNRI such as fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, citalopram, escitalopram) |

May be associated with an increase in suicidal thoughts and actions (especially in children, adolescents, and young adults) |

Ciprofloxacin (Cipro) |

May cause tendon rupture; may cause nerve damage; may cause seizures |

Isotretinoin (Accutane) |

Causes birth defects and miscarriage in pregnancy; may cause serious mental health problems |

NSAIDs (such as celecoxib, diclofenac, ibuprofen, ketorolac, naproxen, sulindac) |

May increase the risk of heart attack or stroke that can lead to death; may increase the risk of bleeding and ulcers |

Transmucosal immediate-release fentanyl (TIRF) |

May increase the risk of overdose and death; only for use in patients with pain severe enough to require around-the-clock, longterm treatment with an opioid; patients must already be using a regular opioid medication upon initiation |

Warfarin (Coumadin) |

May cause bleeding; may interact with other medications and supplements |

Rivaroxaban (Xarelto) |

May increase the risk of bleeding during use; may increase the risk of blood clots upon discontinuation |

Zolpidem (Ambien) |

May cause memory loss of events and activities that take place shortly after consuming a dose |

Temperature-Controlled Storage Systems

As you know, failure to store medications properly with the correct temperature, humidity, and light-sensitive conditions may result in loss of drug potency or effects, which can cause serious harm. The following examples illustrate this:

Inadvertent freezing of certain types of insulin results in changes in the formulation. Once the drug has been thawed and administered, the body absorbs it differently, resulting in a less than desired effect.

Improper storage of nitroglycerin—a medication used to treat angina or chest pain—results in a loss of therapeutic efficacy. Nitroglycerin molecules adhere to plastics and cotton; therefore, sublingual tablets must be stored in original glass containers under airtight conditions without cotton.

Dornase alfa inhalation solution (Pulmozyme) is medication for cystic fibrosis that needs to be protected from light and stored under refrigeration. If exposed to light, the medication loses potency. Product stability is compromised if exposed to elevated temperatures for more than 24 hours.

Consistent checking of refrigerator and freezer temperatures in the pharmacy or on the nursing unit must be done frequently and be well-documented. Keeping a computer or written log of temperature checks is often a technician’s responsibility. However, any staff member accessing these storage areas should carefully monitor temperature and report any abnormal readings immediately.

If power is lost in any pharmacy setting for an extended period of time, such as after a hurricane, backup generators must be available or the drug inventory will need to be destroyed. Table 14.11 lists the information needed and the resources used to avoid potential errors in the eighth step of the prescription-filling process.

Table 14.11 Step 8: Store-Completed Prescription

Information to Check |

Resources to Verify Information |

Potential Errors Resulting from Failure to Check/Verify Information |

|---|---|---|

Are storage conditions appropriate for the medication (e.g., humidity, temperature, light exposure)? |

Package insert |

Medication becomes degraded |

Are each patient’s medications adequately separated? |

Physical review of medications placed in bags, boxes, or bins |

Patient receives medication not intended for them; patient fails to receive medication (i.e., omission) |

Are storage areas kept neat and orderly? |

Use of organizational systems (e.g., bins, boxes, bags, alphabetizing, numbering, consolidation) |

Patient receives medication not intended for them; patient fails to receive medication (i.e., omission) |

Step 9: Deliver Medication to Patient or Nursing Unit for Administration

At the point of delivery to a patient or administering nurse, opportunities for mix-ups arise. For instance, there may be medications for both Rachel C. Gonzales and Raquel V. Gonzales in the storage bins. Using a date of birth and/or an address, or a hospital patient bar code ensures that the correct medication is dispensed to the correct patient. Once the patient’s identity is reconfirmed, the technician needs to double-check the number of medications that the patient or the adminis tering nurse expects to receive.

The technician should verify the date of birth and/or the address of the patient and the name of the expected medication before presenting the drug to the patient.

