11.4 Filling and Delivery of Medication Orders

Prior to the electronically tracked administration, the medication order must be properly filled in the pharmacy. The software reconciles the medication orders with the patient’s diagnosis and treatment and guidelines from the software’s database of medical and pharmacy literature on “best practices,” such as clinical guidelines, hospital protocols, and dosing guidelines for different patient populations.

The pharmacy technician receives the printout of the medication order list to begin the process of filling it.

As in community pharmacy prescriptions, the software also reconciles the medication order with the patient’s personal medication history, allergies, and other drugs being administered. The program looks for duplicate drugs, incorrect doses, and laboratory test results that may have an impact on the choice of drug or dose.

Pharm Fact

Pharm Fact

When technicians are handling patient information and working with EHRs, they must follow strict hospital protocols to protect patient privacy per federal HIPAA law.

For pharmacists, the EHR system provides easy access to clinical information contained in the patient medical record and provides better medication therapy management. If an issue is flagged by the medical software, the order will not be filled until the pharmacist can review it, or the physician is notified and the issue resolved.

After the medication order has been checked and verified by the pharmacist, a medication label is generated, and the order can then be filled by the pharmacy technician (or the robot) using bar codes, verified again by the pharmacist, and sent to the patient care unit for administration by the nurse.

Medication orders in a hospital are dispensed to patients through one of the following distribution systems: dispensing carts (unit dose and emergency carts), robotic filling and dispensing, automated floor stock, or an IV admixture service. Pharmacy technicians are actively involved in all of these pharmacy methods of delivery to the nurses for administration.

The Unit Drug Packaging System

Unlike a 30-day or 90-day supply of medication dispensed in the community pharmacy, technicians in a hospital pharmacy typically prepare enough single-unit medications for only 24 to 72 hours (depending on the size and scope of the hospital pharmacy). A unit dose is a drug amount prepackaged for a single administration. Most common oral medications—such as tablets, capsules, and some liquids—are commercially available in a unit dose formulation.

With prepackaged individual dose units, the manufacturer puts a bar code on the label for scanning and an expiration date and lot number for tracking in case of a drug recall.

Costs and Benefits of the Unit Dose System

The cost of one dose of medication is proportionately higher in a hospital than one dose from a retail pharmacy. That is because this cost usually includes a portion of the staff time of the pharmacy and nursing personnel and the other hospital overhead as well as the unit dose packaging. Consequently, a dose of Tylenol in the hospital may cost $5 or more per tablet.

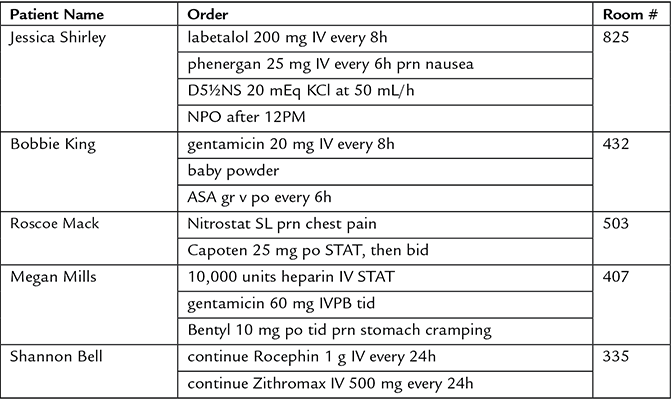

Bar code scanning and automation technologies help reduce errors by ensuring the right drug and dose are delivered to the right patient.

However, traditionally the unit dose drug distribution system has offered several benefits for patients, healthcare personnel, and hospitals that offset the higher packaging costs and more labor-intensive activity involved in utilizing this system:

Streamlined Work Flow Process With the drug formulation already prepared, packaged, and labeled, nurses on the patient care unit can administer the medication to the patient more efficiently, thus saving nursing staff time for other patient care responsibilities.

Decreased Medication Errors The bar code on the unit dose package label offers another medication safety check. If a medication does not scan correctly to match the patient’s wristband (BPOC), then the wrong medication (or wrong dose) has been sent, and the error is detected before patient administration.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

Only unopened unit doses can be returned to stock. For ease of reuse, the unit doses are labeled with the name of the drug, its strength, and the expiration date.

