CHAPTER 9 • LESSON 14 • INVESTIGATE

How should we evaluate trade-offs when considering different solutions?

PURPOSE | To figure out science ideas that help us toward answering our Driving Question by gathering and making sense of evidence.

TIME

Two 50-minute class periods

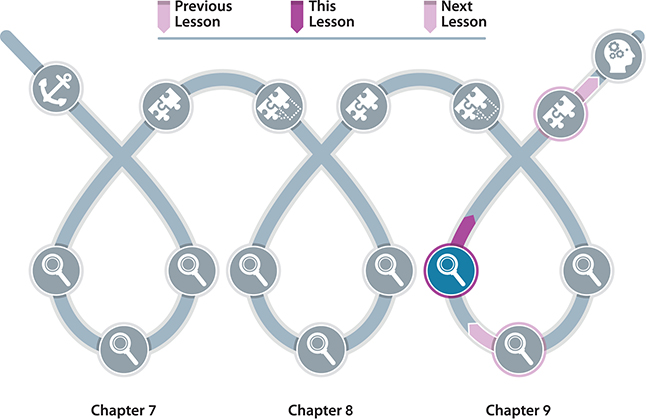

PREVIOUS LESSON | We figured out that individuals and communities can intervene in different ways and at different scales in the ways they produce, access, and consume food to improve food systems. This left us wondering how and why individuals and communities prioritize different criteria over others when making their decisions.

THIS LESSON | We figure out that the design of a food system requires consideration of several criteria including nutritional, resource use, and social implications, and decisions to prioritize certain criteria over others may be needed. We also figure out that local solutions need to account for local ecological resources and constraints. This leaves us wondering what we need to understand and consider to design an improved food system.

NEXT LESSON | We will figure out that understanding how our bodies use food for matter and energy, how different types of organisms we eat obtain their matter and energy, and how human societies balance nutritional, environmental, and social impacts provide a basis for developing an improved food system. This will leave us wondering how we can develop and evaluate our design to improve one aspect of a local food system.

LESSON LEARNING GOAL

LESSON LEARNING GOAL

Evaluate solutions based on scientific and social understandings of ways to improve food systems while considering trade-offs of different solutions.

Lesson question

How should we evaluate trade-offs when considering different solutions?

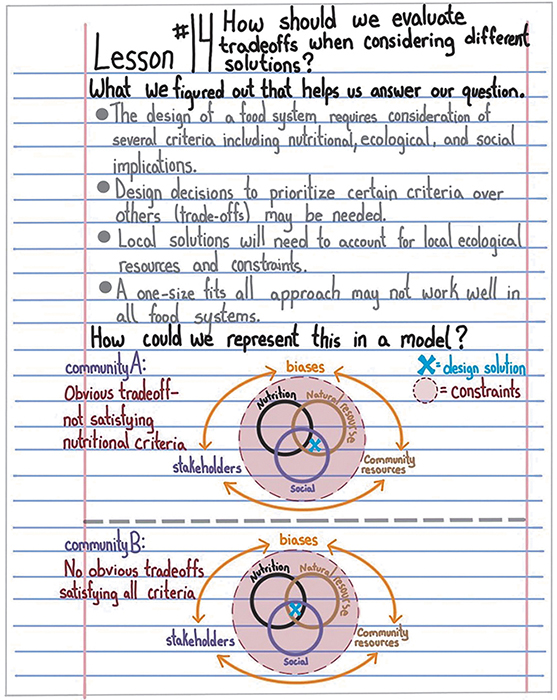

What students figure out

The design of a food system requires consideration of several criteria including nutritional, ecological, and social implications.

Design decisions to prioritize certain criteria over others (trade-offs) may be needed.

Local solutions will need to account for local ecological resources and constraints.

A one-size-fits-all approach may not work well in all food systems.

What we are not expecting

Where we are not going yet

We are not yet asking students to design solutions that improve their local food system.

Boundaries

We do not expect students to memorize the details of any of the case studies presented.

Relevant common student ideas

There is always a right solution. (Every solution has trade-offs. Engineers evaluate the range of effectiveness a design solution has in meeting its criteria.)

Everyone should be a vegan to immediately make the most positive changes to our health and the environment. (Food choices at all scales have trade-offs. One specific diet will not necessarily meet every individual’s needs well. Multiple solutions at varying scales working in concert are more likely to be successful for impacting change.)

A solution will always benefit everyone. (There are consequences that affect both those who make a decision and those who were not a part of the decision-making process. Oftentimes consequences disportionately affect people who were not a part of the decision-making process.)

Global issues can’t be affected by individuals or small communities. (Solutions that occur locally or during a short time can have long-term and large-scale effects.)

Key literacy and sensemaking strategies

Reading Strategy: Student Choice

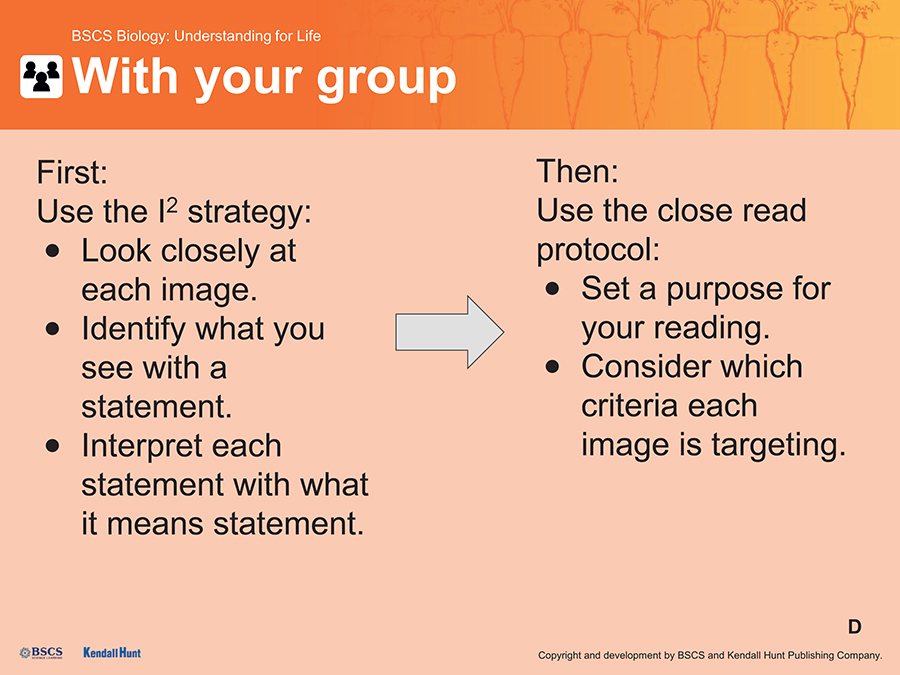

Students may choose to use the Reading Annotation Stems for reading texts and interpreting images. At this point, students should be familiar with using strategies such as the Science Close Reading Protocol and the I2 strategy to assist them with these tasks. Look for students to reach for these strategies as needed.

