2.3 History of US Statutory Pharmacy Law and Oversight

To fully understand the maze of laws, agencies, and organizations that oversee drugs and the field of pharmacy on federal, state, and local levels, one needs to know the history of how they evolved. The following sections highlight, in chronological order, the major statutory laws affecting the profession of pharmacy.

Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906

Beginning in 1820, the US Congress began depending upon the new pharmacy professional organization, the USP, for standardization of ingredients in drug formulations. However, problems persisted with the use of dangerous ingredients, false marketing claims, and inaccurate labeling. The purpose of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 was to address these problems and prohibit the sale or interstate transportation of adulterated or misbranded food and drugs. Labels could no longer legally contain false information about the strength or purity of the drugs. The act proved difficult to enforce, though, because the government had to prove that a drug was unsafe or contaminated, rather than the manufacturer having to prove that it was safe and pure.

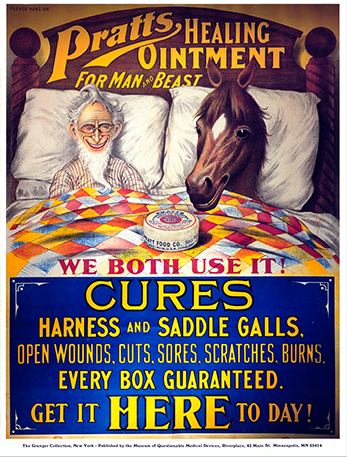

Marketers prior to the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act could make any claims they wanted to help sell their medications.

Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938

In 1937 more than 100 individuals died as the result of poisoning from a sulfa drug product that contained diethylene glycol, a toxic chemical used in antifreeze. The drug manufacturer, the S. E. Massengill Company, was unaware of diethylene glycol’s poisonous nature, and the drug was marketed without being tested in animals or humans. Because of this tragedy, the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FD&C) Act of 1938 was passed, becoming one of the most important pieces of legislation in pharmaceutical history. This legislation created the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), a new government agency to ensure that pharmaceutical manufacturers obtain approval before releasing any new drug. From this point on, manufacturers were required to file a new drug application (NDA) with each new drug and provide study data to show that the product was safe for use by humans.

Vials of imported blood thinner (heparin) from China were found to be counterfeits. Unlike the sterile vials shown here, these adulterated products were contaminated by chondroitin sulfate and resulted in 149 deaths from adverse drug reactions.

Unfortunately, this act did not require proof that a drug was effective or useful for the purpose for which it was sold. But the FDA did have the power to conduct inspections of manufacturing plants to ensure their compliance with safety and purity standards.

The act clarified the definitions of adulterated and misbranded drugs. An adulterated product became broadly defined as a product that differs from quality standards in drug strength, quality, or purity. For example, an adulterated product may be a prescription drug, over-the-counter (OTC) drug, or dietary supplement that is contaminated with other drugs or chemicals. The contaminating elements may or may not be harmful. For instance, certain dietary supplements have recently been found to be contaminated with other drugs, requiring their withdrawal from the market. Mail-order drugs from a Canadian website have been found to be manufactured in countries other than indicated, and adulterated with dangerous ingredients not labeled.

A misbranded product, on the other hand, is defined as a product whose label includes false statements about the identity or ingredients of the container’s contents. Pharmaceutical manufacturers have been found guilty and paid hefty fines for promoting “off-label” medical uses of approved prescription drugs. For example, a drug may be FDA approved for high blood pressure, but a manufacturer’s sales representatives may decide to promote its use to doctors for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease even though there is little or no scientific evidence to support that indication and no FDA approval for it. The FDA is as busy today as in 1938 in addressing the many challenges of drug adulteration and misbranding.

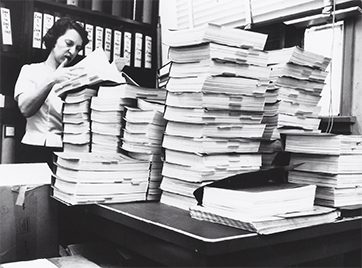

In the early 1960s, FDA chemist Lee Geismar helped review the studies for thalidomide’s new drug application. Here she is chest deep in assessing the research for another new drug.

Durham-Humphrey Amendment of 1951

The FD&C Act of 1938 was amended in 1951. The Durham-Humphrey Amendment established the distinction between so-called legend drugs (or prescription drugs that are labeled “Rx only” on the medication stock bottle), which require prescribers’ directions, and patent drugs (OTC, nonprescription drugs), which require only adequate manufacturers’ label directions. The prescription drug containers do not have to include “adequate directions for use” on their labels if instead they display the warning “Caution: Federal Law Prohibits Dispensing without a Prescription” and are accompanied by the required consumer information sheets from the prescriber and the manufacturer.

The amendment also authorized pharmacists to be able to take refill prescriptions for some substances over the telephone verbally rather than in writing. It set out guidelines as to which prescriptions can or cannot be refilled this way. Drugs with abuse potential were omitted to prevent false prescriber calls.

