5.7 Parenteral Routes of Administration

A parenteral route of administration is one that uses injection to reach its destination in the bloodstream, muscle, skin, or intestine. A sterile, or microbial-free, solution (with or without medication) is administered by means of a hollow needle or catheter inserted through one or more layers of the skin.

Parenteral Dosage Forms

Parenteral dosage forms are commonly administered through four paths:

subcutaneous (subq), under the skin

intramuscular (IM), into a muscle

intravenous (IV), into a vein

intradermal (ID), into the skin

Put Down Roots

Put Down Roots

The term parenteral comes from the Greek roots para, meaning “beside,” and enteron, meaning “intestine.” Parenteral administration bypasses—or goes “beside” rather than through—the digestive tract.

Parenteral solutions—prepared for injections, especially intravenous (IV) bolus and infusions—have an immediate systemic effect, since they bypass the stomach and are rapidly absorbed and distributed into the bloodstream. The parenteral route is often used for medications whose molecules are too unstable or large to be absorbed or for medications that are broken down so quickly in the stomach or liver that they cannot be taken orally.

Because the body is primarily an aqueous, (water-containing) vehicle, the ingredients of most parenteral preparations are dissolved or reconstituted in sterile solutions, such as dextrose in water or normal saline. Even immunizations and insulin medications are premixed in solutions. Some parenteral medications are available in single-use vials or ampules that contain no preservative; others may be available in a multi-dose vial of lyophilized powder with preservatives. Preparation and administration of parenteral solutions deserve special attention because of the complexity, widespread use, and potential for both therapeutic benefit and danger. All parenteral injections—whether administered via subq, IM, IV, or ID routes—must be sterile because they introduce medication directly into the body. (This is covered more in Chapter 13.)

Name Exchange

Name Exchange

Subcutaneous injections are abbreviated as SUBCUT, Subcut, SUBC, SUBQ, SC, SQ. SC and SQ are discouraged because they get mixed up with SL.

Subcutaneous Route

The subcutaneous (subq) route of administration injects medication into the fat layer, or subcutaneous tissue, just under the skin. Common subq medications include the following:

insulin (to treat diabetes)

heparin and enoxaparin (to prevent blood clots)

sumatriptan (to treat migraines)

certain immunizations (such as measles, mumps, rubella, and others)

epinephrine/adrenaline (to treat emergency asthma attacks or allergic reactions)

Intramuscular Route

The intramuscular (IM) route of administration involves injecting the drug directly into the muscle. The IM route offers a quick, convenient way to deliver injectable medications for longer-lasting effects than some other parenteral methods. The route is used to administer several immunizations, including the influenza (flu) immunization, that are offered in many community pharmacies. IM injections are also commonly used for antibiotics, narcotics, medications for migraine headaches, male and female hormones, antipsychotic medications, vitamins, and minerals. For example, vitamin B12 and testosterone medications are commercially available as a single-dose vial and a multiple-dose vial in the community pharmacy.

Testosterone injections are available as a cypionate salt (suspended in cottonseed oil) or as an enanthate salt (suspended in sesame oil). Though not interchangeable without prescriber permission, both of these salts deliver a similar amount of medication over a 10- to 14-day period.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

Insulin is never administered intramuscularly.

The IM route is also used to deliver lifesaving medications, such as epinephrine, in an emergency. An EpiPen, a single-dose autoinjector device, delivers intramuscularly as well as subcutaneously, and it comes in different doses for adults and children. The medication device is required to be dispensed in a two-pack. It can be used for repeated injections—one can be on hand at home and the other at school. Several states allow school personnel to legally administer epinephrine in emergency situations, such as a hypersensitivity to insect stings or a severe allergic reaction to peanut butter.

