14.5 Medication Error Reporting Systems

In most pharmacy settings, errors are reported internally and analyzed within the organization rather than being reported to a centralized external national database. Fear of punishment, of course, is always a concern when an error arises. As a result, healthcare professionals admit to not reporting an error when it is discovered, leaving the door open for the same error to occur again. For this reason, anonymous or no-fault systems of reporting have been established. The focus of no-fault reporting is on fixing the problem rather than on assigning blame.

Pharm Fact

Pharm Fact

The error rate for chain pharmacy personnel is generally less than 5 in 10,000 prescriptions. If a pharmacist or a technician is at or exceeds this rate, they are counseled and put on notice. If this error rate is repeated, termination may result.

The task of error reporting is generally performed by the pharmacist. However, pharmacy technicians are an integral part of the process of error identification, documentation, and prevention. An understanding of the what, when, where, and why of error reporting is important for pharmacy technicians as well as for pharmacists.

Telling Patients about Errors

An important piece of medication error reporting is the delicate task of informing the patient that a medication error has taken place to avoid a problematic drug reaction or stop the continuation of the medication problem. This is typically the pharmacist’s responsibility.

The circumstances leading to the error should be explained completely and honestly. Patients should understand the nature of the error, what (if any) effects the error may have, and how they can become actively involved in preventing errors in the future. If the medication error will lead to a side effect or adverse drug reaction or impact on the disease or illness being treated, the pharmacist must also contact the prescriber.

Pharmacy Safety Organizations

Several efforts have been made to create a safe and comfortable atmosphere for individuals to report medication errors. In 2005, Congress passed the Patient Safety and Quality Improvement (PSQI) Act dedicated to promoting a culture of patient safety and continuous quality improvement (CQI) in healthcare facilities, provider organizations, and pharmacies. The act promoted the creation of certified patient safety organizations (PSOs) that systematically and confidentially collect error information from various providers, analyze it, and sort it for trends. Then the PSOs communicate the information through a network of medication error databases along with recommendations for improvement. PSOs may be nonprofit or business entities, within healthcare systems or insurance companies.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

Generally speaking, people are more likely to forgive an honest error reported immediately upon recognizing it, but rarely accept concealment of the truth.

Hospitals have internal CQI programs for accreditation. Some community pharmacies work with outside companies such as Pharmacy Quality Commitment (PQC™). This company offers a quality improvement system specifically for community pharmacies to integrate error logging and analysis software and other resources to:

establish a quality-conscious work flow;

encourage adoption of a fair and positive safety culture;

identify, collect, and report quality related events (QREs)—medication errors that harm the patient, “near misses,” and unsafe conditions;

analyze the pharmacy’s QREs to identify process improvement opportunities;

improve work flow to decrease harmful QREs.

According to the PSQI, any information gathered in a PSO for the purpose of improving pharmacy patient safety is not admissible in criminal, civil, or administrative proceedings.

Many states have mandatory error-reporting systems, but most officials admit that medication errors are still underreported, mostly because of fear of punishment and liability. State boards of pharmacy do not punish pharmacists for errors as long as a good-faith effort was made to fill the prescription correctly. States such as Virginia, Florida, Texas, and California regulate, require, or recommend a CQI program to detect, document, and assess medication errors to determine the causes and to develop an appropriate response to prevent future errors. To avoid censure for self-reported errors, pharmacists in these states must indicate the steps that are being taken to eliminate weaknesses that might allow such errors to continue. Federally sponsored pharmacy programs encourage or require CQI programs for reimbursement.

Programs of the Institute for Safe Medication Practices

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) has been mentioned often as a leader in patient safety initiatives. It is a nonprofit healthcare agency whose membership is primarily composed of physicians, pharmacists, and nurses. The ISMP does not set standards but analyzes the causes of medication errors to communicate critical error-reduction strategies to the healthcare community, policy makers, and the public. It is a federally certified patient safety organization (PSO), providing legal protection and confidentiality for submitted patient safety data and error reports in its programs.

The ISMP has sponsored national forums on medication errors, recommended the addition of labeling or special hazard warnings on potentially toxic drugs, and encouraged revisions of potentially dangerous prescription writing practices. For example, the ISMP first promoted the now common practice of using the leading zero in pharmacy calculations. The Joint Commission has adopted many ISMP recommendations, including avoiding the use of common abbreviations such as “U” for unit or “IU” instead of international unit (which should be fully spelled out instead) and avoiding the use of the trailing zero when possible (such as lisinopril 5 mg, not 5.0 mg).

The ISMP disseminates information through email newsletters, journal articles, and video training exercises. In addition, the ISMP has both FDA safety and hazard alerts posted on its website at https://PharmPractice7e.ParadigmEducation.com/FDASafetyAlerts.