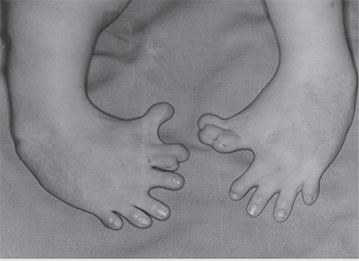

The effects of thalidomide on a child in the womb due to the mother’s intake during pregnancy caused extremely stunted growth in the child’s limbs before birth and afterwards.

IN THE REAL WORLD

IN THE REAL WORLD

Today, more than 80% of drug ingredients are manufactured overseas in a complex supply chain often beyond FDA jurisdiction. Contaminated, subpotent (less effective), or counterfeit medications can enter the supply chain at several levels, from the production of raw ingredients to the point of retail sale. In the recent past, a counterfeit version of Avastin (bevacizumab), a cancer drug, was imported and then pulled by the FDA from the market.

Adulterated cough medicines containing a toxin (interestingly, diethylene glycol again) were distributed in Panama, which resulted in many deaths. Subpotent counterfeit medications misbranded as real ones have occasionally been discovered in the United States as well, adversely affecting patient health. In response, the FDA has established agreements with over 60 countries to work together for drug purity and safety.

Kefauver-Harris Amendments of 1962

The Kefauver-Harris Amendments of 1962 were passed in response to the birth of thousands of infants—mostly in Europe—with severe abnormalities resulting from mothers who had taken a new tranquilizer called thalidomide while they were pregnant. The amendments required drug manufacturers to file an investigational new drug application with the FDA and provide in-depth drug-animal studies before initiating clinical trials in humans. The clinical trials had to prove that the drugs were not only safe for humans, but also effective. Once all the extensive trials were completed (typically taking 7–10 years) and the results proved that the product was both safe and effective, the manufacturer could then be granted FDA approval to market the product. To compensate for innovation and research costs, the government issued patent protection for brand-name products for a designated length of time.

Put Down Roots

Put Down Roots

A patent is a legal protection to the ownership and use in the marketplace of a specific drug formulation, invention, idea, brand name, or logo. Patent protection for drug formulations from copycat drugs and generics lasts 20 years, with some extensions for special cases.

Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970

The Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970, commonly referred to as the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), was created to combat and control drug abuse and to supersede previous federal laws regarding drug abuse. The act classified drugs with potential for abuse as controlled substances, or drugs that are restricted because of a risk for abuse and dependence. The controlled substances were then ranked into five levels of restriction, or schedules (see Table 2.1).

This controlled substance schedule, from most restrictive to least, continues to be used as follows:

Schedule I drugs are not commercially available or legally dispensed in the United States due to their high potential for abuse and addiction.

Schedule II drugs may be prescribed, but they are the most highly regulated drug category and no refills are allowed.

Schedule III, IV, and V drugs generally have progressively less abuse and addiction potential than Schedule II drugs, but they have quantity and time limits on refills.

Filling prescriptions for controlled substances requires great attention to the regulations for ordering, filling, documenting, storing, and disposal. The specific requirements and steps for dispensing controlled substances will be covered in Chapter 14, as well as mentioned in the chapters on community and hospital dispensing (Chapters 7 and 11, respectively). Technicians need to study and carefully practice these requirements.

The CSA paved the way for more concerted government efforts against addictive drugs. On July 1, 1973, President Richard Nixon used an executive order to establish the DEA. This order consolidated the multiple agencies that had previously been working against illegal drug use into a new agency in the Department of Justice. The DEA would serve to work within the nation and with other nations for what President Nixon termed “an all-out global war on the drug menace.”

The DEA classifies new drugs into the appropriate schedule (using data and input from the FDA and drug manufacturers). It also, at times, reevaluates drugs that have been on the market for some time to determine whether they should be changed to a scheduled drug. For example, there was concern about the overuse and abuse of the generic narcotic hydrocodone in combination products such as Lortab, Vicodin, and Norco. Consequently, the DEA reclassified these drug products from Schedule III to Schedule II in October 2014.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

Most controlled substance prescriptions are handwritten and signed by the prescriber. E-prescribing of controlled substances is also allowed, provided that both the prescriber and the pharmacy use DEA-approved software. In an emergency situation, a prescriber may phone in a C-II prescription, but a physical prescription must be provided within 7 days.