IN THE REAL WORLD

IN THE REAL WORLD

Almost all insulins and insulin-like products for diabetes are administered by the subcutaneous route. Insulins vary in their onset and duration of action. Most of these medications work within 30 to 60 minutes, and some of these products may lower blood glucose levels for up to 24 hours. Insulins are also available as mixtures of rapid-acting and long-acting products, typically in a 75/25, 70/30, or 50/50 concentration. In the hospital or in the emergency room, regular or fast-acting insulin can also be administered via the IV route.

Although the response time to a medication is slower than with the IV route, the duration of action for an IM injection is much longer, making it more practical for use outside the hospital setting. In fact, some IM injections may exert a therapeutic effect for a period ranging from two weeks to three months. Still, a drawback of the IM route is its unpredictable absorption rate. For this reason, the IM route is not recommended for use on patients who are unconscious or in a shock-like state.

In an emergency situation, such as after a bee sting, an EpiPen can be administered into the muscle through clothing.

In addition to the flu immunization, the most common IM immunizations are those for tetanus, diphtheria (Td) or tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis (Tdap), meningitis, pneumonia, hepatitis A and B, and human papillomavirus. Certain drugs must be given via the IM route because they are known to irritate veins and cause phlebitis if given by the IV route. Many narcotic pain medications are administered by IM injection in the hospital and nursing home.

Intravenous Route

One of the more common parenteral routes of drug and fluid administration in hospitals and skilled nursing facilities is the IV route of administration, which means to inject directly into a vein. This allows immediate bodily access to large amounts of medicated or nutritional fluids that can be dispensed either quickly or over a longer time period. Critical care medications, antibiotics, chemotherapy, and nutrition are commonly administered in this fashion. IV medications act rapidly to control and treat symptoms and can be administered via any vein in the body.

These medications are administered using two different methods: IV bolus and IV infusion.

Both IV fluids and medications can be administered via infusions in the hospital.

IV Bolus Injections With an IV bolus injection, also referred to as IV push, the drug is administered all at once into the vein, such as in the use of epinephrine or adrenaline in the case of a cardiac arrest, or in the use of glucagon when the blood glucose level of a patient with diabetes is dangerously low. (These drugs can also be administered by the IM and subq routes.) The IV route is the preferred route of administration to deliver medications in an emergency situation.

IV Infusions An IV infusion is a method for delivering a large amount of fluid and/or a high concentration of medication directly into the bloodstream over a prolonged period and at a slow, steady rate. The ordered medications are infused into a saline or dextrose solution and hung by the bed in an IV infusion bag that uses gravity or an IV pump to gradually infuse the fluids through a tube and the needle into the vein. This method can provide a continuous amount of needed medication over a given period of time. The medication may be slowly infused over time (8 hours) in the IV solution, or it may be administered over 20 to 30 minutes in a smaller “minibag” connected to the IV solution.

The advantage of an infusion is that there is less fluctuation in drug blood levels than is experienced with other routes of administration. The infusion rate can be adjusted to provide more or less medication as the situation dictates: a higher infusion rate for pain relief or a slower infusion rate if the patient experiences side effects such as shortness of breath. If patients are dehydrated, they may receive IV solutions such as normal saline or dextrose with water (with or without added medication) to keep them hydrated.

Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is an IV infusion therapy that supplies a patient with all the nutrition and/or fluids that they need. Total parental nutrition is suited for patients whose medical conditions do not allow them to ingest anything by mouth (referred to as NPO patients, from the Latin term nil per os). They may be sustained on the nutrient-containing solutions of TPN. Olimel is an example of a TPN solution that is administered intravenously.

Intradermal Route

The intradermal (ID) route of administration is typically used for diagnostic and allergy skin testing, local anesthesia, various diagnostic tests, and immunizations. For allergy skin testing, small amounts of various allergens are administered (usually on the surface of the back or arm) to detect allergies before beginning desensitization allergy shots. For diagnostic testing, such as for tuberculosis (TB), injections are given in the upper forearm, below where IV injections are given. If a patient is allergic or has been exposed to an allergen similar to TB, the patient may experience a severe local reaction.