Increased Medication Security A unit dose system is locked at all times for added security when not in use by the nurse administering medications. The administration of each dose for each patient must be documented by the initials of the nurse in the eMAR.

Reduced Medication Waste In the unit dose system, unused medication whose packaging has not been compromised and bears a valid expiration date can be returned to inventory in the original, unopened package and reissued.

Increased Cost-Effectiveness for Hospital and Patient A unit dose system provides an easier method for the hospital accounting department to maintain patients’ accounts (including charges and credits), as each medication dose that is administered is billed to the patient’s account.

A unit dose cart has individually labeled drawers that contain medications for patients assigned to a room in a designated nursing area.

Design of the Unit Dose Delivery Cart

The unit doses are delivered with a mobile cart—a small rolling cabinet that contains a number of small removable cassette drawers. There are different kinds, such as the daily dose unit cart, which gets delivered on a regular schedule to the nursing units, and the emergency crash cart, which holds all the most needed crisis drugs for ready use. The hospital pharmacy is responsible for stocking as many unit dose carts as there are nursing units, plus the emergency crash carts, drug boxes, and any other mobile carts.

In a unit dose cart, each drawer houses the daily medications for a specific patient on the nursing unit. Typically, the cart has two sets of drawers: one set for delivery to the patient care unit and a replacement to be filled by the pharmacy while the cart is on the nursing unit. These drawers are filled and maintained by the pharmacy technicians. Each cassette drawer is labeled with the patient’s name and room number until discharge from the hospital or transfer to another care unit. Each drawer contains a sufficient quantity of the patient’s medications for a 24- to 72-hour span (per hospital policy), though smaller hospitals may exchange patient drawers less frequently. The drawers in the unit dose carts are typically exchanged after the scheduled morning dose administrations and then returned to the nursing station to be locked for security until the next administration time later in the day.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

Necessary medical supplies such as insulin vials and pens, inhalers, and other multiple-use items have to be delivered to the patients and charged to their accounts.

Filling the Daily Unit Dose Cart

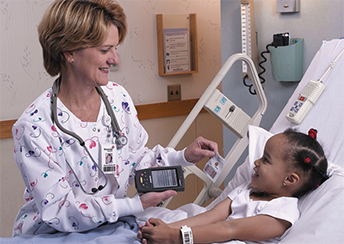

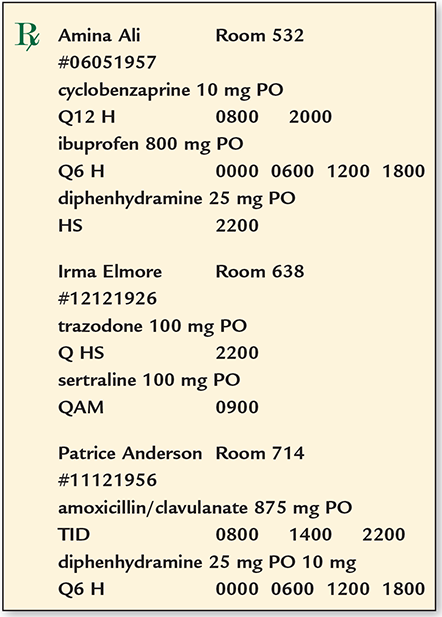

The pharmacy software collates the medication orders of every patient in a nursing unit to generate a complete medication order list, or cart fill list. Each morning, it is printed out by the pharmacy technician (see Figure 11.3) prior to cart filling.

More than one technician is commonly involved in cart filling at the same time. Pick stations, as they are called, store frequently used unit dose medications arranged in small, stacked storage bins that are readily available. Each technician has a designated pick station for cart filling. Multiple pick stations in a larger hospital pharmacy allow more efficient patient drawer filling for more technicians.

Figure 11.3 Cart Fill List

As a technician, you will read the list description of each medication order and its signa codes to determine the type and number of unit doses required for the patient’s dosage schedule (see Figure 11.4). For example, if a prescriber orders Zofran 4 mg po every six hours prn, this translates to 4 milligrams of Zofran, in oral form, to be taken every six hours as needed. With these signa code directions, or sigs, a maximum of four doses is designated for any 24-hour period. If the unit dose cart is exchanged every 72 hours, then 12 doses of Zofran would be needed.

