1.2 The 20th-Century Evolution of Pharmacy Education and Practice

As the number of formalized pharmacy programs increased, the need for a pharmacy curriculum and practice standards did too. Within the last century, formalized practice and programs have evolved through four stages of development.

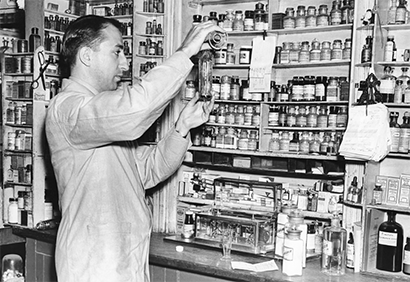

The Traditional Era of Compounding Pharmacists

During the first half of the 1900s, more than 80% of all prescriptions were compounded by pharmacists. For instance, Walgreens started out as a corner drug store in 1901, run by Charles R. Walgreen on the South Side of Chicago, selling medications and other valued retail items. With no formal pharmacy education, he had trained under prominent pharmacists to learn the science and art of compounding. Though one could study in a university pharmacy program, there were no educational requirements to take the pharmacist examination until 1920. As long as applicants completed a three- or four-year apprenticeship in a pharmacy, they were eligible for the exam. This is similar to the current situation for pharmacy technicians in some states.

Many pharmacy assistants worked alongside the pharmacists in apothecaries or small corner drug stores and hospitals, and they, too, received only on-the-job training. In the corner drug stores, pharmacy assistants also worked as cashiers and stocking clerks. During and after World War II, the need for hospital care for wounded soldiers increased the need for hospital drugs, pharmacists, and trained pharmacy assistants.

Prior to World War II, many pharmacists compounded their own preparations from oils, tinctures, and other essences from natural sources.

The American Society of Hospital Pharmacists (ASHP) formed during World War II to meet needs for standards and professional support particularly suited to hospitals, which included the need for trained assistants. Recognizing the volume of help required at the war front and in veterans hospitals, the US Department of Defense started formal training programs for medics and pharmacy technicians. After fulfilling the terms of their service, many military pharmacy medics became trained pharmacy technicians in nonmilitary hospital settings back home.

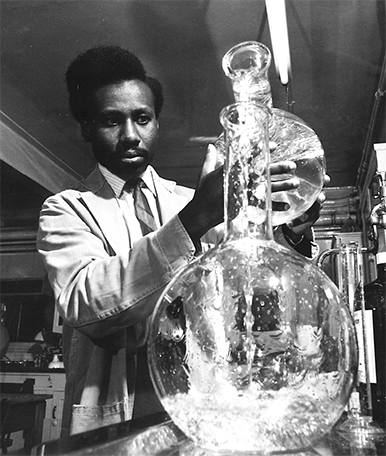

The Scientific Era of Drug Development

Following WWII and in the early 1950s, pharmaceutical manufacturers, such as Eli Lilly, Merck, and Pfizer, expanded laboratory research, leading to many new mass-marketed drugs (such as new antibiotics, hormones, vaccines, and cancer-fighting chemicals) in various dosage formulations. Companies began mass-marketing these laboratory drugs and making them available to corner drug stores.

Pharmacy Education

As drug production moved from the pharmacist’s shop to the assembly line, the pharmacist increasingly became more of a retail merchant selling premanufactured products. Consequently, pharmacists had to keep abreast and become much more knowledgeable about new drugs, their uses, side effects, and interactions—the emerging field of pharmacology. The necessity of a more formalized higher-education program for pharmacists became clear.

IN THE REAL WORLD

IN THE REAL WORLD

Pharmacy compounding is nearly a lost art. Of all prescriptions written, fewer than 1% are accomplished by hand compounding. The pharmacy personnel who work on compounding generally require specialized training in nonsterile, sterile, and hazardous compounding (see Chapters 10, 12, and 13).