Communicating in Scientific Ways

To aid them with these discussion-based activities, students will also rely on the Communicating in Scientific Ways talk stems.

Word Wall

Students earn the words trade-off and constraint.

Model Tracker

Students will use their Model Trackers as they express ideas they have figured out and sketch a model to show them.

Model Tracker Self-Assessment and Feedback Tool

Students use this tool to assess their Model Tracker.

Model Tracker Formative Assessment Tool (teacher-only)

Teachers use this tool to observe and provide feedback on student progress.

ASSESSMENT

Formative Assessment: I2 Annotations

Student thinking can be revealed in what they chose to note in their I2 statements as well as what they write about the justification for their label choices and the design solutions.

Reading students’ identify and interpret statements on the images is a good way to assess how well your students understand the I2 strategy, as well as their proficiency for using what they see and their scientific knowledge about nutrition as evidence for making statements about what the image is trying to convey to consumers.

Formative Assessment: Model Tracker

After completing this lesson and before the next (Synthesize) lesson, use the progress tracker tool to assess individual student progress across this chapter and whole-class readiness for the Synthesize Lesson.

Examine the Model Tracker entries for Lessons 12, 13, and 14 in student notebooks. Provide feedback to students regarding the models for these lessons. Give students feedback on:

Any missing, or extraneous components.

Whether or not they have used the model as an attempt to explain a phenomenon or answer a question (instead of simply labeling a diagram).

Any particularly effective elements of their models that helped you understand their thinking (whether or not their thinking is accurate, the way they organize their models is as important as the accuracy of what they represent.

INVESTIGATE LESSON SNAPSHOT

INVESTIGATE LESSON SNAPSHOT

Lesson 14: How should we evaluate trade-offs when considering different solutions?

BIG IDEA | The design of a food system, like any human system, requires consideration of several criteria, and decisions to prioritize certain criteria over others (trade-offs) may be needed; local solutions need to account for local ecological resources and constraints (one-size-fits-all approaches may not work well in all systems).

Routine |

Part |

Time |

Summary |

Slide |

Materials |

|

1 |

5 min |

Students consider why certain solutions were chosen over other options. Students consider the several solutions presented in the previous lesson and begin to ask why those solutions may have been considered or implemented over others. Students begin to grapple with the idea of context for each solution and potential trade-offs for choosing one design solution over another. Purpose: to motivate students to think about why certain design solutions are chosen and how the criteria and constraints may be used to evaluate trade-offs. |

A |

Science notebooks |

|

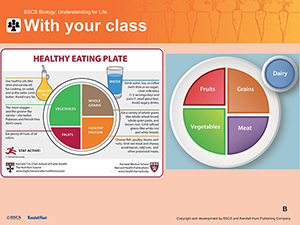

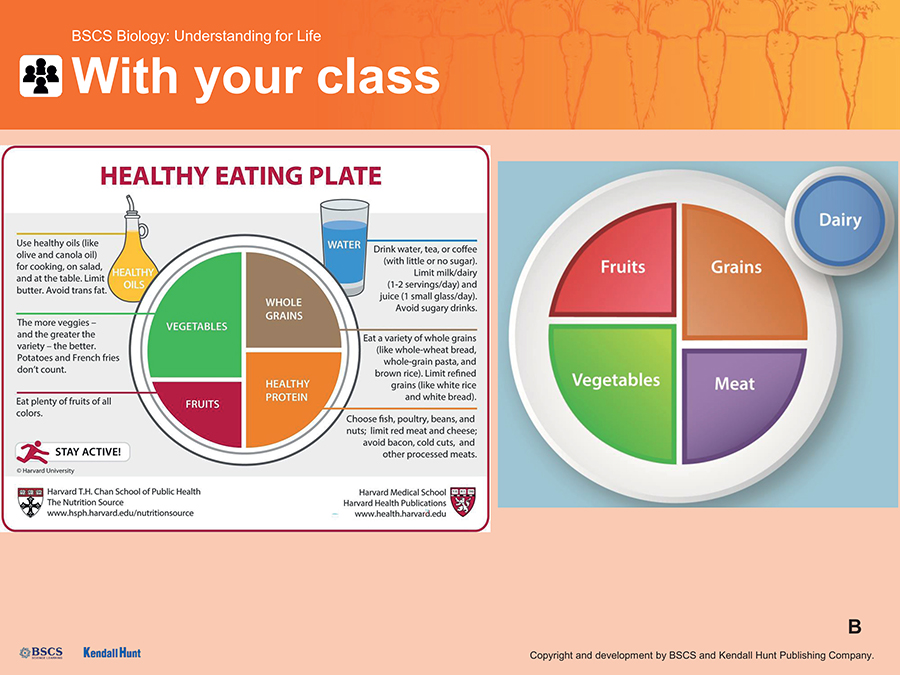

2 |

25 min |

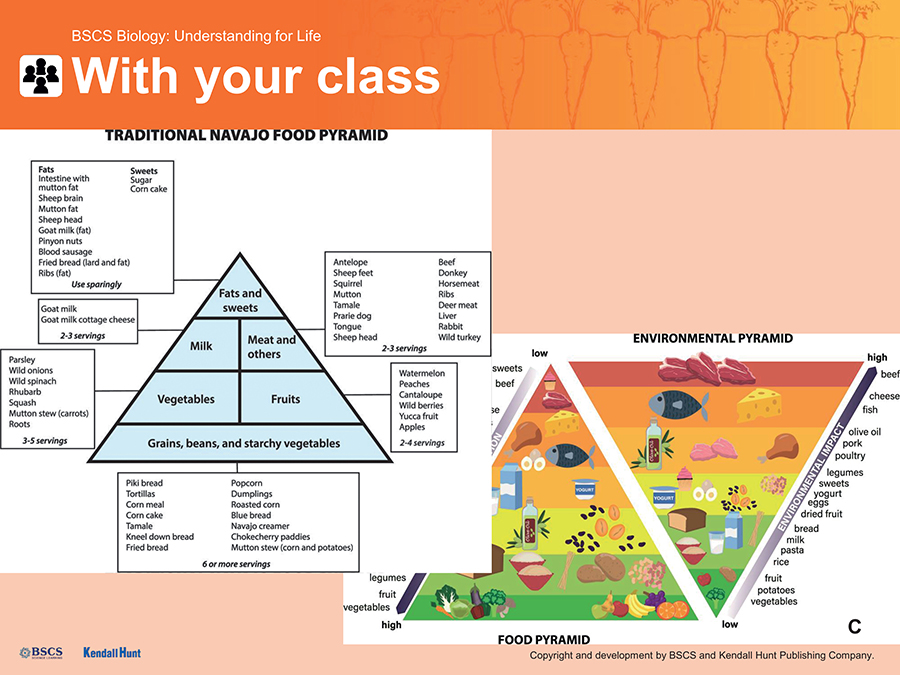

Consider influences of recommendations at a large population level. Students consider several different food pyramids designed to help people think about the types of foods they should consume and notice similarities and differences. Students read about and consider how and why certain foods may have been included as recommendations, and how each pyramid satisfies or doesn’t satisfy the criteria for a sustainable food system. Purpose: to support students to see that recommendations for what large populations of people should prioritize in their dietary patterns can be influenced by culture, economics, and scientific studies, and that each recommendation has trade-offs. |