Each hospital has a standard schedule for dose administrations in regular staggered hours, such as every 4, 6, 8, or 12 hours. For example, if a patient is prescribed penicillin VK 500 mg po every six hours, the doses should be administered at 0600, 1200, 1800, and 0000 according to the military (24-hour) clock. These times would be 6 a.m., noon, 6 p.m., and midnight. (For more on the conversion from the 12-hour to 24-hour clock, see Chapter 6.)

As with the community pharmacy, it is important to memorize the sigs. For common dosage sigs for scheduled dosages, see Table 11.3. The “q”s for “every” are crossed out in many of the acronyms to indicate that they should no longer be in use in US hospitals because the Joint Commission (JC) and the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) have put them on their lists of “Do Not Use” or “Error Prone” abbreviations. In many cases, the word “every” should be fully written out, but you may see the q still used. (For additional common sigs, see the Common Prescription Abbreviations Table in Chapter 7.)

Table 11.3 Hospital Dosage Timing Signa Codes

Acronym |

Timing of Dosage |

|---|---|

q |

every |

h |

every hour |

am |

every morning |

pm |

every evening |

hs |

every night at bedtime |

d |

every day |

od |

every other day |

wk |

every week |

q__h |

every [#] hours |

bid |

twice a day |

tid |

3 times a day |

qid |

4 times a day |

x_d |

times [#] days |

prn |

as needed |

After you select each medication out of the pick station, select the correct dose, dosage form, and amount of unit doses needed. The quantity of unit doses to place in the drawer will depend on the dosing frequency and the hospital policy on frequency of unit dose cart exchanges (i.e., every 12, 24, or 72 hours or once weekly). Each unit dose product label includes the following information:

Each of these two pick stations, red and blue, contains the common oral unit doses that are needed to fill the individual drawers of a unit dose cart.

generic or brand name of the drug

dosage and special instructions

strength of the drug

manufacturer’s name, lot number, and expiration date

bar code of the product

Safety Alert

Safety Alert

Remember that po means orally or “by the mouth” whereas npo indicates that nothing should be given orally, so infusions, patches, suppositories, or other means of delivery will be needed.

Verify the information to make sure that it matches the cart list and what you collected. Place the medication in the unit dose drawer that is labeled with the patient name and room number. If the patient is receiving other medications, add those unit doses to the same drawer. Before delivery, the pharmacist in charge must do a final check. (If there is a tech-check-tech supervisor, this check would occur before the pharmacist’s final approval.)

.png)

Commercially available unit dose labels contain the drug, dose, and bar code.

Unlike formulary drugs, Schedule II, III, and IV substances are not dispensed in a unit dose cart per hospital policy. Instead, they are obtained from the locked, secure automated medication delivery system on each nursing floor, where the administration of each dose for each patient is documented by the nurse, which will be addressed later in this chapter. This restriction and security minimize illegal drug diversion.

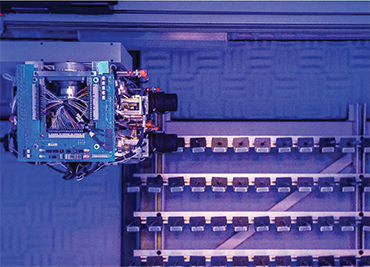

Robotic Filling

Many medium- to large-size hospital pharmacies now use a centralized, automated robotic dispensing system to more efficiently and accurately fill unit dose orders. This automated medication filling and dispensing system, which is housed in the pharmacy department, is also integrated with hospital and pharmacy software. Larger models can store more than 1,000 (or 90%) of the most frequently prescribed medications, and, in some systems, they may even send the dosages directly to the nursing floors through pneumatic tubes. Similar to a vending machine, this type of dispensing system can hold most of a hospital’s drug inventory of selected drugs for three days and can accommodate most dosage forms—tablets, capsules, prepackaged unit dose liquids, patches—even those items requiring refrigeration. It does not handle cleanroom IV infusions and injections.

Figure 11.4 Medication Order Printout

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

Some hospital pharmacies have a technician supervisor check (tech-check-tech) the steps in a prepared medication order prior to the pharmacist as an added safety verification step.