Put Down Roots

Put Down Roots

The word hypodermic comes from the Greek root words hypo, meaning “under or beneath,” and derma, meaning “skin.”

Administration of Parenteral Dosage Forms

All parenteral injections are administered into the body with the use of a syringe and/or needle. A syringe is a calibrated device used to accurately draw up, measure, and deliver medication to a patient through a needle. Two types of syringes are commonly used for injections: glass and plastic. Glass syringes are fairly expensive and must be carefully sterilized between uses. Some drugs may require a glass syringe due to an incompatibility with plastic material. Plastic syringes are easier to store, handle, and dispose of after use; these syringes come from their manufacturers in sterile packaging. Disposable plastic is clearly preferred medically and used both in and out of the hospital setting for most medications. For example, the blood thinner enoxaparin (Lovenox) is available in a prefilled plastic syringe in doses ranging from 30 mg per 0.3 mL to 100 mg per 1 mL. Proper disposal of plastic syringes and needles (and medications) is both a health and environmental concern. Sharps containers are recommended for home and pharmacy use to safely dispose of used syringes and needles (this will be addressed in Chapter 14 on medical safety).

Pharm Fact

Pharm Fact

The shingles vaccine must be stored in a freezer, and, once reconstituted with sterile water, the vaccine must be administered subcutaneously within 30 minutes.

Only trained professionals and healthcare providers are legally allowed to give parenteral injections. In recent years, however, home health nurses and pharmacists have taught patients (and their spouses or caregivers) how to administer injections or start infusions at home. In the pharmacy setting, many pharmacists are becoming increasingly involved in immunization administration programs after completion of training and certification, which includes cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in case of a radical immunization reaction. Pharmacy technicians, however, must check their state regulations to determine whether they are allowed to draw up or prepare injections for a final check by the pharmacist. To better assist pharmacy and hospital personnel, pharmacy technicians must have a basic understanding of various syringe and needle sizes.

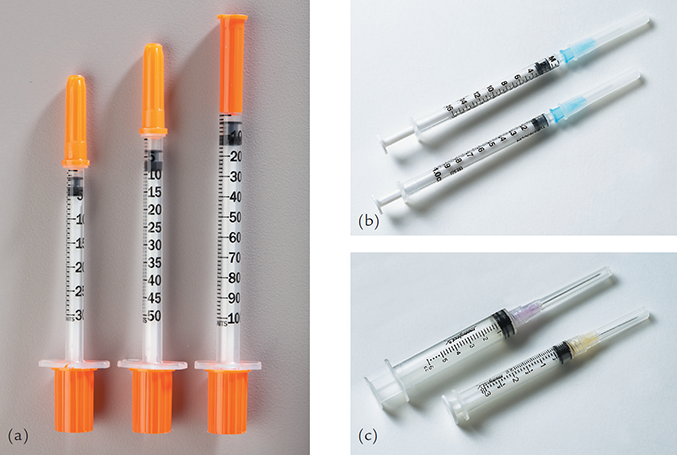

Parenteral administrations all need needles and often syringes. Common types of syringes include the following:

the insulin syringe, which measures in units, from 30 units to 100 units (equivalent to 0.3 mL to 1 mL), and has a longer needle than the tuberculin syringe; comes in sizes of 30 units or less (3/10 mL half units marked), 31 to 50 units (1/2 mL), and 51 to 100 units (1 mL)

the tuberculin syringe, with a cannula (hollow area inside the syringe needle) ranging from 0.1 mL to 1 mL

the larger hypodermic syringe, with a cannula ranging from 3 mL to 60 mL

Great care must be taken not to mix up the syringes and consequently have incorrect dosages administered. Insulin syringes are used by diabetic patients to administer insulin. Tuberculin syringes are used for skin tests and for drawing up very small volumes of solution. Hypodermic syringes are used with hypodermic needles to inject parenteral drugs into the body or to remove blood from the body (see Figure 5.5). These syringes may be glass or—more commonly—disposable plastic with clear demarcations for accurate dosing. Hypodermic syringes (without a needle) are often used to more easily administer oral liquids to infants, children, and pets.