B–E |

Student Sheet 3.14.A: Examining Food Pyramids Student Sheet 3.14.B: Criteria Venn Diagram Video: Esther Norton: Who influences what you eat? Student Sheet 3.14.F: Who Influences What You Eat Video Transcript |

3 |

20 min |

Consider influences at an individual level. Students think back to the meal planning activity from the Anchor Lesson, and look at labels for a single food item from the pantry that emphasizes different characteristics/qualities of that food and read about those characteristics. Students anonymously rank the order in which they would buy each item and justify their choice using both scientific ideas (e.g., ideas about nutrition and resources use) and non-science-related ideas (e.g., cultural norms, economics). Students also grapple with constraints and define the term. Purpose: to support students to see that individual people with knowledge of nutrition and natural resource use may make different choices and these choices may be influenced by that scientific knowledge but also by culture, religion, economics, and aesthetics. To support students to understand and define the concept of constraint. |

F–G |

||

Suggested class period break End of Day 1 |

|||||

|

4 |

5 min |

Students analyze data from their choices. Students realize that even in their own classroom community there are going to be different priorities for different people that are justifiable. Students notice that decisions about design solutions at different levels of the food system (e.g., educational materials to impact the US population food choices, and individual food choices for a meal for an event) will be subject to influences and bias. Purpose: to support students to notice that decisions made about a design solution require the consideration of both science and non-science ideas and the weighing of trade-offs. |

||

5 |

20 min |

Read about community solutions. Students return to the cases they read about in Lessons 12 and 13 and consider why the solution designers made the choices they did and consider what the trade-offs of those choices might be, and how the stakeholders and their biases may have played a role in the design decisions. Purpose: to provide examples of justifications for changes to food systems at different points in the system and at different scales and encourage students to consider stakeholders and biases that are involved in design decisions. |

P |

From Lesson 13: Student Sheet 3.13.F: Case Summaries |

|

|

6 |

10 min |

Look across all solutions. Students compare and contrast different solutions and notice all solutions are purposeful and address the problem but do so in different ways. Students recognize that all solutions are similar in that they can be justified both with scientific ideas and social understanding of community needs. Students compare a one-size-fits-all solution to the community solution. Purpose: to support students to understand that local solutions need to account for local ecological resources and constraints allow students to have agency in a community-based approach and understand a one-size-fits-all approach may not work well in all systems. |

H–J |

|

10 min |

Students update their Model Trackers. Students add to and/or annotate their Model Trackers. Purpose: to support students to use their Model Trackers to show how we should evaluate trade-offs when examining design solutions. |

K–L |

Science notebooks |

||

|

7 |

5 min |

Students reflect on their learning Students consider how the process of evaluating different design solutions at several different levels of scale can inform how they could design effective solutions that improve food systems to better meet nutritional, environmental, and social criteria. Purpose: to motivate students to consider how the process of evaluation might be useful when designing solutions. |

||

Suggested class period break End of Day 2 |

|||||

LESSON MATERIALS

Per student

Science notebooks

Student Sheet 3.13.F: Case Summaries (from Lesson 13)

Student Sheet 3.14.F: Who Influences What You Eat Video Transcript

Per class

Computer with projector

Preparation

Test audio and projection for playing the video.

Make copies of student sheets.

Determine how you will group students in groups of 3–4.

Determine how you will group students in groups of 4–5, ideally with one student who is an expert on each case from Lesson 13 in each group; these can be the same groups as in the Lesson 13 jigsaw activity.

ADDITIONAL CONTENT BACKGROUND FOR THE TEACHER

This lesson allows students to consider the role of criteria, constraints, stakeholders, and biases in developing and evaluating design solutions. According to the NAEP Governing Board’s definition of Engineering Design, “Criteria are characteristics of a successful solution, such as the desired function or a particular level of efficiency. Constraints are limitations on the design, such as available funds, resources, or time.”

Both criteria and constraints become relevant when considering trade-offs in design decisions. Trade-offs occur when a specific criterion is prioritized over others or when a constraint limits the choices designers have for their solution. For every design decision engineers make there are consequences—something may be gained because of the decision while another thing is given up.

NAVIGATE

NAVIGATE

PURPOSE | To maintain coherence and continuity

Students reflect on their progress so far.

Display Slide A. Have students open their science notebooks to a new page and write the date and “Lesson 14.” Ask students to consider the cases they read about in Lesson 13 and consider why those solutions might have been implemented over others.

Attending to Students Ideas

As students are considering why certain solutions are implemented over others they may voice that they think that it is because there is a single right solution that can be found for every problem. At this point in the lesson, allow students to express their ideas without correcting their thinking. Later in the lesson they will have the opportunity to see that every solution has trade-offs, and there are multiple solutions that can be equally as effective within a community.

Students co-construct the lesson question and consider what to investigate.

Based on what they learned in Lesson 13, ask students what they think might be important to help them understand why certain solutions were chosen over other options. Using their language, capture a question that is similar to: “How should we evaluate trade-offs when considering different solutions?” and write the question down either on a whiteboard or some public space. Have students record the lesson question on the page they started for Lesson 14 in their science notebooks.

Ask students to consider what they could investigate to begin to answer their lesson question. Remind students that they have just read about solutions within communities and that it might be helpful to consider trade-offs of solutions for different sizes and types of populations.

Attending to Student Ideas

Students may have other ideas about what will be important to investigate, or what they are most interested in investigating. Validate those other ideas as interesting but attempt to focus students on needing to know what might influence decisions to pursue different solutions and the trade-offs that accompany the decisions made. Other ideas they have can be added to the Driving Question Board in the form of questions they want answers for.

GATHER EVIDENCE

GATHER EVIDENCE

PURPOSE | To plan and carry out evidence gathering tasks

Orient students to the context of a solution for a large population.