For security reasons, there are no controlled substances stored in the robot. Robotic dispensing is sometimes done offsite due to space requirements, and the facility that houses this technology is often centrally located to serve several area corporate hospitals, much like a mail-order warehouse.

This ROBOT-Rx was installed in 2015 in the new Montreal Children’s Hospital.

Photo courtesy of the Montreal Gazette.

Operation of the Robot

After a medication order is digitally entered into the system and checked by the pharmacist, the robot takes over. Using bar code technology, the robot can pick, count, package, label, store, and dispense the unit dose medication. (The automated robotic dispensing system can also be used to repackage a high volume of drugs if needed and programmed to do so.) The robotic arm uses suction and pneumatic tubes to pull the correct bar-coded medication and transfer it to a collection area, where it is packaged into an envelope or dispensed onto a tray for the technician to insert into the proper drawer of a unit dose cart or dispensed directly to the nursing floor. In addition, the robot can process drug returns, credits, inventory reordering, and record keeping. A designated technician has the responsibility of restocking the robot’s pick station with replacement inventory.

To utilize a robotic system, a hospital or warehouse pharmacy has to process a high-enough volume of medications to justify the cost and the amount of space it takes up.

Benefits of Robotic Filling and Dispensing Systems

There are many advantages to using automation for dispensing medications in the hospital setting, including the following:

Decreased Medication Errors For instance, when used in combination with CPOE and BPOC technologies, ROBOT-Rx (Omnicell) automation has resulted in an accuracy rate of 99.9%. The human rate is about 97.2% with an error rate of 2.8% (according to the company’s statistics). One-third of medium- and large-size hospital pharmacies currently use ROBOT-Rx automation for medication dispensing, and half of these hospitals have also adopted BPOC technology.

Reduced Pharmacy Workload Dispensing requires more than 10 discrete steps from physician order entry to nurse administration of the drug at the patient’s bedside. Robotic dispensing has been estimated to reduce the workload of pharmacists by 90% and the workload of pharmacy technicians by 72%, allowing them to redirect their energy to other needed areas.

Increased Long-Term Cost Savings The high short-term costs associated with purchasing and installing the robotic dispensing system (which amount to approximately $750,000 to $1 million) are substantial. For smaller hospitals, these costs are prohibitive. Cost savings may be realized in staff efficiencies, improved productivity, and fewer medication errors, resulting in fewer litigation and settlement costs. As costs decrease in the future, such automation will likely become the standard of care within the hospital pharmacy community.

Pharmacy technicians are responsible for filling the daily unit dose carts with packaged medications for each patient’s individual drawer.

Processing the Returned Unit Dose Cart

When the unit dose cart is returned to the pharmacy, the pharmacy technician empties all patient cassette drawers and reconciles any returned medications. Unit dose medications may not have been administered for a variety of reasons. The patient may have been undergoing a procedure such as an x-ray at the scheduled medication time; or was told not to take oral medications before surgery per physician’s order (NPO, or nothing by mouth); or may have become nauseated so that an oral medication was changed to an injectable or a suppository dosage form. These notes are commonly recorded in the EHR.

Though the dose may have been intentionally skipped, it may also have been missed accidentally and not administered. Some pharmacy departments use the medications remaining as a quality assurance tool—they may prompt an investigation into why a medication was missed. The pharmacy technician plays a crucial role in bringing missed doses of drugs, such as antibiotics, or a pattern of several missed doses to the pharmacist’s attention. The technician may be asked to visit the nursing unit and conduct an investigation as to why the medication dose was not administered to the patient.

Labeling and Documentation of Repackaged Unit Dose Medications

Not all drugs are commercially available in unit dose packaging, so the pharmacy technician often needs to repackage medications from bulk containers into unit doses and give them a bar-coded label. A medication special is a single dose preparation that is repackaged for a particular patient and checked by the pharmacist. The process of creating patient-specific unit doses from stock drugs is labor intensive and often the responsibility of a designated pharmacy technician.