Figure 5.5 Common Types of Syringes

(a) Insulin syringes in 30 unit, 50 unit, and 100 unit sizes

(b) Tuberculin syringes marked with metric measures

(c) Hypodermic syringes in 6 mL and 3 mL sizes

A needle is attached to the tip of a syringe to either draw fluid into the syringe or push fluid out. Needles come in various lengths and sizes. Needle length and size depend on the route of administration, patient factors such as body size, and drug formulation characteristics. Needles commonly range from 18 gauge to 32 gauge, with 32 being the thinner, finer needle. The size of the gauge corresponds conversely to the size of the needle’s lumen (hollow inner core): the larger the gauge number, the thinner the needle and the smaller the needle’s lumen.

Different states have different regulations on the sale of syringes and needles without prescriptions because of their potential diversion for the injection of illegal drugs. Some states (or pharmacies) may require a prescription or that syringes be kept behind the prescription counter to control access to their sale. Some pharmacies will not sell syringes directly to the public unless buyers can provide proof of medical necessity. The final decision may be at the discretion of the pharmacist.

IN THE REAL WORLD

IN THE REAL WORLD

Knowing and paying attention to the differences in syringe sizes can save or prevent harm to a life. In cases reported in Pennsylvania, tuberculin syringes were accidentally used to administer low-dose insulin. The tuberculin syringe, which was packaged similarly to an insulin syringe, is calibrated in milliliters (mL) from 0.1 to 1, while the insulin syringe is in units. In these cases, 0.4 mL, 0.6 mL, and 0.9 mL doses of insulin were delivered instead of the 4 units (0.04 mL), 6 units (0.06 mL), and 9 units (0.09mL) that were prescribed. So in each case, a tenfold overdose occurred—40 units, 60 units, and 90 units.

Subcutaneous Parenteral Administration

Subcutaneous injections are typically administered on the outside of the upper arm, the top of the thigh, or the lower portion of either side of the abdomen. These injections should not be made into grossly fattened, hardened, inflamed, or swollen tissue.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

Storing insulin needles separately from tuberculin needles helps to prevent confusing them.

The needle used for subcutaneous injections is typically ⅜ to ⅝ of an inch in length, with a needle gauge in the range of 25 to 32. The gauge used by patients with diabetes may vary from 28 to 32, with short, fine, or ultrafine needles. The correct length of the needle is determined by a skin pinch in the injection area. The proper needle length will be one-half the thickness of the pinch.

Safety Alert

Safety Alert

The patient or patient’s caregiver should be reminded never to touch the needle but only the cap and connecting plastic. The needle must be kept sterile.

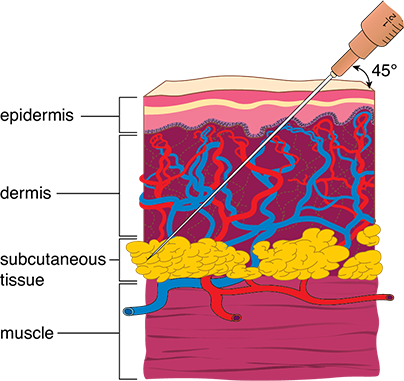

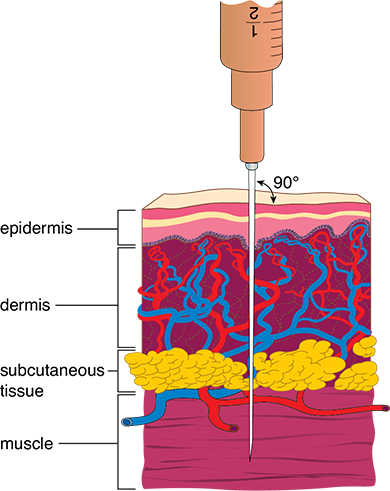

Subcutaneous injections are usually given just beneath the pinched skin with the syringe held at a 45-degree angle (see Figure 5.6). In lean older patients with less tissue and in obese patients with more tissue, the syringe should be held nearer to a 90-degree angle. To avoid pressure on sensory nerves, which may cause pain and discomfort, a volume of 1 mL or less is injected.