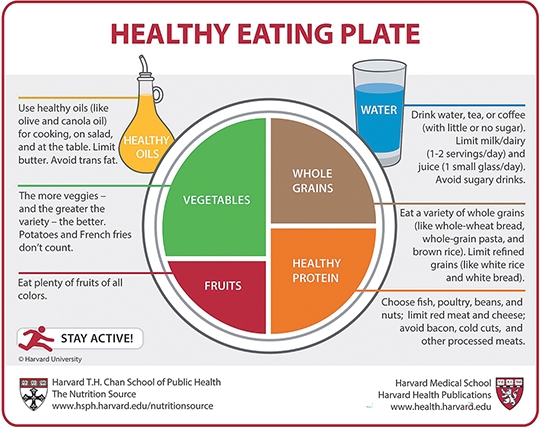

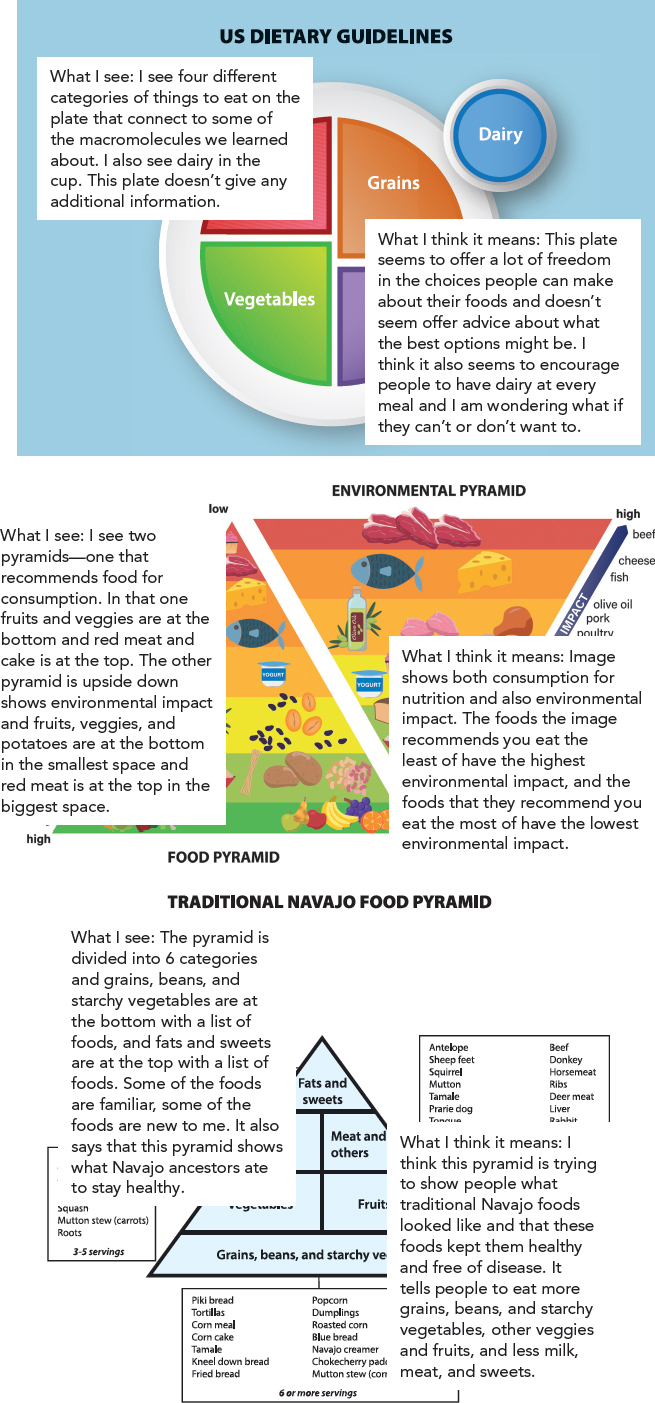

Display Slides B–C. Remind students that some of these food plates and pyramids they are seeing in the slides they have seen previously in the Anchor Lesson and others are brand new. Ask students to consider what all the food plates and pyramids are designed to do. Students will have more time to investigate each of the images in the next steps of the lesson. This first discussion is designed to surface ideas about what the images could be used for and how they connect to solutions to improve food systems.

|

X

|

X

|

| Suggested prompts | Listen for student responses such as |

|---|---|

| What are each of these food plates and pyramids designed to do? | It looks like each one is designed to help people know what and how to eat. |

| How do the images connect to the idea of solutions for improving food systems? | If they are designed to help people know what and how to eat they could influence the food system by increasing the consumption of some things over others. |

| Who is the audience for these images? | It depends on the image. Some of them look like they are for all the people in the United States. Others look like they might be made for specific groups of people (e.g., specific groups of Indigenous Peoples). |

| Are all the images the same? Why or why not? | No, they are all different. Some are plates, and some are pyramids. They have some similar groups mentioned, like meats, grains, etc. but where they are on the pyramid and what kinds of things are included are different. |

Invite students to examine the food plates and pyramids more closely to look for trade-offs.

Remind students that throughout Lesson 13 they looked at possible solutions for improving food systems for communities, businesses, and groups of people. Explain to students these food plates and pyramids are similar in that they are designed to educate people on food choices and therefore could potentially impact food systems. Distribute Student Sheet 3.14.A: Examining Food Pyramids.

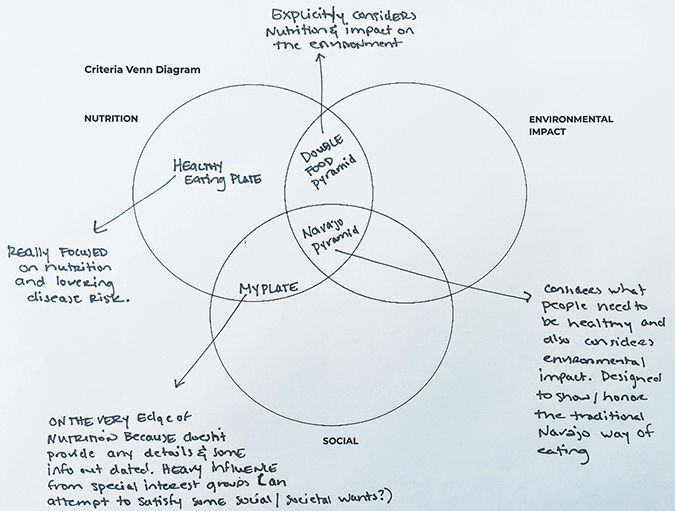

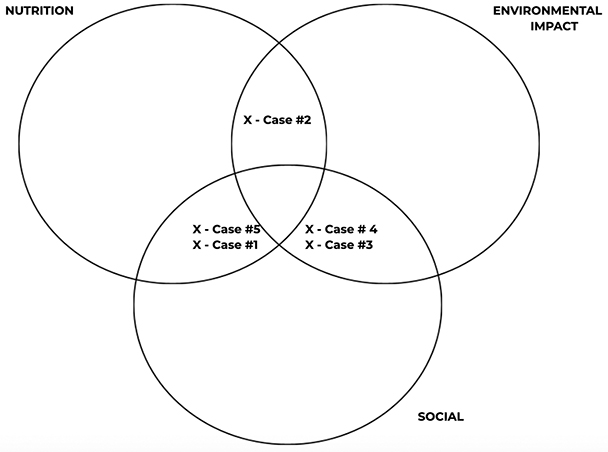

Divide students into groups of 3 or 4 and tell them they are going to have a chance to look more closely at each image, read about how it was designed, and compare each image to the criteria they developed for their design solution in Lesson 12. Capitalize on students noticing that there are some differences in the plates and pyramids and ask students if they think these differences may be related to prioritizing certain design criteria over others. Ask students how they might keep track of what criteria each food plate and pyramid addresses.

| Suggested prompts | Listen for student responses such as |

|---|---|

| Do you think some of the differences in the images come from prioritizing certain criteria over others? Why or why not? |

|

| As we analyze each image, how can we keep track of which criteria each one targets? | We could make a list of which criteria each image addresses and then compare them. |

| What if an image targets two or more of the criteria equally? | We could use something like a Venn diagram to show that the pyramid targets two or more things at once. |

Students may or may not come up with using a Venn diagram as a way to keep track of which criteria each image is targeting. If they do not, you might choose to introduce Student Sheet 3.14.B: Criteria Venn Diagram as a way to keep track of these ideas. If students do offer a Venn diagram as a possible way to keep track you may have them make their own version of Student Sheet 3.14.B.