To hand package solid oral medications in unit doses, you will generally use heat-sealed bags, adhesive-sealed bottles, blister packs, and heat-sealed strip packages. For oral liquids, you will measure the medication into plastic or glass cups, heat-sealable aluminum cups, and plastic syringes labeled “For Oral Use Only.” Whatever packaging is used, it needs to provide an airtight and light-resistant delivery system to ensure the drug’s physical stability.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

Expiration dates and lot numbers must be included on all repackaged medications. When a drug is repackaged, the expiration date changes from the stock expiration date.

All repackaged unit doses are placed in an envelope or a plastic bag and labeled with the patient’s name, the drug name and dose, the medication administration time, lot number, expiration date, and an identifying bar code. As a final check, scan the bar code of the computer-generated unit dose label and/or envelope before the medication order is placed in the unit dose drawer.

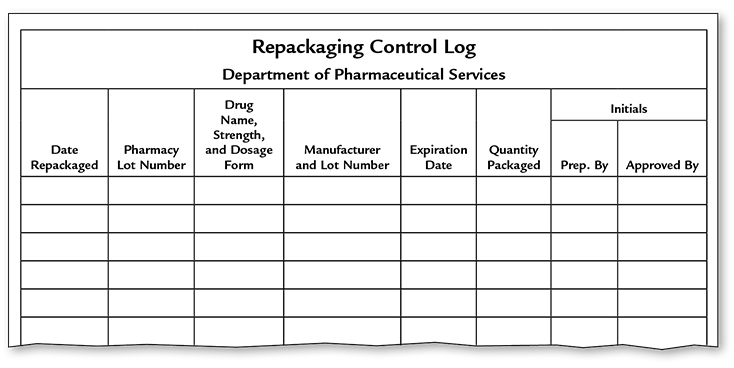

After repackaging, you must legally document the essential information about the repackaged medications in a digital repackaging control log (or handwritten repackaging logbook, though this is now less common). (See Figure 11.5.) This information must include your initials as the repackaging technician as well as the initials of the pharmacist who checked the medication.

Any home meds that are to be delivered in the daily dose carts also need to be repackaged as unit doses, affixed with a bar-coded label, and portioned out in correct scheduled doses for the cart fill. At discharge, any remaining stock of the home meds will be returned to the patient.

Figure 11.5 Repackaging Control Log Information

This information must be entered and filed in the computer or logbook to document and track repackaging.

Large hospital pharmacies use a variety of time- and cost-saving devices to assist technicians in medication preparation and repackaging, such as automated pill counting machines and high-speed packaging and dispensing machines for oral medications (for example, PACMED by McKesson). Such automation can improve efficiency by reducing cart fill times, lowering inventory costs, and improving patient safety. Such automation can also interface with robotic systems, which will be explained, to produce additional efficiencies and safety in hospital pharmacy operations.

Processing Missing Orders

If an order is received in the pharmacy department after the unit dose cart has already been delivered to the nursing floor, an individual medical order will have to be filled and delivered to the nursing unit. You will need to calculate the sufficient amount of the unit dosage needed for the patient until the next cart exchange (and have it checked by the pharmacist). For example, if an order is received at 1300 (1 p.m.) for Zyrtec 300 mg every 8 h (0600, 1400, 2200) and the next cart exchange is at 0800 (8 a.m.) the next morning, then three doses need to be delivered for the administrations at 1400 (2 p.m.), 2200 (10 p.m.) and 0600 (6 a.m.).

Put Down Roots

Put Down Roots

Code blue is thought to have come from a code of procedures to assist someone turning blue from lack of oxygen.

Stocking Emergency Drug Crash Cart and Drug Box

Another significant drug cart that technicians are responsible for stocking is the crash cart—a mobile cart that holds necessary drugs for an emergency code, such as a code blue calling for immediate resuscitation of a patient in respiratory failure or cardiac arrest. The pharmacist verifies the select drugs necessary for restocking the depleted cart, and the technician fills the crash cart with these drugs and checks the expiration dates of all the remaining medications to replace them if they are near expiring. The technician then presents the cart to the pharmacist for review and verification. This cart (or carts) may be housed in the pharmacy, on a nursing unit, or in the emergency department. Pharmacy technicians may also be responsible for restocking the paramedics’ emergency drug box after an ambulance run. The crash cart or emergency drug box is sealed after the pharmacist’s final check until it is needed.