Table 2.1 Drug Schedules Under the Controlled Substances Act of 1970

Schedule |

Manufacturer’s Label |

Abuse Potential |

Accepted Medical Use |

Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

I |

C–I |

Highest potential for abuse |

For research only; must have license to obtain; no accepted medical use in the United States |

heroin (diacetylmorphine), lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), tetrahydrocannabinols (THC) |

II |

C–II |

High possibility of abuse, with use potentially leading to severe psychological or physical dependence |

Dispensing severely restricted; cannot be prescribed by telephone except in an emergency; e-prescribing allowed with DEA aproved authorized digital signature; no refills on prescriptions |

morphine; oxycodone; meperidine; hydromorphone; hydrocodone combination products (hydrocodone combined with acetaminophen, aspirin, or ibuprofen); fentanyl; methylphenidate; dextroamphetamine |

III |

C–III |

Moderate to low potential for physical and psychological dependence |

Prescriptions can be called in and refilled up to five times within six months if authorized by physician |

codeine combination products (codeine combined with acetaminophen, aspirin, or ibuprofen); ketamines; anabolic steroids |

IV |

C–IV |

Low potential for abuse and low risk of dependence |

Same as for Schedule III |

benzodiazepines, phenobarbital, carisoprodol, tramadol |

V |

C–V |

Lower potential for abuse than Schedule IV and consist of preparations containing limited quantities of certain narcotics |

Some sold without a prescription, depending on state law; if so, purchaser must be over age 18 and is required to sign a log and present a photo ID |

liquid codeine combination cough preparations, diphenoxylate/atropine, pregabalin |

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

While medical cannabis (or marijuana) is legal in many states, it is still illegal under federal law. At the time of publication, most cannabis products were considered Schedule I by the DEA. This is an example where federal and state laws differ.

Individual states may have additional guidelines for the prescribing and dispensing of controlled substances. State boards of pharmacy may advocate to their legislatures to reclassify prescription drugs as scheduled drugs or move a scheduled drug to a more restrictive schedule level to curb drug abuse in their region. Oral nasal decongestants, such as those containing pseudoephedrine (Sudafed) and ephedrine, and cough medicines containing codeine are available in most states as restricted OTC drugs. In other states, they may be registered as Schedule III drugs. As noted, the strictest rule always applies because that is the best way to protect the public health in a region and in the nation as a whole. All laws are written to set out only the minimum standard for safety, not the highest and most restrictive. If there is cause to have a more restrictive law in a specific state or the nation, then that rule overrides all.

In pharmacies, prescription drugs and select OTC drugs must be stored in a locked and secured area, with a pharmacist always on duty during facility open hours.

The Controlled Substances Act was also significant as it determined who may have the authority to prescribe controlled substances. Prescribers must now be authorized and monitored by the DEA jurisdiction in which they are licensed. Practitioners who may be licensed include physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners (advanced practice nurses), dentists, veterinarians, podiatrists, and psychiatrists. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners working under the direct supervision of a collaborating physician can also prescribe some controlled substances under the supervising provider’s DEA number.

In all cases, prescriptions must be written for a legitimate medical purpose based on the practitioner’s professional practice. For example, a dentist may write a narcotic prescription for dental pain but not for back- or cancer-related pain. A prescription for some controlled substances from a foreign physician (for example, a practicing physician in Canada or Mexico) cannot be filled in the United States because the prescriber must have a DEA license, which is available only to licensed prescribers in the United States. In addition, some pharmacies may not be licensed to fill a Schedule II prescription written by an out-of-state physician without verification, even if the prescriber has a valid DEA license.

Safety Alert

Safety Alert

For non–child-resistant containers, technicians should remind patients to place these medications out of reach if young children live in or visit their homes.

Poison and Prevention Packaging Act of 1970

To prevent accidental childhood drug poisonings, the Poison Prevention Packaging Act was passed in 1970. This act, enforced by the Consumer Product Safety Commission, required that most OTC and prescription drugs be packaged in child-resistant containers that cannot be opened by 80% of children under age 5, but can be opened by 90% of adults. Upon request from a patient, a drug may be dispensed in a normal container. In fact, the patient—not the prescriber—can make a blanket request that all drugs be dispensed to them without child-resistant containers. This blanket request is often made by older patients and those with severe rheumatoid arthritis. Medications commonly dispensed in non-child-resistant containers include the antibiotic azithromycin (or Zithromax Z-pak), Medrol Dosepak, birth control pills, sublingual nitroglycerin tablets, and metered-dose inhalers.

Unless specifically requested by the customer, medications are dispensed in child-resistant containers to prevent accidental poisonings

Drug Listing Act of 1972

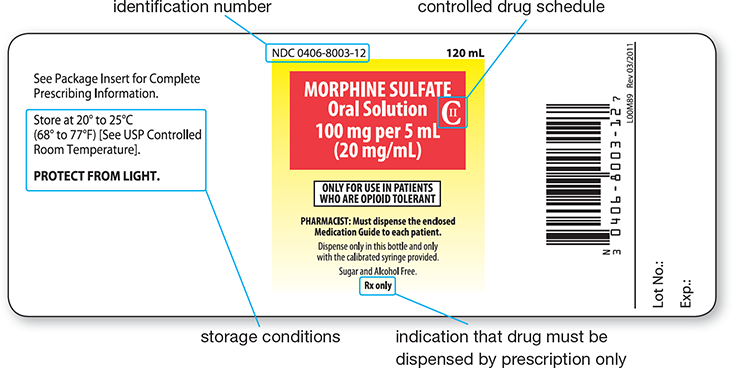

The Drug Listing Act of 1972 gave the FDA the authority to compile a list of currently marketed drugs and assign them each a numbered code. Every new drug is also assigned a unique and permanent product signifier known as a National Drug Code (NDC) number. It consists of 10 or 11 characters that identify the manufacturer or distributor, the drug formulation, and the size and type of its packaging, in that order.