Students use the I2 strategy and close reading protocol to examine the images and accompanying text.

Display Slide D. Prompt students to think about strategies they know that will help them note features and make sense of information when looking at visual displays (e.g., the I2 strategy).

Have students use the I2 strategy first to analyze and interpret the different images. Review that students will write What I see statements to identify what they see on each image. Then they will write What it means statements for each identify statement.

Samples of student statements.

Formative Assessment Opportunity

Reading students’ identify and interpret statements on the images is a good way to assess how well your students understand the I2 strategy, as well as their proficiency for using what they see and their scientific knowledge about nutrition as evidence for making statements about what the image is trying to convey to consumers.

This assessment opportunity can be informal, in that you may simply provide verbal feedback to students as you circulate to review their responses. You can also compile example responses you see as you check in with students. If you are not able to provide feedback to each student, encourage students to self-assess their use of the strategy.

The class sets a purpose for reading.

After students have examined the images, ask students to read the text that accompanies each image to gain more insight. Students should use the Science Close Read Protocol and set a purpose for their reading. We are investigating how we should evaluate trade-offs when considering different solutions, and we developed specific criteria in Lesson 12 to help us consider whether a food system or design solution was sustainable. Encourage students to read the information about each image and use the criteria to consider the areas of focus for each image.

Students consider trade-offs.

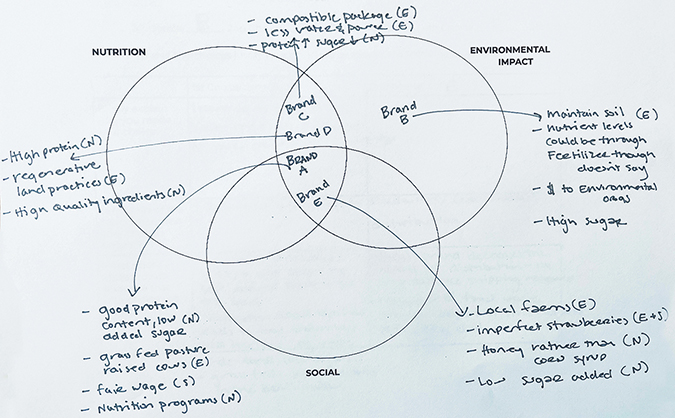

Once students have had a chance to analyze and read about each image, ask students to use a Venn diagram to show the criteria that each image seems to be targeting. Press students to justify each image’s placement on the Venn diagram using evidence from the images or justification from the text.

An example of how students might show which criteria each image is targeting and their justification is below:

Ask a few groups to elaborate on their choices and justifications. Also ask students to consider the trade-offs the creators may have made in their design.

| Suggested prompts | Listen for student responses such as |

|---|---|

| Explain why you put the USDA MyPlate where you did. |

|

| Do any of the images seem to prioritize set of criteria over others? What happens when one criteria is prioritized? |

|

| Does this only happen when one set of criteria is prioritized over others? Why or why not? | No, I think trade-offs could happen even if they are prioritizing all the criteria. In order to highlight all the criteria in some way that may mean you can’t be as specific. For example, the Navajo pyramid design seems to have considered nutritional, environmental, and social criteria but it was hard for us to see that in the image and we learned that from the text. |

Students earn the word trade-off.

Draw attention to the idea that for each design solution, the designers had to make choices about what to prioritize more in the design and what to prioritize less. These decisions typically result in trade-offs: something is gained in the design, while something else is given up. Put the term “trade-off” on the “words we’ve earned” Word Wall.

Students consider stakeholders and biases that play a role in the design.

Display Slide E. Inform students that they will watch a video to gain further insight into a Navajo perspective. This particular video is an interview with Esther Norton, a Diné (Navajo) knowledge keeper.

Distribute Student Sheet 3.14.F: Who Influences What You Eat Video Transcript. Play the video Who influences what you eat? Remind students that Esther is speaking as an individual and does not speak on behalf of all Indigenous Peoples.

Ask students to consider the stakeholders involved in food pyramids and plates, and the biases that may have played a role in the construction of these images.

| Are there any biases you see that may have played a role in what criteria got prioritized? |

|

| How do these biases and stakeholders end up impacting the food system? |

|

Attending to Equity

To support the unique culture and perspectives that each Indigenous student brings into your classroom you may want to reemphasize that “Indigenous” is a broad term comprising over 574 federally recognized American Indian and Alaska Native tribes (nations), and more than 200 unrecognized; each one is uniquely connected to their own land base, with their own language, culture, and way of life.

Be mindful also of not asking (or allowing peers to ask) Indigenous students to speak “for” their nation or culture either. You may welcome any volunteered contributions or connections students may make to this speaker, but avoid asking individual students to speak on the topic on the basis of their identity.

Developing the Practices: Designing Solutions

As students consider different food pyramids and food plates they evaluate them as a solution designed to influence people’s food consumption using their knowledge of nutritional, environmental impact, and social implications.

Ask students to consider if grappling with trade-offs, biases, and considering stakeholders only happens when making decisions for a population level solution.

Display Slide F. Remind students they had determined these images were all designed to influence food consumption for populations of people (the population of the United States, the Navajo population, etc.). Ask students if the same tensions would exist in the decision-making process for solutions at different levels of scale, for example, the community, or the individual.

Students choose between yogurt brands.