Patients and nurses often notice something different from their expectations, and verifying the medication with them can serve as a triple-check. Errors—such as receipt of the wrong medications or missing medications (omission of therapy) as well as dosage form and administration errors—can be caught in this way. See Table 14.12 for safety tips for the ninth and final step.

Table 14.12 Step 9: Deliver Medication to Patient or Nursing Unit for Administration

Information to Check |

Resources to Verify Information |

Potential Errors Resulting from Failure to Check/Verify Information |

|---|---|---|

Will the appearance of any of the medications be new to the patient, caregiver, or nurse? |

Prescription label, patient, patient education handouts, patient profile |

Administration error made; patient nonadherent with medication instructions |

Is the patient receiving medications intended for them? |

Patient, caregiver, original prescription, patient profile, bar coding identification system |

Patient receives medication not intended for them; patient fails to receive medication (omission) |

Does the patient or caregiver understand the instructions for use? |

Pharmacist, patient education handouts, drug information resources |

Administration error made; patient nonadherent with medication instructions; drug interactions, adverse reactions, degradation of medication occurs because of improper handling or storage |

Does the patient, caregiver, or nurse know what to expect? |

Pharmacist, patient education handouts, drug information resources |

Side effects and adverse reactions occur; clinical effect not achieved |

Are all of the medications prescribed for the patient included? |

Consolidation of medications into one bag, bin, or box; use of organizational systems (e.g., bins, boxes, bags, alphabetizing, consolidation) |

Patient fails to receive medication (omission); therapy not completed |

Explanation of Medication to Medication Administrator

Before delivering a medication to a patient, be aware that counseling by a pharmacist may be required first. When it is appropriate to hand over the medication, remember to ask basic questions, such as “Do you understand why this medicine is being used and are you comfortable with how this medicine works?” and “Do you know how to take it?” (Most nurses are well aware of how the typical medications work but may be unaware of a new one.) Call attention to auxiliary warnings and caution labels on the medication bottle, and, if a Medication Guide is stapled to the bag, unstaple it and open it up to highlight key pieces of information. (If a required Medication Guide is not distributed, the pharmacy may receive heavy fines during an audit.) If the patient has questions, call the pharmacist over to answer them. The key information a patient must understand is listed on Table 14.13.

Your conversations and questions can uncover key information and provide essential guidance to the patient and the nurse.

Table 14.13 Information Patients Must Know About Their Medications

|

“Show-and-Tell” Technique with Patient In some community pharmacies, a “show-and-tell” technique is employed. The technician or pharmacist opens the vial, shows the drug product to the patient, and describes its proper use. This added step not only helps the patient identify the drug, but also provides an extra opportunity to check that the correct drug product was put into the vial. It also shows patients that you and the pharmacist really care, which helps them trust enough to listen carefully, follow directions more closely, and share key information. If the patient notices that a refilled drug looks different from a previously filled drug, the patient has a chance to point this out and have this discrepancy verified.

Safety Alert

Safety Alert

Pharmacy technicians are only permitted to review information on a medication’s label with a patient. If a technician suspects that a patient has questions or is in need of further counseling, the technician should alert the pharmacist.

In many cases, the correct drug was dispensed, but the prescription may have been refilled with a different generic drug, so the shape or color of the tablet or capsule differs, and you can explain this. The “show-and-tell” technique plus counseling will save a later telephone call to the pharmacy.

The technician is encouraged to use the “show-and-tell” followed by the “tell back” system to minimize patient administration errors. This process also ensures that the proper medication is being dispensed, as the patient will generally correct the technician if not.

“Tell Back” System Similar to the “show-and-tell” technique, the “tell back” system is recommended by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Tell back is a collaborative approach that uses patient-centered, open-ended questions to encourage the patient to repeat back what he or she understands. This method is especially useful for dispensing new medications or when providing medications to a new patient.