Universities and colleges expanded their curricula and offered four-year degree programs that included prerequisite science courses. In addition to biology, physics, medicinal chemistry, anatomy, and physiology, pharmacists were required to complete courses in both pharmacognosy and pharmacology. Most courses were accompanied by work experience in an on-campus laboratory that often included a simulated pharmacy. Students also gained practical experience by working as interns in community and hospital pharmacies during summers and holidays. Both academic coursework and intern hours were required to take the state licensure examination.

In March 1944, this Pharmacy Officer in Teano, Italy, at the 8th Evacuation Hospital, is filling a soldier’s prescription. The US Department of Defense was the first institution to offer formal training for pharmacy technicians.

By 1960, a five-year Bachelor of Science Pharmacy degree (which included two years of pre-pharmacy course work and three years of professional studies) was the minimum standard for pharmacist programs in the United States. Additional science courses were developed and added to the pharmacy curriculum, including pharmaceutics—the study of how drug dosage formulations are manufactured and released in the body.

Pharmacy Technician Training

In a complementary way, the ASHP and the US Department of Health and Welfare were pushing for hospitals and junior colleges to begin training pharmacy technicians to continue the supply of educated pharmacy aides. In 1968, the first formal hospital training programs began. ASHP assisted in developing national program guidelines. The military and large university hospital pharmacies were early adopters of the pharmacy technician’s role, and these institutions still depend heavily on them today.

This 1955 image shows workers at the Eli Lilly and Company manufacturing unit carefully packaging and applying labels to the Salk polio vaccine vials, which were rushed to the childhood immunization program in order to stop the polio epidemic (discussed in Chapter 3).

The Education-Retail Gap

By the late 1960s, many US pharmacy students had begun to feel that there was a gap between their highly scientific schooling and the everyday realities of a community pharmacist. Until 1969, it was not considered ethical for a pharmacist to label the medication vials with the drug name or discuss the potential side effects of the medication with the patient. The pharmacist had to devote the bulk of their energies to completing routine tasks, running the business, and filling and dispensing drugs, rather than sharing information on drugs and interacting with patients and other healthcare professionals. To meet this educational gap, structured on-the-job internships gradually became more of a required component of pharmacy programs so that students also learned the job’s retail aspects.

As for pharmacy assistants in community settings, they were mostly aides attending to cashiering and stocking; few assistants had educational training and credentials. Trained technicians were generally employed in hospitals.

This pharmacy technician is working in the hospital pharmacy in London Hospital, Whitechapel, in 1968. Pharmacy technician training programs were just beginning in US hospitals.

The Clinical Era of Patient and Technician Education

In 1973, the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy established a study to consider the contemporary pharmacy mission. The 1975 Millis Commission report, Pharmacists for the Future, emphasized the role of pharmacists in sharing knowledge with patients and providers about drug use. The Millis Commission report (named after Dr. John Millis, the study director) led to a new focus on clinical or patient-oriented pharmacy. In this new clinical role, the pharmacist advises patients and healthcare providers about the appropriateness and effects of specific drugs.

This new role particularly suited the managed care model of healthcare, or health maintenance organizations (HMOs), that were gaining popularity in the 1970s and 1980s. In an HMO insurance plan, all the providers and facilities are under the oversight and salaried employment of the insurance company. The purpose of an HMO is to facilitate preventive care and overall health rather than have patients come in for emergencies; emergency care and hospitalizations are very costly in the short- and long-term, and often represent the worst-case scenario for a patient. HMOs found they could cut costs by developing their own best practice protocols and drug formularies, and utilizing group purchasing of drugs and medical devices.

HMO patient members primarily use the HMO’s staff providers, facilities, pharmacies, and drug lists, making it easier for healthcare professionals to share patients and information. In an HMO setting, physicians can work closely with clinically trained pharmacists to consult with patients on wellness counseling, drug therapy for pain and chronic diseases, and other prescribed drug therapies. Along with teaching hospitals, HMOs became the earliest implementers of the clinical care model for pharmacists. Early on, HMO specialty pharmacists were trained to provide services that often included education, ordering of laboratory tests, and adjusting patient dosages.

Work Wise

Work Wise

Cashiering may not be directly involved with healing, but ill patients and distressed family members particularly appreciate kind, understanding customer service as they are in states of worry, illness, or confusion over medications.