Medication Error Reporting Programs

The ISMP provides the national error-tracking programs called the Medication Errors Reporting Program (MERP) and the Vaccine Errors Reporting Program (VERP). These programs are designed to encourage healthcare professionals to voluntarily and anonymously report medication and vaccine errors (or near errors) directly. The ISMP shares all information and error-prevention strategies with the FDA. Reports can be completed confidentially online.

When reporting an error or hazard, include these key elements:

Tell the story of what went wrong or could go wrong, the causes or contributing factors, how the event or condition was discovered or intercepted, and the actual or potential outcome of the involved patient(s).

Be sure to include the names, dosage forms, and dose/strength of all involved products. For product-specific concerns (such as labeling and packaging risks), please include the manufacturer.

Share your recommendations for error prevention.

If possible, submit associated materials (such as photographs of products, containers, labels, prescription orders without the patients’ personal information) that help support the report being submitted.

Pharmacies have to consider their own systems for staffing, training, dispensing, organizing, storing, and controlling drugs to look for flaws in the systems and opportunities for improvements. The ISMP self-assessment safety checklists and HAMMERS can help.

Safety Assessment Initiative

The ISMP has also published an extensive report with a checklist of system-based safety strategies for pharmacy-related corporations, healthcare facilities, and community pharmacies, called “ISMP Medication Safety Self-Assessment for Community/Ambulatory Pharmacy.” The report’s recommendations include the following:

adequate pharmacist and technician staffing and training

appropriate ratios of pharmacists and technicians

review and verification by pharmacists of all information input by technicians

review of all medication alerts on dosing and frequency as well as contraindications or warnings about potential drug interactions

The report also emphasizes the importance of a nonpunitive internal reporting system to minimize future medication errors. The reporting system should include the following:

The order entry person should differ from the one who fills the order, thus adding an independent validation, or additional checks, to the order-entry process.

Pharmacy personnel should not prepare prescriptions from the computer-generated label in case an error occurred at order entry; they should use the original (or scanned copy) prescription.

Pharmacy personnel should keep the original prescription, stock bottle, computer label, and medication container together during the filling process; the pharmacist should verify dispensing accuracy by comparing all these with the NDC and/or bar code scan.

High-Alert Medication Modeling and Error-Reduction Scorecards

In addition to free safety assessment tools for institutional pharmacies, the ISMP also offers the High-Alert Medication Modeling and Error-Reduction Scorecards (HAMMERS™), which are free scorecard-based tools designed to help community pharmacies:

identify their own particular system and procedure/behavior risks related to dispensing certain high-alert medications

estimate how often the pharmacies commit an error or contribute to patients’ adverse drug events

HAMMERS can provide the most benefit when used to assess the risk errors of high-alert medications, which are those that have a high incidence of errors in all settings. Some high-alert medications include blood thinners (warfarin, enoxaparin), pain medications (hydro- and oxycodone with acetaminophen, fentanyl patch), the potent arthritis drug methotrexate, and several kinds of insulin. All chemotherapy and HIV drugs also fall into this category. These medications can produce serious injury or death to a patient if misused. Due to potential declines in diabetic patients’ blood glucose levels, insulin and oral hypoglycemics must also be carefully monitored.

The tool provides five scorecards, each assessing a type of error:

prescribing errors (such as wrong drug, dose, or directions)

data entry errors on patient (wrong patient)

data entry errors on drug (such as wrong drug, dose, or directions)

medication container selection errors (wrong drug or dose)

point-of-sale (POS) errors (medication dispensed to wrong patient)

By using the scorecards, pharmacies can estimate how often prescribing and dispensing errors reach patients and how the frequency will change if certain interventions are implemented. The scorecards can be found at https://PharmPractice7e.ParadigmEducation.com/HAMMERS.

The ISMP also publishes a list of common look-alike and sound-alike drugs that often contribute to medication errors—for example, Reminyl versus Amaryl. Reminyl is used to treat Alzheimer’s disease whereas Amaryl is used to lower blood glucose levels. The ISMP stresses awareness of such drugs and promotes adding a medical indication for each drug, as well as encouraging e-prescribing. To see the list, go to: https://PharmPractice7e.ParadigmEducation.com/ConfusedDrugNames.

Joint Commission Safety Initiatives and Reporting

Accreditation by the Joint Commission is, in part, dependent upon hospitals demonstrating a Sentinel Event Policy—an effective medical and medication error-reporting system through which all healthcare members may channel information confidentially. A sentinel event is an unexpected occurrence involving death, serious physical or psychological injury, or the potential for such occurrences to happen. When a sentinel event is reported, the organization (for example, a hospital, infusion pharmacy, or managed-care company) is expected to analyze the cause of the error (i.e., perform a root-cause analysis), take action to correct the cause, monitor the changes made, and determine whether the cause of the error has been eliminated.