For example, you could say something like “Ms. Rodriguez, you are taking several medications for high blood pressure and cholesterol. I have given you a lot of information on the attached medication information sheets, including these Medication Guides. It would be helpful for me to hear your understanding of these medications and their side effects.” This line of questioning is preferred over the more common, closed-ended questioning like “Do you have any questions?” If you sense any lack of understanding, the pharmacist should be notified and the patient counseled.

Hospital Prevention Procedures

Upon delivery of medications to a nursing unit, you should determine if the appropriate nurse knows about newly prescribed medications and if the delivered medications were all that were expected. When medication carts are returned with unused, regularly scheduled medications, follow up to determine whether errors of omission occurred. Also, note any discrepancies in the nursing units’ automated drug dispensing machines between quantity counts of what should be present and what actually is present. Then you or the pharmacist can discuss the gaps with the nurses to discover the reasons and resolve them.

In the treatment of certain diseases, such as cancer, multiple drug therapy combinations are prescribed together because they work in concert to treat the disease. If a particular drug is missing from the drug therapy combination, treatment is incomplete, so each drug should be verified separately, not as a set. In addition, many of these drugs are extremely toxic, and any dosing error could be fatal. So all chemotherapy and hazardous substances must be triple-checked by the technician, the pharmacist, and the nurse.

Beyond the Pharmacy—Patient Self-Administration

Even with labels and a great deal of printed information handed to them, patients often make errors in the self-administration of their drug therapies for various reasons. Patients often contribute to medication errors by doing the following:

forgetting to take a dose or doses

taking too many doses

dosing at the wrong time

not getting a prescription filled or refilled in a timely manner

not following directions on how to take the doses and what behaviors to avoid with them (such as not eating certain foods or avoiding alcohol)

terminating the drug regimen too soon (which can be problematic with antibiotics)

Any of these actions may result in an adverse drug reaction or a subtherapeutic (less than desired effect)—or even toxic—dose. Not taking a prescribed medication could result in the progression of a chronic disease. Any of these circumstances could result in short-term or long-term harm, depending on the drug and the disease being treated.

Patient failure to follow medication therapy as the physician instructs is medication nonadherence, and it occurs because of many different personal and financial reasons. These include not having had medication information explained well, misunderstanding the instructions (perhaps because of inattentiveness, language barriers, or cultural barriers), not taking the instructions seriously, or not remembering to follow the directions.

Pharm Fact

Pharm Fact

As many as 50% of patients on essential long-term medications no longer take their medication after one year.

If there are cultural or language barriers, some actions can be taken to overcome these obstacles, which will be addressed in the next chapter. If forgetting may be an issue, you can suggest daily or weekly medication boxes and refrigerator magnet reminders. In cases where memory problems exist, educating the caregiver in addition to the patient is important. If other issues are present, alert the pharmacist or guide the patient to counseling.

When refilling a prescription, take note of the history from the computer profile. If the patient appears to be nonadherent with the prescribed medication, perhaps having gaps in refill timing, it is helpful to ask some questions to gain more information. Tactfully inquire if prescriptions have been filled at another pharmacy or via mail order, and, if so, add this to the medication profile.

However, all patients should be strongly encouraged to use only one pharmacy to lower the risks of serious medication interactions and errors because of lack of shared medication information. Patients should also be encouraged to talk to the pharmacist or call later if questions on proper medication use or unexpected or serious side effects arise after leaving the pharmacy. If using multiple pharmacies, problems with memory, or an improper understanding of label directions are not the causes of medication nonadherence (or you cannot help the patient resolve these issues), the gap(s) or problems in therapy should be brought to the attention of the pharmacist for follow-through counseling intervention.

Cost is often an issue for patients when they are not seeing their doctors, filling, or refilling their medications. If cost is an issue, technicians can help them find coupons, assistance, or insurance coverage, as noted in Chapter 8. If cost is a concern, the pharmacist should discuss less costly therapy options with the prescriber so that the illness or disease can be adequately treated.