The FDA requests—but does not require—that the NDC number appear on all drug labels, including the labels on prescription containers (see Figure 2.1). Using this code, the FDA is able to maintain a database of drugs by use, manufacturer, and active ingredients. It can track newly marketed, discontinued, and remarketed drugs. This barcoded information is widely used today to double-check the accuracy of prescriptions filled by automation. Insurance companies also use the NDC number in processing pharmacy reimbursements.

Figure 2.1 Manufacturer Drug Label

Orphan Drug Act of 1983

An orphan drug is a drug that is intended for patients suffering from a rare disorder (a condition that affects fewer than 200,000 people). Because developing and marketing these kinds of drugs can be prohibitively expensive, the Orphan Drug Act of 1983 provides the manufacturers tax incentives and grants them a longer time period to have the exclusive licenses to market these drugs. The FDA also moves these drugs faster through the approval process to get them swiftly to patients in need.

Since 1983, more than 500 orphan drugs have been FDA approved for treatment of rare diseases, most of which involve a genetic defect. For example, cystic fibrosis (CF) is a genetic disease that affects the lungs and other organs and often leads to premature death. With the act’s support of orphan drugs, CF patients now have treatments available for an improved quality of life and a longer life span. Another group of orphan drugs—statins—were initially developed in 1985 in response to a rare genetic defect known as homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Today, statins are commonly prescribed medications for millions of patients with high cholesterol levels.

Work Wise

Work Wise

Patients often become frustrated by the confusion over generic and brand-name drugs. Listening to their concerns and explaining the differences and similarities can help them better understand their medications.

IN THE REAL WORLD

IN THE REAL WORLD

Cystic fibrosis (CF) affects approximately 1 in 10,000 people. In people with CF, a special protein (called the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator) does not work correctly. The dysfunctional protein is unable to help move chloride—a component of salt—to the cell surface. This allows mucus in various organs—especially the lungs—to become thick and sticky. Drug treatments with special aerosolized antibiotics, biotechnology agents, and pancreatic enzymes to assist in digestion have markedly improved the life expectancy of patients with CF. There are over 50 orphan CF drugs, including Pulmozyme (dornase alpha) and aerosolized tobramycin. The financial incentives, patent and legal protections, and accelerated FDA approvals resulting from the adoption of the Orphan Drug Act allowed for the development of these drugs. Visit https://PharmPractice7e.ParadigmEducation.com/Orphan for more examples.

Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 (Hatch-Waxman Act)

Prior to the 1980s, drugs with brand names were the ones most prescribed, dispensed, and recognized by prescribers and patients. The proliferation of brand name drugs was the result of many state anti-substitution laws passed to combat similar but counterfeit drugs. However, by 1984, mounting pressure by lawmakers, pharmacists, and consumers to reduce healthcare costs led to the passing of the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act. This legislation, also known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, streamlined the process to approve equally effective drugs with nonproprietary names, or generic names.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

More than 80% of prescriptions dispensed in community pharmacies are generic drugs. Generic drugs can be substituted for the related brand name drug in every state—unless the prescriber writes “brand only” or “do not substitute.”

Generic drugs are required to be comparable to their brand-name counterparts in intended use, quality, performance, safety, strength, route of administration, and dosage form. Since the original drug manufacturers handled the research studies, and the brand name drugs established a public track record of safety, the generic drugs are not required to go through the same rigorous scientific review for safety and effectiveness. However, they must demonstrate bioequivalence (similar strength and outcomes) to the brand-name product. (The concept of bioequivalence will be discussed in detail in Chapter 3.) The growth and expansion of generic manufacturers can be traced to the Hatch-Waxman Act.

The rise in availability of cheaper, generic drugs was due in part to the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984.

The Hatch-Waxman Act also extended the length of the proprietary patent licenses for the brand-name drugs. The extended patent protection time allows the manufacturers to recoup the research and development costs, providing an incentive to research new drugs.

Once the patent expires, any manufacturer is allowed to copy and market a competing generic drug, which is clearly much less costly than developing the original. Since medications are labeled by both their generic names and their brand names (and, at times, by their chemical names), pharmacy personnel, including technicians, must be familiar with the various names for the related medications. (See Table 2.2 for examples of the different names for bioequivalent medications.)