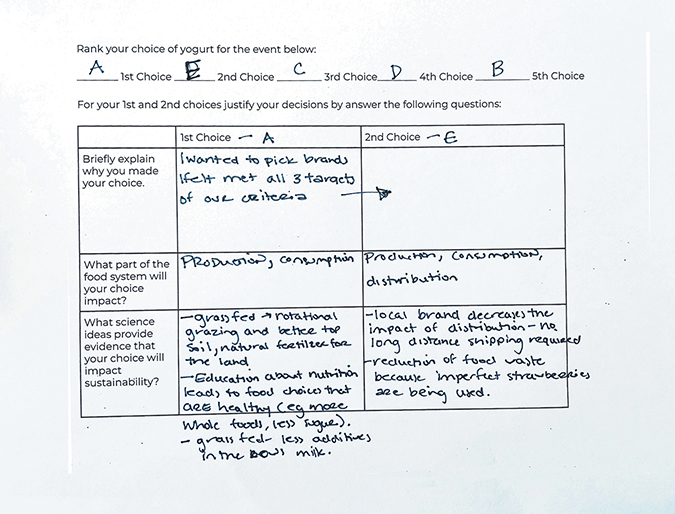

Display Slide G. Remind students of the experience they had in the Anchor Lesson (Lesson 1) of this unit, choosing items for a meal for a special event in the community. Tell students the strawberry yogurt will be included as an option in the meal but now they have to decide which brand to choose. Distribute Student Sheet 3.14.C: Yogurt Choice. Have students read about each brand of yogurt and then use the Venn diagram on the student sheet to consider which criteria each brand is targeting. Then, ask students to rank and justify their choices.

Students should complete the rankings independently. They can discuss their ideas with a partner but the choices should be made individually. You might also prompt students to look back at their models for chapters 7 and 8 to help them list scientific ideas that can justify their choices. Students are likely to place the brands in slightly different places on the Venn diagram based on what parts of the brand description jump out at them and their own personal biases about what is most important for sustainable food systems. One potential student response is shown here:

Collect student responses.

Once students have had a chance to rank and justify their choices, collect students’ responses and tell them you will compile their choices so we can see the distribution of the class.

Developing the Practices: Designing Solutions

As students consider different yogurt brands they could choose to include in a community meal they evaluate them as a solution designed to improve a local food system at the level of human consumption using their knowledge of nutritional, environmental impact, and social implications.

SUGGESTED CLASS PERIOD BREAK

End of Day 1

GATHER EVIDENCE

GATHER EVIDENCE

PURPOSE | To plan and carry out evidence gathering tasks

Display class yogurt choice data.

Redistribute student copies of Student Sheet 3.14.C: Yogurt Choice, and allow students to see how their individual choices compared to the choices their classmates made. Ask a few students to share their justifications for their choice.

| Suggested prompt | Listen for student responses such as |

|---|---|

| Why did you make the choice you did? |

|

Students consider the role of individual biases and trade-offs when making decisions.

After a few students have shared their choices and their justification, ask students to consider how their own lived experiences and personal biases may have impacted their choice. For example, if a student feels strongly about the treatment of animals or fair working wages, that may have impacted the choice they made. Having these biases may also have caused them to look past some of the other criteria or be willing to give in those areas. Remind students that we all have biases. Our own biases and lived experiences directly impact the decisions we make on a daily basis, and will directly impact any design solutions they come up with themselves.

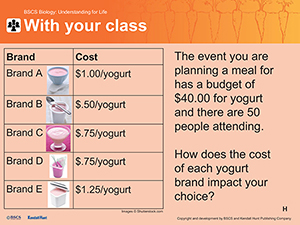

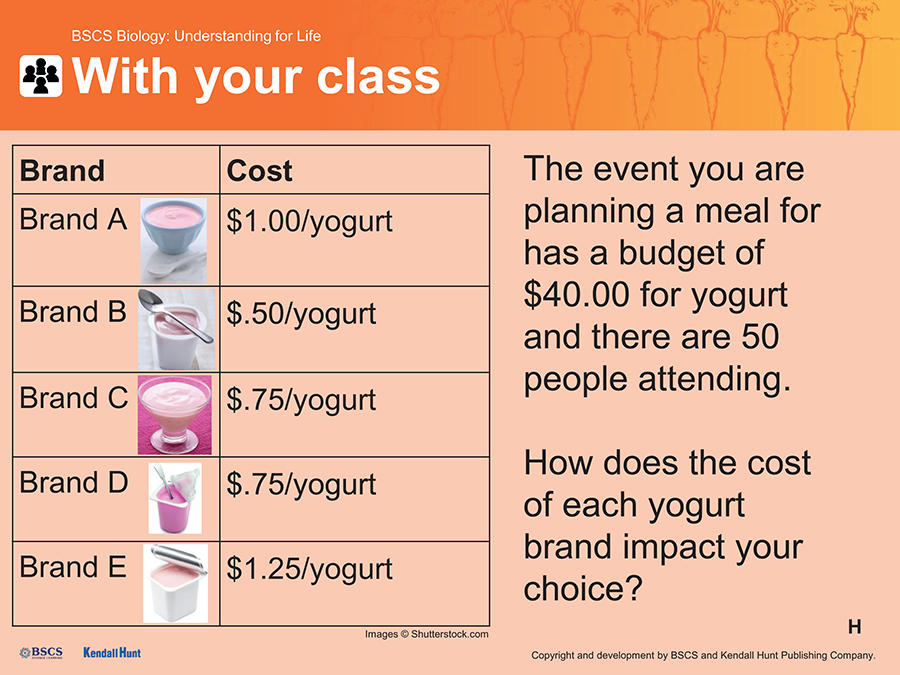

Highlight for students that the options they were given did not allow them to consider two important factors usually included in decisions about purchasing a product and consuming it: cost and taste. Ask students to individually consider how cost and taste would impact their priorities for criteria being met.

Attending to Equity

The cost of food items impacts different students in different ways. Some students in the classroom may never have had to make decisions based on the cost of items, whereas for others the cost will likely be the number one factor in determining which option they would choose. Inequities in terms of access and availability of food exist. Some students may want to share about their experience and others may not. Encourage all students to have empathy and to listen to their classmates’ experiences, should students choose to share.

Students consider a constraint in their choice.

Display Slide H. Ask students to consider the information on the slide, and determine how the cost of each brand of yogurt would impact their choice.

| Suggested prompt | Listen for student responses such as |

|---|---|

| How does the budget of the event and the cost of each yogurt brand impact your choice? |

|

Students consider the difference between criteria and constraints.

Ask students to compare the experiences of choosing the yogurt without a budget in mind versus with a budget in mind.

| Suggested prompt | Listen for student responses such as |

|---|---|

| How was making a choice within a budget different from making a choice without a budget? |

|

Students earn the word constraint.

Draw attention to the ideas that working with the budget limited the amount of choice the students would have, and staying within the budget was a criterion they had to satisfy, whereas how to prioritize the other criteria was not. Tell students that this difference that they are noticing is an important difference to consider. Criteria are the things the design needs to target to be successful or have impact. In a design problem, a limitation or restriction that the designers have little choice about or control over is referred to as a constraint. Put the term “constraint” on the “words we’ve earned” Word Wall.

Students consider the role of stakeholders, constraints, and trade-offs in design decisions.

Tell students they have now had the chance to see how stakeholders and biases can impact priorities and trade-offs at two different scales of decision-making: (1) decision-making for a population with the food pyramids and plates and (2) decision-making at the individual level of picking which yogurt brand to serve at a community meal. Tell students now they will have the chance to read more about the cases they considered in Lessons 12 and 13 and learn about why each person or group of people made the choices they did.