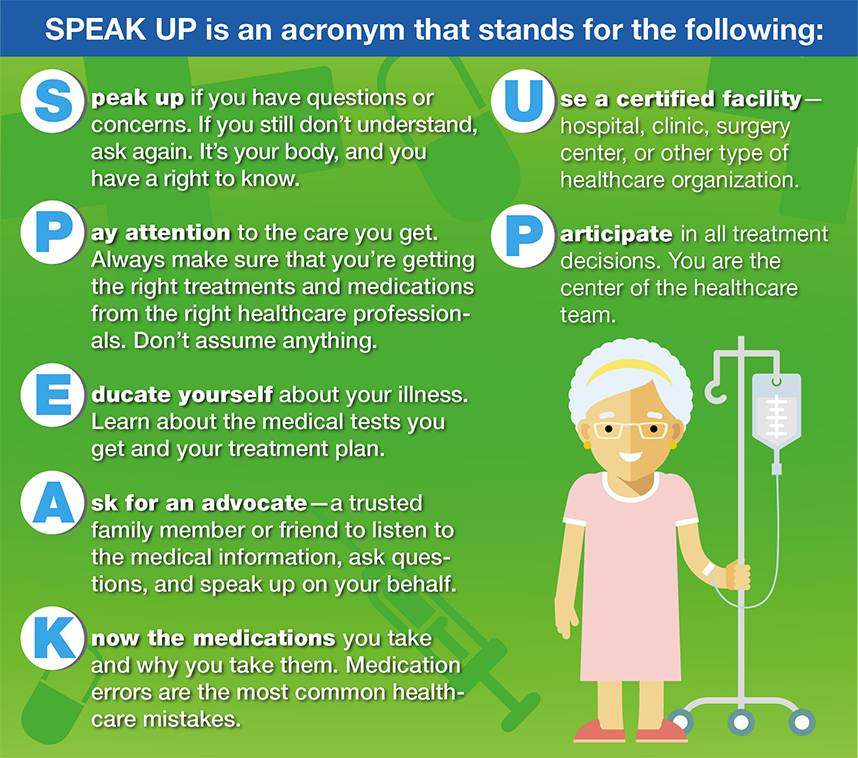

Figure 14.4 The SPEAK UP Program

The Joint Commission’s safety-related standards are based on the assumption that when a preventable medication error occurs, investigating the cause and making necessary corrections in policy or procedure are much more important than placing blame on an individual. Once the cause of the error is identified, a repeat medication error may be prevented in the future. Joint Commission standards also require that the hospital outline its responsibility to advise a patient about any adverse outcomes from the medical or medication error.

SPEAK UP Campaign for Patients

In concert with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the Joint Commission has developed an educational series of written brochures and videos for patients called the SPEAK UP campaign (see Figure 14.4). This program urges consumers to take a more active role in their health care and minimize misunderstandings that may lead to medication errors. The program has been adopted by many healthcare facilities for their patient education programs.

ASHP Initiatives

In response to health system medication errors leading to serious patient injuries and deaths, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) advocates for state laws to standardize technician certification. The organization emphasizes the need for pharmacy technicians to be trained in ASHP-accredited training programs and to be certified by the Pharmacy Technician Certification Board (PTCB).

US Pharmacopeial Convention (USP) Safety Initiatives

Many other professional organizations support patient safety efforts by gathering medical error information and using the data to create tools to support healthcare professionals in specific settings or situations. The USP supports two types of reporting systems for the data collection of adverse events and medication errors: the ISMP’s MERP (the national reporting program discussed earlier) and MEDMARX, an international reporting system.

MEDMARX Reporting System

The internet-based program MEDMARX allows institutions and healthcare professionals around the globe to anonymously document, analyze, and track adverse events such as medication errors and adverse drug events specific to an institution.

In a study of 26,604 medication errors reported to MEDMARX, the analysis found that:

more than 60% of these errors occurred during the dispensing process;

pharmacy technicians were involved in nearly 40% (38.5%) of the occurrences;

1.4% caused significant patient harm, including the deaths of seven patients.

Major contributing factors to the errors included distraction in the workplace, excessive workload, and inexperience.

Analyzing other trends in the error reports, the USP has addressed error prevention through medication labeling recommendations. For example, the organization established a new labeling standard to improve the safety of neuromuscular blockers in the surgical suites of hospitals. Such drugs now carry the label: “Warning—Paralyzing Agent.” For the chemotherapy drug vincristine, administered in the hospital and outpatient cancer clinics, the medication label now reads: “For Intravenous Use Only—Fatal if Given by Other Routes.” These labeling changes were a direct result of an analysis of voluntary reports of medication errors in MEDMARX.