Hospital Pharmacy Technician Training

To free up time for hospital pharmacists to serve in this expanded role, formalized in-service training programs for pharmacy technicians were developed that focused on the preparation of medications. Technicians, following ASHP training guidelines, learned to assist in the preparation of sterile intravenous (IV) solutions—which are delivered directly as liquid medication in a patient’s vein—and fill medication orders without compromising patient safety. This allowed time for the specialty trained pharmacists to make daily hospital rounds with physicians, consult with patients, and monitor prescribed therapies.

Community Pharmacy Technician Training

Along with a push for training pharmacists for an expanded clinical role, there was a push for greater training of community pharmacy technicians. In 1979, the American Association of Pharmacy Technicians formed, and the Massachusetts College of Pharmacy began offering a pharmacy technician training program. In 1981, Michigan became the first state to use an examination to test the qualifications of a pharmacy technician.

This pharmacist brings a student from the College of Pharmacy at Arizona State University on patient rounds to learn patient care.

The Computer and Pharmaceutical Counseling Era

In the 1980s, computers were moving into pharmacy practice, replacing the typewriters of yesteryear. There was a slow learning curve as both pharmacists and technicians had to be trained on new hardware and software.

Over the last three decades, the software has greatly improved, with new innovations improving safety and productivity. Alongside pharmacy automation came the expansion of generic drugs and drug insurance programs. Prior to this, most drugs were brand name only and paid for in cash. With computerized entry of prescription orders and insurance billing information, the need for computer-educated and pharmacy-trained technicians grew even greater.

In 1990, Drs. Charles Hepler and Linda Strand built upon the Millis Commission report with a new framework for clinical pharmaceutical care; the report further expanded the professional mission to also include responsibility for counseling one-on-one with patients in choosing and using pharmaceuticals to ensure positive outcomes for drug therapy. The mission statements of many pharmacy organizations started to integrate this philosophy.

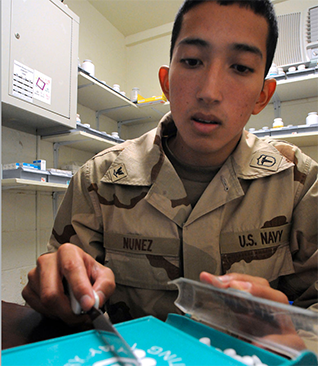

Navy Hospital Corpsman 3rd Class Esteban Nunez Ide, a pharmacy technician, counts out tablets for a naval patient’s prescription dosage.

More colleges of pharmacy adopted the six-year PharmD degree program (two years undergraduate science program and four years professional along with internships). New courses were developed, such as pharmacokinetics (individualizing doses of drugs based on absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion from the body), biochemistry (applying chemistry to biological processes), therapeutics, and pathophysiology. Therapeutics is the study of applying pharmacology to the treatment of illness and disease states, whereas pathophysiology is the study of diseases and illnesses affecting the normal functions of the body.

More schools of pharmacy, community colleges, and vocational schools began adding pharmacy technician programs. Illinois joined Massachusetts and Michigan in requiring an examination to become a pharmacy technician, and ASHP organized a national conference on the emerging role of the pharmacy technician in light of the changing role of the pharmacist. In 1989, the first conference for pharmacy technician educators was organized, followed by the formation of the Pharmacy Technician Educators Council (PTEC). PTEC not only offered instructor networking support but increasingly became a forum to develop and share a pharmacy technician curriculum, educational resources, and instructional materials. It continues this networking and support, advocating to increase the credentialing, recognition, and responsibilities of pharmacy technicians and leading the way in best technician practices.

As the pharmacy profession was expanding and evolving into many new areas, such as geriatric and mental health drug therapies, the American Society of Hospital Pharmacists (ASHP) was also broadening its organizational scope. In 1995 it changed its name to the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (still abbreviated ASHP). Since then it has represented the interests of pharmacists and pharmacy technicians for best practice in hospitals, health maintenance organizations, long-term care facilities, home care, and other components of healthcare.