The medication most commonly administered subcutaneously is insulin. Insulin is typically injected several times a day, with timing generally around mealtimes and bedtime, depending on the type of insulin. Several types are available, including immediate, short-acting, intermediate-acting, and long-acting. These medications differ in onset and duration.

Disposable syringes use different sized needles, depending on the medication, the thickness of the skin, and whether it is a subq, IM, or ID administration.

Insulin absorption varies, depending on the administration site and patient activity. The patient should be properly counseled regarding the role that insulin therapy will play in meal planning and exercise so as to gain the best advantage of the medication and avoid the chances of hypoglycemia (low blood glucose levels). The pharmacist should also instruct the patient with diabetes or the parent of the patient to rotate the administration site from the abdomen, to each leg (upper thigh), and then to the arm to avoid or minimize local skin reactions and scarring.

Figure 5.6 Subcutaneous Injection

Subcutaneous injections usually are administered just below the skin at a 45-degree angle.

Syringe size, needle length, and needle gauge are critical factors in insulin product selection. A higher-gauge, smaller needle is used due to multiple daily injections. As noted, insulin dosage is prescribed in units rather than in milliliters. The concentration is usually 100 units per 1 mL. However, there is a concentrated insulin that is 500 units per 1 mL. The insulin expiration date should always be checked before administration.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

Remind patients that insulin vials should never be shaken.

Insulin Vials Insulin comes in glass multi-dose vials with rubber stoppers. The proper size insulin syringe should be selected from several volume sizes, such as 0.3 mL, 0.5 mL, and 1 mL, and is determined by the dose needed. When preparing the insulin vial for administration, the vial should be gently agitated and warmed by rolling it between the hands. Then the vial’s rubber stopper should be cleaned with an alcohol wipe before inserting the syringe.

To fill the syringe, the same amount of air as the desired insulin dose should first be drawn into the syringe and then injected into the vial through the rubber stopper at an angle. Holding the vial upright and the syringe in a 90-degree position, the correct amount of insulin should be withdrawn. To remove air bubbles from the syringe, the patient should hold the syringe needle up, tap the syringe lightly, and gently push the plunger to expel the air. If air bubbles remain, the insulin should be injected back into the container, and the process started again until the insulin in the syringe has no bubbles. Then, the injection can be performed.

Some patients require the use of two different insulins simultaneously. In order to avoid two different injections, patients may need to mix a cloudy and clear insulin from two different vials. The proper amount of air must be injected into the syringe with cloudy insulin before beginning. Because the process is complicated, the patient should always seek the assistance of a pharmacist or, if in an institutional care facility, the nurse. For more specific information on the process, see the description on the WebMD website: https://PharmPractice7e.ParadigmEducation.com/WebMD.

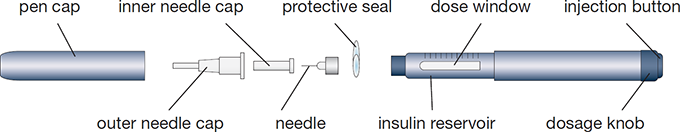

Insulin Pens An insulin pen is a portable device in which the prescribed dose of medication is “dialed up” to administer the proper amount of insulin. There are two kinds: reusable pens that use replaceable insulin cartridges, and prefilled disposable pens designed for single use. An insulin pen can deliver anywhere from 1 unit to 160 units of a prescribed insulin (see Figure 5.7). First, the patient should prime their insulin pen by dialing up two to three units (there is an audible click per dial) and shooting them in the air. Priming removes air bubbles from the pen and ensures that the pen is working appropriately. Next, the patient dials up the correct number of units and injects the medication.