Table 2.2 Different Names for One Drug

Type of Name |

Drug Name |

|---|---|

Chemical name |

p-isobutylhydratropic acid |

Generic name |

ibuprofen |

Brand name |

Advil, Motrin, Motrin IB |

Prescription Drug Marketing Act of 1987

Manufacturers distribute drugs through large distributors, which then work through smaller regional and state distributors and warehouses. Independent distributors and warehouses can purchase their own drug supplies to store for times of local shortages in the regular distribution system or to sell independently. Problems arose in this system. For example, foreign counterfeit drugs were being sold as brand name drugs by independent companies, and some distribution companies were taking their foreign sales returns and selling them in the United States. Unethical sales representatives were taking drug samples meant for providers and distributing them as prescription products. Warehouses were selling products at wholesale prices, undercutting the safe processes of pharmacy dispensers.

Pharm Fact

Pharm Fact

In 2014, Congress passed the Designer Anabolic Steroid Act, which added numerous new substances to the anabolic controlled substances list originally created in the 1990 act. The new bill also added serious penalties for mislabeling steroids to avoid detection.

Due to concerns over the safety and competition issues raised by these secondary distribution markets, the Prescription Drug Marketing Act of 1987 required that all drug wholesalers be licensed by the states. The act also prohibited the sale, trading, or distribution of drug samples to persons other than those licensed to prescribe them. The reimportation of a drug into the United States by anyone except the manufacturer was prohibited as well.

Drug reimportation continues to be a political and economic issue. For example, many citizens travel across the Canadian border to fill their prescriptions or receive their prescriptions through the mail from Canadian drug wholesalers. US pharmaceutical manufacturers have threatened to reduce the supply of drugs to Canada if the practice of illegal reimportation to the states continues. Many Canadians also are concerned, fearing medication shortages and the abuse of prescription drugs within their own country from lax mail-order companies. The Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 (discussed later in the chapter) has helped to mitigate but not eliminate the drug reimportation problem—it adopted and has encouraged participation in Medicare Part D drug insurance plans, thus lowering costs to seniors, who are a major market for Canadian drugs.

IN THE REAL WORLD

IN THE REAL WORLD

The dispensing of generic drugs has been a major factor in containing the high cost of pharmaceuticals, with savings ranging from 30% to 80% of brand-name counterparts. In 2012, US patients together saved $193 billion dollars by using generics, though generic prices are now rising exponentially. Although generic drugs are considered similar and effectively equal to brand drugs, it is important to realize that they are not exactly the same. FDA criteria require that the medically active ingredients found in the bloodstream after use must not be much less or more than 5% of the amount found after the brand-name drug. However, the added ingredients in generic drugs can be different and often are, and these ingredients can affect the drug’s responsiveness in different patients. How quickly or slowly the drug acts can also vary.

Consequently, providers, pharmacists, and pharmacy technicians must understand that generics are not precise replicas of the brand name drugs. Patients should be careful to watch for specific outcomes and side effects to make sure that they have the right drug for their needs.

Anabolic Steroids Control Act of 1990

Anabolic steroids, or synthetic drugs that mimic the human hormone testosterone, have become widely known due to their misuse by popular professional athletes. These steroids are used to build muscle mass, enhancing the strength—and, ultimately, the performance—of the users. Anabolic steroids have a long list of serious adverse effects and can cause permanent damage. Prior to 1990, these drugs were illegally manufactured, imported, and sold on the black market. However, there were no stiff criminal penalties. Some anabolic drugs were included as ingredients in loosely regulated dietary supplements. Congress passed the Anabolic Steroids Control Act of 1990, which designated anabolic steroids as a Schedule III class of drugs on par with codeine. This provided regulated prescriptive access to patients who needed the steroids for pain or other uses while allowing the FDA to enforce steroid drug standards, confiscating and prosecuting those responsible for illegal use, product distribution, and imports.

To help enforce the Anabolic Steroids Control Act, many professional sports organizations employ random drug testing. Since anabolic steroids are Schedule III drugs, prescriptions for these steroids—such as testosterone gels, patches, and injections—can be refilled a maximum of only five times or for up to six months from the date written, whichever comes first. This is similar to regulations for many nerve and sleep medications.

This FDA educational poster warns about the dangers of steroids.

Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990

To help address the rising costs of pharmaceutical expenditures for Medicaid, the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 (OBRA-90) required that, in order to receive Medicaid funding, each state had to establish a Drug Utilization Review (DUR) Board. The board’s job has been to establish a state Medicaid preferred drug list and set standards for pharmacist-to-patient education and counseling. The act also required that pharmacy personnel engage in “a review of drug therapy before each prescription is filled or delivered to an individual . . . typically at the point of sale. . . . The review shall include screening for potential drug therapy problems due to therapeutic duplication, drug-disease contraindications, drug-drug interactions (including serious interactions with nonprescription OTC drugs), incorrect drug dosage or duration of treatment, drug-allergy interactions, and clinical abuse/misuse.” OBRA-90 made the DUR and medication management therapy (MTM) a necessity for Medicaid patients, setting a standard for other patients as well.