Ask students what might be helpful to keep track of when learning about why design solution decisions were made.

| Suggested prompt | Listen for student responses such as |

|---|---|

| Based on what we learned and experienced when looking at decisions made for a population level design solution and an individual choice level, what should we keep track of while learning more about the cases? |

|

Students may or may not bring up all of these key points of things to keep track of as they are learning about the cases. If these ideas don’t surface, use the students’ experiences examining the food pyramids and plates to remind them of specific things that might be important to consider and keep track of (e.g., the special interest groups likely having a role in what was highlighted in the USDA MyPlate as important things to consume daily).

Students learn more about the cases.

Make sure students’ charts summarizing the design solutions and science ideas from Lesson 13 are hung around the room in accessible locations for students to look at them when/if needed. Divide students into groups of 5 from the jigsaw activity in Lesson 13 to ensure there is one student who is an expert on every case in every group. Distribute Student Sheet 3.14.D: The “Why” Behind the Design and Student Sheet 3.14.E: Keeping Track of the Cases. As students work together to understand the justification of the designers, the stakeholders involved in each solution, and the biases that may have played a role in the choices that were made, circulate and ask questions to probe student thinking. Even though students considered the criteria for each case and the stakeholders involved in Lesson 13, ask students to think again about these categories while considering the new information they have about each case. Encourage students to use strategies that may be helpful to better understand the text (e.g., close reading protocol).

| Case | What criteria did the designers consider? | Who are the stakeholders involved? | What trade-offs are there if the designers prioritized certain criteria over others? | List any possible sources of bias that may have influenced the designer’s decisions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 IndigiKitchen |

Social–cultural needs Nutritional–decrease damage | Communities of Indigenous Peoples– specifically Cherokee | The designer doesn’t really talk about environmental criteria as a priority but does talk about using foods produced from sustainable methods. So it seems the criteria are important but just not specifically addressed with this solution. | The designer is heavily influenced by her culture but acknowledges that and that’s an important part of her solution. |

| 2 Briarwood Elementary |

Environmental–food waste Nutritional–health promoting | Students and families in the community of Briarwood Elementary. The school– won’t need to buy as much food if less is wasted. | The designers don’t really talk about social criteria in connection to the types of food being offered. However, in the design solution it did talk about making sure students had a variety of options–it’s just unclear how inclusive those were. | The designers seem to prioritize the environmental criteria over the others–could be related to teachers wanting students to learn about environmental impact of choices. |

| 3 Straus Family Creamery |

Social–animal treatment Environmental–land, water, technology | Straus family, rural communities, American farmers | The designer doesn’t really talk about nutritional criteria as being important. We think the nutritional content of the company’s product likely matters but doesn’t seem to be a consideration for the design solution. | Since it is a dairy farm the owners want to see dairy farming continue to exist because it is their means of life and that may cause them to be biased in their ideas of what solutions could work. |

| 4 Woodson High School |

Social–food access/availability Environmental–land use | Students and families in the community of Woodson High School, local food pantries | The designers seemed to prioritize social and environmental criteria–they were growing fruits and vegetables that are nutritionally health promoting but they didn’t talk specifically about that criteria being a part of the solution design. | The designers seem to prioritize the environmental criteria over the others–could be related to teachers wanting students to learn about environmental impact of choices during a time when there was community hardship. |

| 5 GrowNYC |

Social–food access/ availability Nutritional–health promoting/harm reducing | Farmers who sell at the markets, people who use SNAP benefits, the city of New York | The designers seem to prioritize both social and nutritional criteria. We know that the food is being grown and sold directly by farmers (likely on smaller farms) so this design could also be targeting some environmental criteria but we would need more information to determine that– we have no idea what the farming practices are. | The designers are aiming to keep people in the city so having that goal may influence the solution. |

An example of student responses for Student Sheet 3.14.E.

Student responses may differ regarding trade-offs and placement of each case on the Venn diagram. Rather than working toward consensus, use different responses as a way to foster discussion among groups of students, and highlight the importance of sometimes needing more information to really determine if a solution targets the design criteria or not.

Developing the Practices: Designing Solutions

As students consider different community-focused design solutions they evaluate them as a potential solution to improve a food system to be more sustainable using their knowledge of nutritional, environmental impact, and social implications.

GENERATE AN EXPLANATION

GENERATE AN EXPLANATION

PURPOSE | To build understanding from evidence

Students look across all solutions.

Display Slide I. After students have had a chance to look more closely at the designers’ justification for each solution, ask students to look across all five cases and compare and contrast them.

| Suggested prompts | Listen for student responses such as |

|---|---|

| What was different about each solution and the justification provided by the designers? |

|

| What is similar about each solution and the justification provided by designers? |

|

| Were there any constraints mentioned in any of the cases? If not, could you imagine constraints that might have impacted their design? |

|

| You have said all the solutions met all or some of the criteria we listed for change to create a more sustainable food system. Would any of these solutions then have worked in any of these environments? |

|

| Do you think one of these solutions is better than the others? |

|

Developing the Crosscutting Concepts: Systems and System Models

Food systems are designed to provide food for populations of people. As students consider different design solutions for specific aspects of a food system they understand that the design is specific to the needs of those implementing it. Each unique design within a community meets a specific set of criteria deemed most appropriate for the community the solution is serving.

Students compare the community solutions to the population level and individual level solutions.

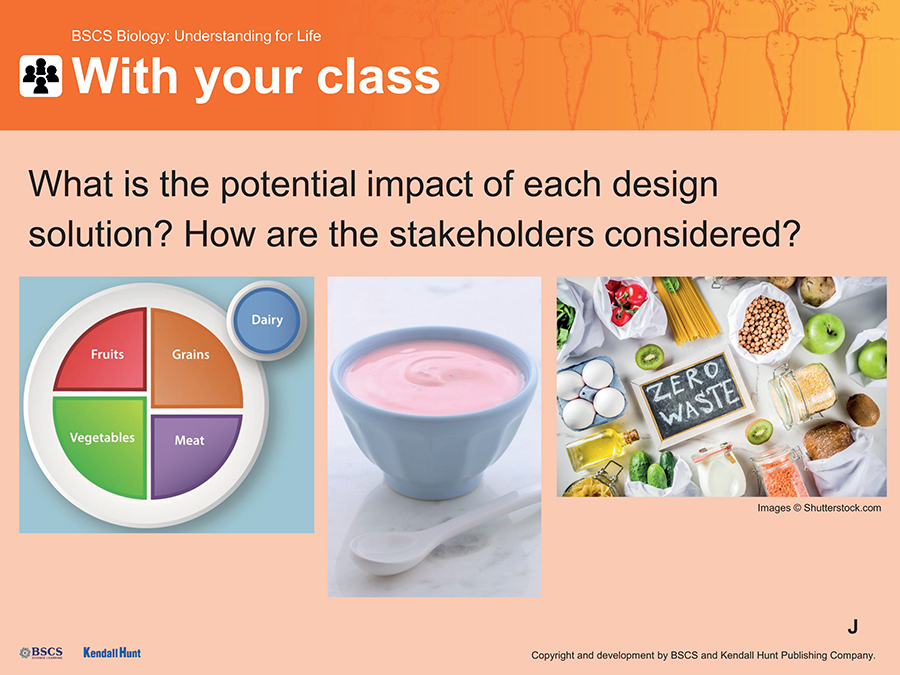

Display Slide J. After students had looked across the five case studies, ask them to reconsider the other solutions we looked at earlier in the lesson. Remind students that in this lesson we looked at several different design solutions, first at the population level, then at the individual level, then at the community level. Have students consider what they notice about the impact of the solution at each level.