The pharmacy technician checks missing stock and expiration dates to restock the emergency drugs for the hospital crash cart.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

Technicians are responsible for finding out which patient received a crash cart medication to have that patient’s account billed.

Safety Alert

Safety Alert

Robotic and automated dispensing equipment is only as safe and accurate as the pharmacy technicians who fill it, the pharmacists who verify the fills, and the nurses who administer the medications.

Stocking Floor Stock Automated Dispensing Cabinets

Not all medications are delivered through unit dose carts. Floor stock is a secured inventory of frequently prescribed drugs and IV solutions that are stored on the patient care unit. Historically, floor stock was limited to commonly selected drugs used on a prn, or as needed, basis and it included mainly over-the-counter medications. Ointments, creams, antacids, ear drops, and eye drops—considered bulk items—were all commonly supplied as floor stock and placed at the patient’s bedside upon a physician’s order.

Almost all US hospitals now place floor stock (plus other commonly used Rx medications) in a high-technology automated dispensing cabinet (ADC). An ADC is a mechanized locked cabinet with several drawers for medications, which is specifically designed for each nursing unit to dispense unit doses, similar to a vending machine. Some drawers of the cabinet may be refrigerated; other drawers contain oral and injectable narcotics with a higher level of security and documentation required. These cabinets work with automated medication dispensing system (AMDS) software that is integrated into the hospital’s patient management system to increase efficiency, safety, and security.

This automated delivery system dispenses stock drug items to the nurse on the patient care unit.

The pharmacist must initially approve all new medication orders that are to be filled in the ADC. The nurse then logs onto the computer located on the dispensing cabinet and uses touch screen technology to match a patient’s specific medication order with the floor stock stored in the ADC. The AMDS software highlights the status of each medication order, indicates the exact location of the prescribed medication in the storage cabinet, and then records the time and initials of the nurse who retrieves and administers the medication. (There is a specific labeled compartment for each medication in the ADC.) Each dose of each drug is documented in the AMDS and registers on the computerized screen. The drug bar codes from the ADC and the patient wristband are scanned for a match before each drug administration.

Integrating automated robots, AMDS, CPOE, BPOC, and eMAR has reduced many types of hospital medication errors.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

Bar code scanning of each drug before restocking it in the automated dispensing machine reduces restocking and potential medication errors.

Automated Dispensing Cabinets Restocking

A technician is responsible for restocking the ADCs on different floors with common medications on those units. The AMDS provides automated reorders of inventory levels to be sent to the pharmacy. For each drug in the ADC on each nursing unit, the PAR level, or the minimum stock level to spur a reorder (with the maximum reorder amount), is set by the pharmacy department. (PAR stands for periodic automatic replenishment). These automated systems optimize inventory control by minimizing costs and out-of-stock items.

Throughout the day, the nursing units also send reports, sometimes called “out-of-stock reports,” to the hospital pharmacy requesting that selected drug inventory be replaced. Before a technician refills the automated dispensing cabinet, a pharmacist checks all of the medications to be sent up to the floor by request or procedure. Double-checking as you fill the cabinet or the robotic dispensing unit shelves is essential. If a technician absentmindedly places Fiorinal where Fioricet should be, the wrong medication could be dispensed. That is why you need to scan the bar code of the drug and label before restocking the ADCs (or a robot in the central pharmacy). This scanning will prevent a restocking error. You also need to check all the medication expiration dates and adjust inventory levels as needed.

IN THE REAL WORLD

IN THE REAL WORLD

One technician recalls, “There have been several medication errors that I have encountered while filling medications in the Pyxis machine. I was filling the Bupropion XL spot when I found that another technician had filled it with Bupropion SR instead, and the pharmacist had verified it.” Other errors she caught were hydroxyzine filled instead of hydralazine and Plavix instead of Paxil. “As pharmacy technicians,” she added, “we always have to be the second eye of the pharmacist and always double-check all of the medications even if the pharmacist has verified them.”

Since ADCs are locked, narcotics are now commonly included in the floor stock inventory of each patient care unit in the hospital, though type and quantity will vary by unit. Depending on hospital policy, the exchange of narcotics from the pharmacy technician (or the pharmacist) to the floor ADC and a nursing staff member requires documentation, including the names of both parties, the name and quantity of each dose of narcotics being delivered, and the date and time of delivery. A careful audit trail must exist from the manufacturer to the pharmacy to the patient in order to account for each dose of each Schedule II drug to comply with strict regulations established by the DEA.