Barry Bonds, apparently under the influence of anabolic steroids, hit more career home runs than any other player in baseball history. However, he did not receive the Baseball Hall of Fame award his first year of eligibility because he was convicted in 2011 (upheld in 2013) of obstructing justice by denying knowledge of his steroid use.

For these services, pharmacists need accurate records and information. OBRA-90 required pharmacy personnel to make reasonable efforts to collect, update, and record all pertinent patient information and medication history. A pharmacist must review the patient profile before filling each prescription and then offer to provide drug therapy screening and medication counseling. This offer must be documented, noting whether the counseling was accepted or refused. Technicians often handle or assist in this documentation process.

Work Wise

Work Wise

Many patients take drugs for granted without understanding their real effects. They do not understand the value of medications. Informed technicians can help explain some of these benefits while directing them to pharmacists for medication counseling.

Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994

The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act was passed in 1994. It provides definitions and guidelines on dietary supplements, including vitamins, minerals, herbs, and nutritional supplements. This legislation states that supplement manufacturers—unlike those of prescription and OTC drugs—are not required to provide proof of efficacy or standardization to the FDA. The manufacturers simply have to prove consumer safety and make truthful claims. The labels and marketing may not make claims of curing or treating ailments; they may state only that the products are supplements to support health.

Safety Alert

Safety Alert

The FDA does not regulate dietary supplements for purity or safety unless problems have arisen.

While dietary supplements are sold alongside nonprescription drug products, many consumers think that they go through the same approval processes and rigor in their regulatory oversight. Pharmacy technicians should be prepared to explain the significant distinctions. The FDA may only review false claims of supplements and monitor safety issues that have arisen in public use and statements. If claims of medical treatments or miracle cures are made, the FDA can require manufacturers to provide scientific research and proof, similar to requirements for prescription and nonprescription drugs. Still, some manufacturers manage to tweak the verbiage of their labels to skirt this regulation—for example, using the tagline “for a healthy heart” rather than “to lower cholesterol.”

If the FDA does want to remove a dietary supplement from the market for safety reasons, it may do so. However, it must first hold public hearings, and the burden of proof is upon the FDA to demonstrate that the dietary supplement is unsafe. The drug ephedra, or its herbal counterpart ma huang, was an ingredient in many weight-loss products. In 2004, the drug was removed from the market by the FDA as a result of multiple reports of serious adverse reactions and some deaths. The following year, the lower courts overruled the FDA’s action, but in 2006 the Court of Appeals upheld the FDA action, thus removing all ephedra products from the US market.

IN THE REAL WORLD

IN THE REAL WORLD

In 2015, the FDA withdrew the Pyrola Advanced Joint Formula dietary supplement as it was found to be contaminated with diclofenac (a prescription pain and anti-inflammatory drug) and chlorpheniramine (an antihistamine). The FDA publishes a comprehensive list of dietary supplement withdrawals on its website: www.fda.gov.

More recently, the FDA has warned consumers of fraudulent claims made for “all natural” weight-loss supplements. Claims such as “magic pill,” “melt your fat away,” and “diet and exercise not required” should raise red flags. Several of these products have been found to be tainted with weight-loss prescription drugs. Thus, they are potentially dangerous and considered misbranded by the FDA. Within the past 20 years, more than 40 weight-loss products have been withdrawn from the market.

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996 included many provisions that directly affect all healthcare facilities and personnel, including pharmacy technicians. One provision is to ensure the portability of moving health insurance from one employer to another, as indicated by the act’s name. So an emphasis was put on being able to communicate medical records electronically, using national codes for prescribers and pharmacy providers.

Perhaps the greatest effect of HIPAA on pharmacy technicians regards the handling of medical records, including personal prescription profiles. HIPAA placed safeguards to protect the confidentiality of patient health records. All healthcare facilities must provide a document to each patient that states the data privacy policy. It must also collect and save evidence of the patient’s acknowledgment that the HIPAA privacy document was received.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

Every new patient should receive and sign a copy of the pharmacy’s Privacy Agreement to be in compliance with the HIPAA statute. All patients need to re-sign it annually. Technicians often provide this form.

Pharmacy personnel, including technicians, also must follow certain protocols for assembling and organizing patient profiles, andv, under penalty of law, take care not to reveal any information about any patient outside the pharmacy workplace. They may not discuss or transmit prescription data to anyone other than the patient, parents of children under 18, and appropriate healthcare providers. Every pharmacy must train its employees on patient data privacy, and this training must be renewed on an annual basis. Failure to comply with HIPAA regulation is grounds for immediate termination. (For more information, see Chapter 15.)

Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997

The 1997 Food and Drug Modernization Act was enacted to update drug approval processes, streamlining them to accelerate the time until the release of newly patented and manufactured drugs. It also necessitated that the FDA regulate medical devices and required that biological drug products go through similar new drug approval processes.

Pharm Fact

Pharm Fact

The 2005 Patient Safety and Quality Improvement (PSQI) Act promoted mechanisms for patient safety and continuous quality improvement in healthcare facilities. It encouraged the creation of Patient Safety Organizations (PSOs) that can collect confidential information on medical errors to develop systematic changes for safety.