| Suggested prompts | Listen for student responses such as |

|---|---|

| Population level impact? Consideration of stakeholders? |

|

Individual choice level? Consideration of stakeholders? |

|

The community level? Consideration of stakeholders? |

|

Students are likely to see that decisions made at all three levels of scale (population, individual, community) are likely to have trade-offs with respect to possible impact. Draw out student ideas regarding the importance of the design decision being responsive to local needs and resources, as this realization may help them define who their design solution is for and why in the unit’s Culminating Task.

Developing the Practices: Engaging in Argument from Evidence

Students compare and evaluate different community design solutions for sustainable food systems in light of their scientific understanding, justifications provided by the solution designers, trade-offs, and potential biases involved when deciding on and implementing a solution.

Developing the Crosscutting Concepts: Scale, Proportion, and Quantity

When considering design solutions for different numbers of people (large population versus community versus individual) students understand that the proposed solution may change depending on the population the food system is designed to serve. In addition, students consider the importance of community support for a design solution and the significance of how well the solution may work is dependent on how many people within the community the solution impacts.

Students examine the process of evaluation.

Ask a student to remind the class of the lesson question: How should we evaluate trade-offs when considering different solutions? Display Slide K. Through the lesson, students have been working to evaluate different design solutions, both in respect to each other and also at different levels of scale. Support students to acknowledge the process they used to evaluate each.

| Suggested prompt | Listen for student responses such as |

|---|---|

| We considered several different solutions. How did we evaluate them? |

|

Students record the ideas they have figured out from the investigation in their Model Trackers.

Display Slide L. Prompt students to return to the Model Tracker in the front of their notebooks they have been adding to. Have them start an entry for Lesson 14 on the next fresh page, and record the lesson number, question, and the ideas we have figured out.

Have students think about important ideas we have figured out and then work individually to draw a model in the last column that represents a general model of how we evaluate trade-offs when considering different solutions.

Students use the Model Tracker Self-Assessment and Feedback Tool to refine their representations.

Remind students to consider their checklist criteria, review their models, and make any modifications they feel appropriate.

Remind students they also have feedback from you on their chapter 7 and 8 models to take into consideration.

Collect science notebooks for a formative assessment.

After class, review each student’s Model Tracker entries for this chapter using the Model Tracker Formative Assessment Tool as an available online resource. Enter individual feedback into that student’s Model Tracker Self-Assessment and Feedback Tool (attached to the very front page of the notebooks).

Formative Assessment Opportunity

Examine the Model Tracker entries for Lessons 12, 13, and 14 in student notebooks. The Model Tracker Formative Assessment Tool provides guidance on what to look for in student Model Trackers across all three of the Investigate lessons for this chapter in the form of a checklist. As you work through the checklist keep in mind what you are looking for.

Also keep in mind that you are not looking for neatness or for accuracy in the Model Tracker. The models students draw here are a description of their growing conceptual understanding and as such they may be inaccurate in some details of components, interactions, or explanations of phenomena.

In the appropriate space in each student’s Model Tracker Self-Assessment and Feedback Tool in the front of their science notebooks, provide feedback to students regarding the models in their Model Tracker for Lessons 12–14. Give students feedback on:

Any missing, or extraneous components.

Whether or not they have used the model as an attempt to explain a phenomenon or answer a question (instead of simply labeling a diagram).

Any particularly effective elements of their models that helped you understand their thinking (whether or not their thinking is accurate, the way they organize their models is as important as the accuracy of what they represent. This is why the feedback section has separate spaces for feedback on content and modeling).

This feedback will help students improve their practice of modeling and support continued growth in their conceptual understanding.

NAVIGATE

NAVIGATE

PURPOSE | To maintain coherence and continuity

Students reflect on how their learning can be used to help them think about designing food systems.

Have students consider how the process of evaluating design solutions at different levels of scale could inform the process of design.

| Suggested prompts | Listen for student responses such as |

|---|---|

| How could we use what we have learned from evaluating design solutions to inform future food system designs? | We could use a similar process of looking at stakeholders, examining biases, and using considerations. |

| What else might we want to know before we would propose a solution for a more sustainable food system? |

|

SUGGESTED CLASS PERIOD BREAK

End of Day 2

REFERENCES

“Native Health.” Indigikitchen. https://www.indigikitchen.com. (Student Sheet 3.14.D: The “Why” Behind the Design)

U.S. Green Building Council. “Case Study: Briarwood Elementary.” 2019. https://www.usgbc.org/sites/default/files/Briarwood%20Elementary%20Case%20Study%20January2020.pdf. (Student Sheet 3.14.D: The “Why” Behind the Design)

Straus Family Creamery. “Climate + Farm: Innovating for Tomorrow.” https://www.strausfamilycreamery.com/mission-practices/climate-farm. (Student Sheet 3.14.D: The “Why” Behind the Design)

Office of Communications and Community Relations. “Woodson Students Farm Vegetables on School Grounds for Fairfax Families In Need.” Fairfax County Public Schools. June 8, 2021. https://www.fcps.edu/blog/woodson-students-farm-vegetables-school-grounds-fairfax-families-need. (Student Sheet 3.14.D: The “Why” Behind the Design)

Owens, Nora, and Kelly Verel. “SNAP/EBT at Your Farmers Market: Seven Steps to Success.” Project for Public Places and Wholesome Wave. July, 2010. https://s3.amazonaws.com/aws-website-ppsimages-na05y/pdf/SNAP_EBT_Book.pdf. (Student Sheet 3.14.D: The “Why” Behind the Design)

Harvard Health Publications. The Nutrition Source, Department of Nutrition. Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health. www.thenutritionsource.org and www.health.harvard.edu. (Student Sheet 3.14.A: Examining Food Pyramids)

Ruini, Luca Fernando, Roberto Ciati, Carlo Alberto Pratesi, Massimo Marino, Ludovica Principato, and Eleonora Vannuzzi. “Working Toward Healthy and Sustainable Diets: The ‘Double Pyramid Model’ Developed by the Barilla Center for Food and Nutrition to Raise Awareness About the Environmental and Nutritional Impact of Foods.” Frontiers in Nutrition 2 (2015): 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2015.00009. (Student Sheet 3.14.A: Examining Food Pyramids)