Though medications are stored on the nursing units, the Joint Commission holds the pharmacy department accountable for monitoring the safety, security, and inventory of the AMDS.

Automated Dispensing Cabinet and Automated Medication Dispensing System Advantages

The nursing floor ADC run by the AMDS offers several advantages for patients, healthcare personnel, and the hospital. These benefits offset the high equipment cost that is initially involved in implementing this type of drug distribution system. The use of AMDS reduces the incidence of medication errors. In one study, the Pyxis AMDS reduced medication errors by 82%. This streamlined process also saved time and allowed nursing personnel to administer medications in a timelier manner and spend more time providing patient care. With nursing floor ADCs, pharmacy technicians can spend more time on refilling, repackaging, and sterile compounding duties. By having the most frequently needed medications on each nursing unit, there are fewer telephone calls and interruptions of daily activities in the central pharmacy.

Practice Tip

Practice Tip

Each hospital has its own mix of automated equipment and storage/dispensing units that technicians must know how to fill and run.

The ADCs offer great security advantages too because they can be set up for various security levels, such as prn medications, frequently used drugs, and controlled substances. The system can be programmed with different security and process parameters set for pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, nurses, and nursing supervisors. The AMDS documents each step of the medication dispensing and administration process, tracking all medications by type of drug, dose, patient, and caregiver. It also captures all charges for dispensed medications. The security and accountability incorporated in the AMDS provides a strong deterrent to illegal drug diversion and medication theft of controlled substances.

Robotic dispensing and automated cabinets are just the beginnings of the automated solutions. There are large and small varieties of automated storage and filling units (including specialized narcotic stations), carousels, packaging, and bar code labeling equipment. As a technician, you will have to learn well the specific handling of all automated equipment.

Cleanroom Services

Many medication orders that cannot be filled in unit dose carts or general floor stock must be individually prepared in sterile controlled environments with aseptic technique for administration into the patients’ veins through IVs and injections. These drugs include, among many different kinds, infection-fighting antibiotics, hazardous drugs, and total parenteral nutrition (TPN), also known as intravenous feeding. TPN is a specially formulated IV solution that provides for the entire nutritional needs of a patient who cannot or will not eat solid food. It may contain more than 20 ingredients, including amino acids, carbohydrates, fats, sugars, vitamins, electrolytes, and minerals. Recipients of TPN include patients of all ages, among them premature infants and newborns. A TPN service team usually is composed of a physician, a nurse, a nutritionist, and a pharmacist—all of whom have specialty training and/or certifications. This team sees all TPN patients each day, writes medication orders, and monitors patient progress.

Unlike other parenteral medications, TPN is usually administered directly into a large vein (often the vena cava), so it is extremely important that the solution be sterile. The solution may be hanging at room temperature for up to 24 hours or longer, and it is essential that it be contaminant free so that nothing microbial grows within that time.

Preparing TPN and all parenteral sterile solutions is called an intravenous (IV) admixture service or infusion service (also known as an IV additive service). Technicians in the general hospital pharmacy are not preparing or handling these solutions, as this is left to the specially trained technicians and pharmacists in the hospital cleanroom and hazardous compounding areas (the processes of which will be described in more depth in Chapters 12 and 13). However, certain common infusions and injection solutions can be made by automated sterile compounding systems, such as RIVA (Robotic IV Automation) and Intellifill IV. These are installed in the hospital cleanrooms to help the technicians compound more parenteral products.

Smaller hospitals may elect to outsource their TPN preparations to a larger hospital pharmacy or an offsite infusion pharmacy. In this situation, the physician order for TPN is received by the hospital pharmacy, reviewed and verified by the hospital pharmacist, and then forwarded to the outsourced pharmacy. The offsite pharmacy is then responsible for the preparation, expiration dating, verification, labeling, and transport of the final product to the hospital. The director of the hospital pharmacy must be assured that the offsite pharmacy meets all state and federal laws and regulations as well as adhering to the standards set by the USP and the Joint Commission (which will be described in greater detail later on).