Figure 5.7 Components of an Insulin Pen

The insulin pen is easy to learn, simple to use, and convenient to carry.

Insulin pens have many advantages for patients. The pens:

are more convenient and easier to transport than traditional vials and syringes

can last for nearly a month (28 days) without being refrigerated

do not require the additional purchase of syringes

deliver more accurate dosages

are easier to use for those with fine motor skill or visual impairments (such as a child or an older adult patient)

cause less injection pain (as polished and coated needles are not dulled by insertion into a vial of insulin before a second insertion into the skin)

retain a memory of past injections

are disposable

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

Some insulin therapies involve a pen for one kind of insulin and a syringe for another, or two insulin pens for two different insulin types.

The major disadvantage of the pens is their cost. Some but not all drug insurance plans cover them as they do syringes and needles. Most insulin pen companies also offer coupons. Common insulin pens include Humalog KwikPens, NovoLog, Levemir FlexPens, Apidra, Lantus Solostar, and Toujeo. Byetta and Victoza are insulin-like products that are also available in a prefilled pen.

Pharmacy personnel should be aware that insulin pens can also come in different mixes, such as the Humalog KwikPen, which is available in a 75/25 and a 50/50 mixture of immediate and long-acting insulin. Most disposable insulin devices are packaged in five-packs, with each pen or cartridge containing 300 units. For lower-dosage insulin, there are reusable pens that come in half-unit dialing increments.

Storage of Insulin All insulin must be protected from temperature extremes. Patients should be instructed to keep insulin refrigerated and to check expiration dates frequently. Opened vials or insulin pens can be stored at room temperature and should generally be discarded after one month, because the insulin can lose a portion of its potency even if stored under ideal conditions. Unopened vials or insulin pens should be refrigerated to maintain their potency until their time of expiration. If the insulin cartridges or prefilled pens have not been refrigerated for 28 days or more, they should be discarded.

Insurance Coverage for Insulin Supplies Insurance companies, including Medicare, require a prescription for coverage of syringes, needles, and other diabetic supplies, such as lancets, blood glucose monitors, and test strips. For patients over age 65, Medicare may cover some of the cost of diabetic supplies if proper paperwork is completed. Assisting patients with diabetes is a very important role for the pharmacy technician in the community pharmacy.

Safety Alert

Safety Alert

In the past, insulin pens all contained standard concentration insulin (100 units per 1 mL). Now insulin pens are also available with concentrated insulin (300 units per 1 mL).

Intramuscular Parenteral Administration

In adults, IM injections are generally given into the muscular portion of the upper or the outer portion of the gluteus maximus (the large muscle of the buttocks). Another common site, especially for immunizations, is the lower portion of the deltoid muscles (at the top of the shoulders). Care must be taken during deep IM injections to avoid hitting a vein, artery, nerve, or even bone. Figure 5.8 shows the needle angle and injection depth for an IM injection. The volume of IM injections is usually limited to less than 2 mL.

Some diabetes patients use a subcutaneous injection.

Figure 5.8 Intramuscular Injection

Intramuscular (IM) injections are administered at a 90-degree angle.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

Remember: the larger the needle’s gauge number, the smaller the lumen and the smaller the hole the needle makes. Conversely, the smaller the gauge, the larger the lumen and the larger the hole.

IM injections typically are administered using a 22- to 25-gauge, ⅝ to 1.0 inch long needle. The needle must be sufficiently long to inject the drug through the dermal or skin layers into the muscle. The needle length for an IM injection may also be dependent on the patient’s fat content versus lean muscle at the injection site. A smaller-size needle can be used in a lean patient with average or smaller arm size or skin thickness. Though a large gauge (smaller needle) is always preferable for patient comfort, some medications, due to their viscosity (such as hormone injections), may require a small gauge (thicker needle) to withdraw the medication from the vial and inject the drug into the muscle.