Before this act, no specific federal or state laws governed the practice of small-batch pharmacy compounding. One provision of this legislation allows pharmacists to compound nonsterile (and/or sterile) medications for individuals if these medications meet established USP standards. This allows the compounders to skip the intensive FDA requirements for newly manufactured drugs so that they can offer more personally tailored prescription products for people with special concerns (such as pediatric and geriatric patients) and health conditions (such as severe allergies). The act outlines major situations where pharmacists or small-scale facilities do not have to adhere to the large-scale Current Good Manufacturing Practices, product labeling directions for use, or drug approval applications. These exceptions do not undermine the safety and efficacy of compounded products (p.52), but simply allow pharmacies to create personalized drugs for individuals and small groups of patients with specific needs.

THE Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act also updated prescription drug labeling. Products labeled with “Caution: Federal Law Prohibits Dispensing without a Prescription” were changed to read “Rx only.” The law also authorized fees, paid by the applicant drug manufacturer, to be added to a new drug application to provide additional resources to the FDA to process and accelerate the review and approval of new drugs.

Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003

The Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act, also called the Medicare Modernization Act (MMA), updated the Medicare system and initiated the option of a prescription drug insurance program, called Medicare Part D, especially suited to patients with economic hardships or patients needing high-cost medications. The MMA also launched the Medicare Part C program, or the Medicare Advantage program, as a comprehensive healthcare insurance program option. Pharmacy technicians must be knowledgeable about Medicare programs since technicians are often involved in educating patients on their options.

The MMA and Medicare Part D encourage pharmacists to provide—and get reimbursed for—annual in-depth reviews of the medication profiles and ongoing therapies of Medicare patients taking high-cost medications or experiencing certain chronic health conditions. The purpose of this review is to add a safety feature to prevent adverse reactions and drug interactions (and costly hospitalizations) and to have the pharmacist look for ways to reduce medication costs. A lesser-known MMA provision allows for the development of health savings accounts for patients under age 65. This will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 8 on insurance.

Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act of 2005

Because common OTC ingredients are used to illegally manufacture methamphetamine (known as meth)—a highly addictive stimulant—Congress passed the Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act. The act reclassified all products containing the chemical pseudoephedrine (PSE) and ephedrine, found in products such as oral and nasal decongestants and combination sinus and allergy medications. It restricted the amount that can be purchased at one time or in any 30-day period.

These are just a sampling of the over-the-counter drugs containing pseudoephedrine and/or ephedrine that are restricted by the 2005 Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act.

All PSE products are now required to be stored behind the counter, and the purchaser has to present legal identification for purchase. The legislation also dictated that a log must be kept of all sales of PSE products and that all pharmacy employees, including technicians, had to complete a training program for the handling of PSE products. The DEA works with state agencies to enforce this act. (For additional information and procedures for the pharmacy technician to legally sell these OTC products, see Chapter 9.)

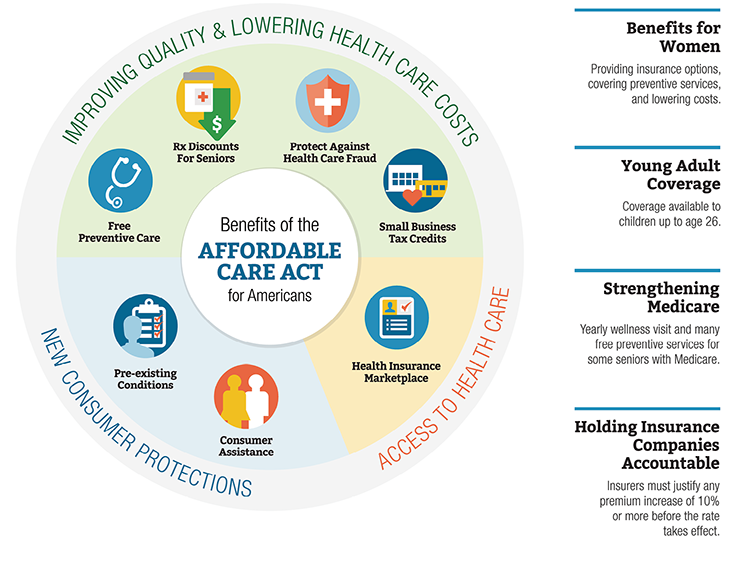

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, commonly known as the Affordable Care Act (ACA), mandated healthcare coverage under threat of personal penalties for all US citizens (see Figure 2.2). The ACA increased access to healthcare for more than 32 million uninsured citizens and individuals with preexisting medical conditions who were previously declared uninsurable. It required states to provide health insurance options to those who were not covered, with federal funding assistance to those who needed it, and to offer catastrophic insurance coverage for individuals with high-cost illnesses.

Work Wise

Work Wise

Patients and customers often share strong thoughts about politics and healthcare when talking to pharmacy personnel. To be professional, listen carefully but refrain from voicing a personal opinion. Choose your words carefully and respectfully, sticking to the facts of pharmacy practice.