As explained earlier, some emergency medications, such as epinephrine, are administered intramuscularly by EpiPens or other specialized devices. The Twinject auto-injector is a device designed to administer a first dose of epinephrine in an emergency into the thigh muscle through clothing. The auto-injector must be held against the skin for 10 seconds for the medication to be released. A second dose may be administered into the muscle if needed. An IM injection does not work as fast as an IV injection (or infusion), but the pharmacological effect will last longer.

Intravenous Parenteral Administration

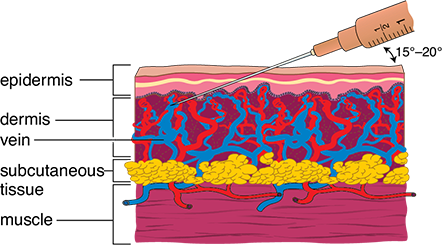

IV bolus injections and infusions are usually administered into visible major veins, most often the vein of the arm inside the elbow although other sites are used as well. These injections are given at a 15- to 20-degree angle (see Figure 5.9).

Figure 5.9 Intravenous Injection

Intravenous (IV) injections are administered at a 15- to 20-degree angle.

Before administration of the IV solution, the nurse must inspect the solution for precipitates, swab the IV site with an alcohol wipe, and select the correct syringe and needle for the procedure. During administration of the IV product, the nurse must ensure that the solution is free of particulate matter and air bubbles—both of which may lead to embolism (blockage of a vessel) or phlebitis (a severe painful reaction at the injection site).

The IV route does have associated inherent dangers. A major disadvantage is the potential for introducing toxic agents, microbes, or pyrogens (fever-producing by-products of microbial metabolism) straight into the vein, resulting in their dispersal throughout the body. Consequently, to minimize infection, IV products are prepared by pharmacy technicians in an isolated cleanroom environment using special techniques and equipment to ensure sterility, which will be explained in depth in Chapters 12 and 13. After preparation of each IV product, the technician as well as a pharmacist must inspect the solution for contaminants as well as salt precipitates, which are evidence of incompatibility.

Failure to follow protocol for IV products may result in serious adverse effects for the patient. (To learn more about germ theory and the importance of aseptic technique, see Chapter 12.)

Infusion pumps are primarily used in the inpatient hospital setting to deliver IV infusions. They continuously deliver medication 24/7 to regulate the amount, rate, and/or timing of infused fluid or medication. Examples of infusion pumps include the following:

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

Pharmacy personnel should be aware that PCA pumps are patient-controlled. Patients push a handheld controller to self-administer a dose of pain medication intravenously.

a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump, which is a programmable machine that delivers small doses of painkillers on patient demand

a jet injector, such as for epinephrine, which uses pressure rather than a needle to deliver the medication in an emergency

an ambulatory injection device, such as an insulin pump, that the patient can wear while moving about and maintaining a normal lifestyle

Infusion pumps are commonly used in the hospital to accurately regulate the rate of IV infusions.

Because infusion pumps are electronic, they need to be tested between patients to make sure that they are working properly and infusing accurately.

Intradermal Parenteral Administration

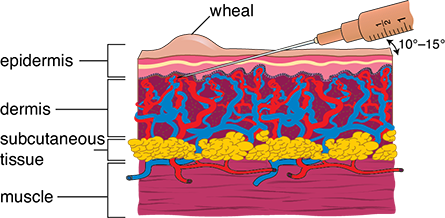

ID injections are given into the capillary-rich skin layer just below the epidermis (see Figure 5.10). A small amount of medication is injected into the dermal layer of skin to form a wheal, or small raised reddened mark. It is used for allergy and TB tests.

Figure 5.10 Intradermal Injection

Intradermal injections pierce the skin at a 10- to 15-degree angle. A small amount of medication (0.1 mL) is injected slowly into the dermal layer to form a wheal.