Each state plan funded by the ACA must provide patients with a preferred drug list. This list helps ensure that patients are aware of which drugs are covered by their insurance and which are not. This is an area where medication therapy counseling from a pharmacist is particularly useful and often crucial.

The ACA also allowed healthcare systems and physician groups to form pilot healthcare teams, or Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), to serve Medicare Part D patients and to study team effectiveness in patient health outcomes and cost reductions. ACOs are groups of prescribers, pharmacists, and other providers, hospitals, and healthcare facilities that work together in a coordinated manner to seek out measurable improvements in patient outcomes. ACOs must include pharmacists, and each provider in the ACO must have full access to patient records so that they can communicate with each other for integrated patient care. ACOs are models of cooperative practice agreements. Technicians, especially advanced or specialist pharmacy technicians, often assist by helping assemble medication histories and by doing medication reconciliation, insurance formulary reconciliation, and medication assistance advocacy.

Studies are ongoing on the cost-benefit ratios to of the ACA different sectors. In 2015, the Supreme Court upheld the legality of the ACA. However, legal battles continue surrounding the ACA. Additional healthcare reform measures are being considered by government agencies, healthcare specialists, and all political parties.

Drug Quality and Security Act of 2013

The Drug Quality and Security Act (DQSA), also known as the Compounding Quality Act, passed as a result of a contaminated medication that was compounded in 2012 by a small Massachusetts facility and then widely distributed to out-of-state physicians’ offices, resulting in numerous patient deaths and injuries in a total of 20 states. Prior to this act, the regulatory oversight of small-batch medication compounding was handled solely by the states in which the substances were compounded and their pharmacy boards.

The overall goal of the DQSA is to better protect patients from drugs contaminated in the compounding process and sold in a different state, as well as to provide protection from counterfeit or stolen drugs. It established an electronic tracking system to trace drugs from ingredient sources through compounding and distribution processes. This tracking improves the ability to detect and swiftly remove harmful drugs from the public. The DQSA states that all small-scale pharmaceutical production should be compounded by a licensed pharmacist in a registered outsourcing facility. The facility must follow all state pharmacy requirements, and it is encouraged to register annually with the FDA as well, designating the pharmacist-in-charge and paying a fee.

Figure 2.2 Key Features of the Affordable Care Act

Content created by Assist. Sec./Public Affairs - Digital Communications Division

The compounding facility, however, must still comply with the Current Good Manufacturing Processes outlined by the USP and be subject to inspections by the FDA or its agents. When sterile processes are required, cleanroom standards must be followed in terms of facilities and procedures. Every six months, the pharmacy must report all the drugs and ingredients that were compounded to the Department of Health and Human Services and immediately report any adverse reactions from the pharmacy’s compounded medications to the FDA. However, registration with the FDA is voluntary and costly to compounding facilities due to the terms of the legislation.

The New England Compounding Center sold a fungus-tainted, injectable steroid to healthcare facilities throughout the United States, resulting in deaths and injuries. It took the FDA 684 days to collect the information to warn providers to pull the medication, prompting the enactment of the DQSA.

Many problems have still not been eliminated. In 2013, a New Jersey compounding pharmacy, Med Prep Consulting, was temporarily shut down for mold found in injectable pharmaceutical solutions. To enhance consistency in patient safety, all states need to mandate that all compounding activities be in compliance with USP standards on sterile and nonsterile compounding. Also, all pharmacy personnel must be educated, certified, and licensed, plus have specialty training and certification in sterile compounding and aseptic technique. Texas led the way in 2015 by requiring that all pharmacy technicians, who already must be certified to practice, have additional certification in sterile processing and aseptic technique.

IN THE REAL WORLD

IN THE REAL WORLD

In 2012, 64 patients died in nine states as a result of a solution of methylprednisolone acetate (a steroid used for controlling pain) contaminated with fungus that was injected directly into the patients’ spinal cords. The contaminated injections led to complications, including fungal meningitis. The drug was manufactured by the New England Compounding Center (NECC) in Massachusetts. Another 753 patients in 20 states were seriously injured. The unclean pharmacy facilities at NECC were running without FDA approval. Mold was discovered in the “cleanroom.” A 2013 CBS 60 Minutes investigation, “Lethal Medicine Linked to Meningitis Outbreak,” uncovered the excruciating damage the surviving victims were still undergoing. It can be seen at https://PharmPractice7e.ParadigmEducation.com/LethalMedicine.

These incidents show the essential importance of sterile compounding and following precise aseptic technique and facility standards. They also show the value of the pharmacist and technician not rushing and cutting corners on sterile procedures. In December 2014, a federal jury indicted 14 NECC employees on 131 charges, including murder for two of the individuals, and also racketeering, fraud, conspiracy, and other crimes. A federal judge in 2015 approved a $200 million civil settlement for damages to victims and their families.